Lupus vulgaris of the popliteal fossa: A delayed diagnosis

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D39md2k9jvMain Content

Lupus vulgaris of the popliteal fossa: A delayed diagnosis

Ilknur Kivanc Altunay MD1, Semra Kayaoglu MD2, Tugba Rezan Ekmekci MD1, Safiye Kutlu MD1, Esra Saygin Arpag MD3

Dermatology Online Journal 13 (3): 12

1. Dermatology Department, Sisli Etfal Teaching and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey2. Family Medicine Department, Sisli Etfal Teaching and Research Hospital

3. Silivri State Hospital , specialty in Dermatology

Abstract

Lupus vulgaris (LV) is the most common form of cutaneous tuberculosis. It commonly presents on the head and neck regions. The diagnosis may be difficult when LV occurs at unexpected regions or in unusual clinical forms. Sometimes special stains for the organism and mycobacterial cultures may be negative. Nevertheless, it is usually possible to reach the correct diagnosis of LV using clinical and histopathological findings. But at times, a therapeutic trial with antitubercular agents may be required.

Clinical synopsis

A 58-year-old man with a more than 1 year history of a persistent, ulcerated plaque of the right popliteal space was referred to our dermatology clinic. His first physician had prescribed various antibiotics, macrolides and cephalosporins, but these therapies were ineffective. He was later referred to a dermatologist. The dermatologist had made a presumptive clinical diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum after the patient refused laboratory tests and cultures. Although the ulceration improved and the plaque partially resolved at first, 2 months prior to being seen in our clinic, the ulceration again began to enlarge.

|

| Figure 1 |

|---|

Dermatological examination revealed an irregular 10.7 by 7cm plaque with an erythematous, violaceous, elevated border in the popliteal area; two small ulcerations that exhibited fresh granulation tissue were visible. There was a sclerotic region with a lighter color in the middle of the plaque (Fig. 1).

All biochemical and hematological laboratory investigations were normal except for increased sedimentation rate (65mm/h) and monocytosis (16.9 %, N:1.7-9.3) in the CBC. Chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. Tuberculin test (PPD) was positive with a 27 mm induration. Direct microscopy and cultures from the lesion, sputum and urine for bacteria, fungi, atypical mycobacteria, and mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT) were all negative.

|

| Figure 2 |

|---|

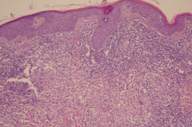

Punch biopsies were taken from the elevated edge, the middle area of the lesion and also from the ulceration. Histopathologically, granulomatous patterns including multinuclear giant cells (Langhans-type giant cells), epithelioid histiocytes with additional capillary proliferation, and heavy mononuclear cell infiltration in the dermis were detected (Fig. 2). Acid-fast staining for MT, atypical mycobacteria, and PAS staining for fungi were all negative.

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

The patient was diagnosed presumptively with lupus vulgaris (LV). Antitubercular therapy (isoniazide 300mg/d, pyrazinamide 1500 mg/d, rifampicin 600 mg/d, and ethambutol 1500 mg/d) was administered as a therapeutic trial for 6 weeks and a total of 6 months of treatment was planned. The lesion began resolving within the first few weeks with flattening of the elevated and hyperkeratotic border and healing of the ulcerations. Finally, just hyperpigmentation and an atrophic scar remained (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Atypical localizations and atypical clinical presentations of LV may occur and lead to difficulty in diagnosis and treatment [1, 2, 3, 4]. The clinical presentation of cutaneous tuberculosis may vary depending upon host immunity, infection route and previous exposure [5, 6]. Unexpected areas such as the trunk, extremities, periocular, and perianal regions might be involved instead of the conventional regions such as the head and neck, especially the nose, the cheek, and the ears [3, 4, 7]. The characteristic morphological patterns are papular, nodular, and tumid. Atypical clinical forms, such as cellulitis, folliculitis, lichen simplex chronicus, sporotrichoid, framboesiform, lichenoid gangrenous, ulcero-vegetant and tumor-like types may occur [1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. These clinical forms of LV emerge sporadically and often lead to misdiagnosis and delayed or incorrect therapy. In our case, the unusual site on the leg, sharp edges of ulcers, and scarring simulated pyoderma gangrenosum. The absence of response to antibiotic therapy, the patient's refusal of minimally invasive testing, and the early response to corticosteroids produced difficulties in the diagnosis.

Upon presentation to our clinic, the differential diagnosis included LV and atypical mycobacterial diseases, especially Myobacterium marinum (MM) and Myobacterium ulcerans (MU). However, MM infections are more commonly seen on the hands as single or multiple papules or nodules that may ulcerate later or present in a sporotrichoid pattern [12]. As for MU infections, they mostly occur in subequatorial regions, are clinically more aggressive, and have a different histopathology. Myobacterium ulcerans infections would be unlikely in our geographical location. Other mycobacterial skin infections are generally associated with internal involvement and with immunosuppression; these did not exist in our case. Pyoderma gangrenosum was also excluded on the basis of histopathology and the progression in spite of high dose corticosteroid treatment. The diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis is normally made by clinical and histopathological data. Laboratory methods such as PPD test, culture of bacilli, PCR, and MycoDot serology tests are supportive of the diagnosis [13, 14]. A therapeutic trial with antitubercular drugs lasting 4-6 weeks for diagnosis is indicated in difficult cases [15, 16]. Our patient was difficult to diagnose for two reasons. The first was the atypical presentation of LV. The second was the inconclusive laboratory analyses except for PPD and pathology report. The rapid response to ATT therapeutic trial confirmed the correct diagnosis.

References

1. Khandpur S, Reddy BSN. Lupus vulgaris :unusual presentations over the face J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Nov;17(6):706-10. PubMed2. Wozniacka A, Schwartz RA, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Borun M, Arkuszewska C. Lupus vulgaris :report of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 2005 Apr;44(4):299-301. PubMed

3. Senol M, Ozcan A, Mizrak B, Turgut AC, Karaca S, Kocer H. A case of lupus vulgaris with unusual location. J Dermatol. 2003 Jul;30(7):566-9. PubMed

4. Ceylan C, Gerceker B, Ozdemir F, Kazandi A. Delayed diagnosis in a case of lupus vulgaris with unusual localization . J Dermatol. 2004 Jan;31(1):56-9. PubMed

5. Kivanc-Altunay I, Baysal Z, Ekmekci TR, Koslu A. The incidence of cutaneous tuberculosis in the patients with organ tuberculosis. Int J Dermatol. 2003 Mar;42(3):197-200. PubMed

6. Hamada M, Urabe K, Moroi Y, Miyazaki M, Furue M. Epidemiology of cutaneous tuberculosis in Japan: a retrospective study from 1906 to 2002. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Oct;43(10):727-31. PubMed

7. Rekha A, Ravi A, Sundaram S, Prathiba D. An uncommon sighting--lupus vulgaris of the foot. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2003 Jun;2(2):96-8. PubMed

8. Bork K. Disseminated lichenoid form of lupus vulgaris. Hautarzt. 1985 Dec;36(12):694-6. PubMed

9. Podda M, Schofer H, Milbradt R. Lupus vulgaris vegetans by auto-inoculation in open pulmonary tuberculosis. Hautarzt. 1994 Jun;45(6):389-93. PubMed

10. Hruza GJ, Posnick RB, Weltman RE. Disseminated lupus vulgaris presenting as granulomatous folliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1989 Jul-Aug;28(6):388-92. PubMed

11. Brauninger W, Bork K, Hoede N. Tumor-like lupus vulgaris. Hautarzt. 1981 Jun;32(6):321-3. PubMed

12. Bartralot R, Garcia-Patos V, Sitjas D, Rodriguez-Cano L, Mollet J, Marti-Casabona N, Coll P, Castells A, Pujol RM. Clinical patterns of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Br J Dermatol. 2005 Apr;152(4):727-34. PubMed

13. Padmavathy LRL. Utility of Mycodot test in the diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol. 2003; 69: 428-9

14. Quiros E, Maroto MC, Bettinardi A, Gonzalez I, Piedrola G. Diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis in biopsy specimens by PCR and southern blotting. J Clin Pathol. 1996 Nov;49(11):889-91. PubMed

15. Pandhi D, Reddy BSN, Chowdhary S, Khurana N. Cutaneous tuberculosis in Indian children: the importance of screening for involment of internal organs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2004 ;18(5): 546-551. PubMed

16. Sehgal NV, Serdana K, Sehgal R, Sharma S. The use of anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) as a diagnostic tool in pediatric cutaneous tuberculosis. Int J Dermatol 2005;44(11) : 961- 3. PubMed

© 2007 Dermatology Online Journal