Severe cutaneous interface drug eruption associated with bendamustine

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D385n6c9jfMain Content

Severe cutaneous interface drug eruption associated with bendamustine

Habibollah S Alamdari BA1,3, Lauren Pinter-Brown MD2,3, David S Cassarino MD PhD4, Melvin W Chiu MD MPH1,3,5

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (7): 1

1. Division of Dermatology2. Division of Hematology and Oncology

3. Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, California

4. Department of Pathology, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, California

5. Dermatology Service, West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Los Angeles, California

Abstract

Bendamustine is an anti-neoplastic agent approved by the FDA in 2008 for use as monotherapy or in combination with other agents to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and progressed indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). In clinical trials and post-marketing safety reports administration of bendamustine with drugs that have known adverse reactions (i.e., allopurinol, rituximab) has been associated with rash, toxic skin reactions, and bullous exanthems. Here, we describe a patient with NHL who developed a severe cutaneous reaction associated with the administration of bendamustine. The severity of this drug eruption identifies an important adverse reaction with this drug and a potential cause for patient morbidity.

Introduction

Bendamustine is an intravenously-administered alkylating agent approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that has progressed despite treatment with rituximab or a rituximab-containing regimen. Rare cases of severe drug eruptions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) have been reported when bendamustine has been used with rituximab, allopurinol, and other medications with the potential for severe drug eruptions [1]. We report a case of a man with NHL who developed a severe cutaneous eruption with a histologic pattern of interface dermatitis while on bendamustine without simultaneous rituximab or allopurinol.

Case report

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Erythematous desquamating patches on the chest, arms, and abdomen Figure 2. Erythematous desquamating patches on the back | |

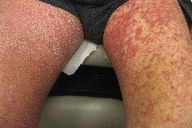

A 75-year-old male with grade 1-2 follicular B-cell lymphoma that had relapsed despite treatment with local irradiation, rituximab, combination fludarabine and rituximab, and cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP), presented with a pruritic desquamating erythematous skin eruption without full-thickness epidermal sloughing diffusely on his scalp, face, trunk, and extremities (Figures 1 through 4). There were no typical or atypical targetoid lesions. He also had tender erythematous macules on his upper palate without ulceration. The cutaneous and oral lesions began 5 days after his second dose of bendamustine, delivered at a dose of 90 milligrams per square meter (mg/m²) intravenously over 2 days. Three weeks earlier, he had received bendamustine 80 mg/m² intravenously over 2 days with allopurinol 300 mg by mouth daily for 5 days. His only other medications were valsartan for hypertension, docusate sodium for constipation, acetaminophen for osteoarthritis, and loratadine for allergic rhinitis. He had no fever or chills and no complaints of gastrointestinal upset or abdominal pain. His vital signs were normal and blood tests showed normal liver function and a blood count without eosinophilia.

|  |

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|---|

| Figure 3. Erythema and desquamation on the volar hands Figure 4. Erythematous desquamating patches on the thighs | |

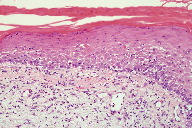

A punch biopsy taken from the right forearm revealed an interface dermatitis with marked basovacuolar alteration, numerous dyskeratotic keratinocytes, and exocytosis of small lymphocytes into the basilar half of the epidermis (Figure 5). There was also a mild superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered eosinophils and neutrophils. Given the histological and clinical findings, the diagnosis of severe drug eruption with interface dermatitis related to bendamustine was made. The patient was started on a 3-week prednisone taper beginning at 60 mg daily and his eruption showed slow improvement of over several weeks.

Discussion

Bendamustine has been shown to be effective in the treatment of NHL and CLL. Studies have shown bendamustine to be superior to chlorambucil therapy in treating CLL and effective in treating rituximab-refractory indolent NHL, with an overall response rate of 68 percent and 77 percent respectively [2, 3]. Cutaneous eruption has been reported in 8 percent of CLL patients on bendamustine and 16 percent of NHL patients on bendamustine, but National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Grade 3 or 4 rash has been reported in 3 percent of CLL patients and <1 percent in NHL patients. Rarely, SJS or TEN has been reported, usually when used in combination with medications such as rituximab or allopurinol [1].

Cutaneous reactions to drugs are common, affecting 2-3 percent of hospitalized patients [4, 5]. Drug eruptions begin in dependent areas and generalize symmetrically with red macules and papules forming a confluence that often spares the face; however, mucous membranes, palms, and soles may be involved. Pruritus is common and low-grade fever may or may not be present at the onset. Maculopapular or morbilliform eruptions can be indicators for more serious dermatologic reactions such as hypersensitivity syndrome, serum sickness, SJS, and TEN. The onset is normally within 2 weeks of starting a new drug and can be within days if the patient has been previously sensitized. Resolution normally occurs upon discontinuation of the drug, but resultant mucocutaneous scarring or end-organ dysfunction may be long-term sequelae [5, 6].

A review of 9 studies shows maculopapular eruptions accounting for up to 95 percent of drug-induced skin eruptions [7]. But these cutaneous eruptions can have a diverse pathology with an elusive diagnosis so it is important to have a histopathological reference for clinical evaluation and diagnosis. A recent retrospective histological study covering 5 years of diagnosed drug eruptions found that 53 percent of cases exhibited an interface dermatitis and 80 percent of cases exhibited a perivascular and interstitial pattern of dermal infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils [8]. Another study identified more histological features including sparse vacuolar interface dermatitis, scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the dermal-epidermal junction, and sparse superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate [9].

Regarding the lymphocytic interface dermatitis, there are both cell-poor and cell-rich classifications that aid in identifying the disease process by the character and intensity of the infiltrate that is present along the dermal-epidermal junction. Drug eruptions, erythema multiforme, and autoimmune connective tissue disease are prototypes of cell-poor interface dermatitis, whereas cell-rich dermatitis is typified by lichenoid disorders. The lymphocytes present along the interface can point to an immune based pathology. Typical examples include a Type 2 reaction caused by autoantibodies targeting the basement membrane or a Type 4 reaction causing hypersensitivity and cytotoxicity [10].

Recently, the pathophysiology of drug eruptions has become clearer. A review of immunohistological studies has found that cytotoxic granule proteins (such as perforin and granzyme B) from activated CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, are of vital importance in the generation of the histological features of drug-induced exanthems. There is evidence that when these proteins are released from cytotoxic CD4+ T-cells there is a greater association with keratinocyte damage in maculopapular eruptions versus when they are released from cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells (when there is more severe tissue damage resulting in bullous exanthems). There is also evidence for the heterogeneous upregulation of both type 1 and type 2 cytokines. In combination with chemokines like eotaxin (CCL-11), the type 2 cytokine, interleukin-5, is able to account for the typical tissue eosinophilia seen in these eruptions because these inflammatory markers are known to be vital in regulating the growth and activation of eosinophils [11]. However, there are no absolute findings for any drug eruption, so correlation between clinical and histological findings are still the foundations for diagnosis.

There is difficulty when one must factor in the effects of chemotherapeutic agents. In associated cutaneous reactions the pathogenesis for most of these types of eruptions is speculative and is usually categorized as direct toxicity, hypersensitivity reaction, or non-immunological drug eruption. Aside from cutaneous eruptions, a patient’s reaction to this class of drugs can be just as diverse as the pathogenesis. Alopecia, hyperpigmentation, photosensitivity, acral erythema, and nail dystrophies can all be induced by chemotherapeutic drugs [12]. Although some drugs have been studied extensively, the burgeoning numbers of new therapies, like bendamustine, make it particularly vital to fill the void of large scale studies that can reliably describe the drugs’ cutaneous reactions and their mechanisms. A 2008 study attempting to summarize the literature up to this point highlighted the lack of information on this subject [12].

Conclusion

Drug eruptions related to chemotherapeutic agents are common. Our patient had a severe cutaneous drug eruption with interface dermatitis that resolved after stopping bendamustine and starting prednisone. Because of their physical and histological presentation, it is easier to diagnose drug eruptions than it is to pinpoint their precise mechanism, especially in the case of chemotherapeutic agents. It is important for physicians to be aware of the complexity of patients on chemotherapy and the possible cutaneous reactions that can arise.

References

1. Treanda [package insert]. Frazer, PA: Cephalon, Inc.; 2008.2. Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Phase III randomized study of bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:4378-4384. [PubMed]

3. Friedberg JW, Cohen P, Chen L, et al. Bendamustine in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent and transformed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Results from a phase II multicenter, single-agent study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:204-210. [PubMed]

4. Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1272. [PubMed]

5. Stern RS, Shear NH. Cutaneous reactions to drugs and biological modifiers. In: Arndt KA, LeBoit PE, Robinson JK, Wintroub BU, eds, Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery: An Integrated Program in Dermatology. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1996: 412.

6. Habif TP. Drug Eruptions: Clinical Patterns and Most Frequently Causal Drugs. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2004: Chapter 14.

7. Bigby M. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:765-770. [PubMed]

8. Gerson D, Sriganeshan V, Alexis JB. Cutaneous drug eruptions: a 5-year experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:995-999. [PubMed]

9. Crowson AN, Brown TJ, Magro CM. Progress in the understanding of the pathology and pathogenesis of cutaneous drug eruptions. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:407-428. [PubMed]

10. Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC. Interface dermatitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:652-666. [PubMed]

11. Brönnimann M, Yawalkar N. Histopathology of drug-induced exanthems: is there a role in diagnosis of drug allergy? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:317-21. [PubMed]

12. Sanborn RE. Cutaneous reactions to chemotherapy: commonly seen, less described, little understood. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:103-119. [PubMed]

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal