Livedo racemosa, secondary to drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D38289g3rxMain Content

Livedo racemosa, secondary to drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus

Taylor DeFelice MD MPH, Phoebe Lu MD PhD, Aaron Loyd MD, Rishi Patel MD, Andrew G Franks Jr MD

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (11): 24

Department of Dermatology, New York University, New York, New YorkAbstract

We present a 40-year-old man with erythematous-to-violaceous, broken, reticulated patches on the upper chest, back, and extremities, which is consistent with livedo racemosa. The cutaneous findings appeared after an increase in dilantin dose and subsequently improved after a reduction in dilantin dose. Furthermore, antinuclear antibodies and antihistone antibodies were detected. We therefore believe that the livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of a drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus. We review the distinctive features of livedo racemosa as well as its associations with several disorders. Although there are no effective treatments for livedo racemosa, patients often are placed on low-dose aspirin and counseled to avoid smoking in an effort to protect against their increased risk of stroke and arterial thrombosis.

History

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

A 40-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic at Bellevue Hospital Center in July, 2009, for evaluation of a mildly pruritic eruption. Medical history included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, right middle cerebral arterty infarct, right central retinal artery occlusion, myocardial infarction, mitral regurgitation, chronic renal insufficiency, and generalized seizures, which began in 2004. Medications included dilantin, metoprolol, simvastatin, coumadin, and calcium. The last seizure occured in June, 2009, after which the dilantin dose was increased from 200 mg to 400 mg daily. The eruption began shortly thereafter. On presentation, multiple, erythematous, reticulated patches were present diffusely over his trunk and extremities. The patient denied photosensitivity, chest or abdominal pain, joint pains, fever, malaise, oral sores, Raynaud phenomenon, or decreased urination. The patient reported no known drug allergies. He smokes four to five cigarettes a day and lives at the Bellevue shelter.

Two skin biopsies were performed. The dilantin dose was subsequently lowered to 300 mg daily with improvement of the eruption. Currently the patient is on 200 mg of dilantin at bedtime and levetiracetam 500 mg twice daily has been added. The plan is to continue to taper the dilantin if the patient remains seizure-free.

Physical examination

Partially-blanching, erythematous-to-violaceous, broken, reticulated patches were present on the upper chest, back, upper arms, thighs, and lower legs.

Laboratory data

The hemoglobin was 10.9 gm/dl, platelet count 127 x 109/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 65 mm/hr, C-reactive protein 37 mg/L, blood urea nitrogen 32 mg/dl, creatinine 2.7 mg/dL, antinuclear antibody titer 1:320 with a nucleolar pattern, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody 18 IU/ml, and antihistone antibody positive at 1.7. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, rheumatoid factor, hepatitis B antigen, and hepatitis C antibody were negative. A computed tomography scan of the head showed a chronic right middle cerebral infract. A renal ultrasound indicated intrinsic renal disease.

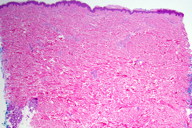

Histopathology

At the dermal-subcutaneous junction, there is a focal, perivascular, infiltrate of lymphocytes. No definitive fibrin deposition is identified.

Comment

Drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may resemble a milder version of idiopathic SLE. There is no gender predilection, and the affected population is usually older. Although cutaneous involvement is observed less frequently in drug-induced SLE than it is in idiopathic SLE, when skin findings do occur in this setting, the clinical and histopathologic features are not well-characterized and are often non-specific (e.g., livedo reticularis, purpura, erythema nodosum, and photosensitivy). In contrast, the classic cutaneous features of idiopathic SLE are usually absent (e.g., malar rash, discoid lesions, mucosal ulcers, alopecia, and Raynaud phenomenon). Systemic symptoms, such as fever and arthralgia may be present, but central nervous system and renal involvement are rare [1]. Antinuclear antibody and antihistone antibodies almost always are positive and their titers gradually decline with resolution of the disease [2]. Mild cytopenia and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate also are typical laboratory findings.

The mechanism of drug-induced SLE is not clear. In some cases, the implicated drugs may act as haptens and/or antigens and drive an immune response that is converted to autoimmunity [3]. Management of drug-induced SLE is based on the withdrawal of the offending drug and the use of topical and/or systemic glucocorticoids. Other immunosuppressive agents are reserved for refractory cases, which actually may be cases of preexisting SLE exacerbated by the implicated medication. The cutaneous findings usually abate in a period of weeks although complete resolution may take several months [1].

The term livedo racemosa was first introduced in 1907. It is characterized by a violaceous-to-erythematous, netlike pattern, which is similar to that of livedo reticularis but differs by its more generalized location (not only limbs but also trunk and/or buttocks); irregular, broken, circular, segmented shapes; and histopathologic features. In the rheumatologic literature, the distinction is often not made and the term livedo racemosa rarely is used [4]. Livedo racemosa occurs in several disorders, which include antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), SLE with or without APS, essential thrombocytopenia, thromboangiitis obliterans, polycythemia vera, polyareritis nodosa, and livedoid vasculopathy. Notably, it is the characteristic cutaneous sign of Sneddon syndrome.

The strong association between livedo reticularis and cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) in SLE patients has been reported frequently [5, 6]. One study found an association between livedo racemosa and cerebral or ocular ischemic arterial events, seizures, all arterial events, heart valve abnormalities, hypertension, and Raynaud phenomenon [7]. In a cohort of patients with APS there was an association between livedo racemosa and CVA, migraines, and epilepsy [8]. Livedo racemosa also has been linked to APS patients with renal artery stenosis [9] and arterial thrombosis [7]; the antiphospholipid antibodies interact with endothelial cells in a way that alters their function [9].

Widespread livedo racemosa associated with an ischemic CVA is the hallmark of Sneddon syndrome, which most commonly affects women before or during middle age; the first CVA usually occurring before age 45 [10, 11]. The eruption may be located on the limbs, trunk, buttocks, face, hands, or feet, with the trunk and/or buttocks involved in nearly all patients. The cutaneous findings are noted prior to the CVA in over 50 percent of cases and may precede the stroke by years. About 40 to 50 percent of patients with Sneddon syndrome have antiphospholipids [12] and one study found that this subgroup more frequently exhibits seizures, mitral regurgitation, and thrombocutopenia < 150 x 109/L [13].

Biopsy specimens of livedo racemosa often fail to yield diagnostic arterial lesions [4]. In order to detect the vascular pathology, the biopsy specimens should be of uninvolved skin at the center of a livedo racemosa area, and the biopsy size should be 1-2 cm; serial sections should be examined [14]. Sensitivity increases appreciably if more than one deep punch biopsy is taken from both red and white regions [15]. A stage-specific pattern has been described in which only small-to-medium-size arteries of the dermis-subcutis border are involved. The stages progress from a lymphohistiocytic attachment, to partial or complete occlusion of the lumen by lymphohistiocytic cells and fibrin, to proliferating subendothelial cells and dilated capillaries in the adventitia of the occluded vessel, to a final fibrosis and shrinkage of the affected vessels [14].

There is no effective treatment for livedo racemosa. Anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy does not preclude the appearance or spread of lesions. Low-dose aspirin often is prescribed in an effort to prevent strokes although its effectiveness has not been determined. Furthermore the potential benefits of clopidogrel, statins, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have not been established. Owing to the greater tendency of livedo racemosa patients to suffer a CVA and arterial thrombosis, risk factors for thrombosis and arterial wall lesions should be reduced, which include avoidance of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives and smoking [4].

References

1. Marzano AV, et al. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatologic aspects. Lupus 2009;18:935 [PubMed]2. Grossman L, Barland P. Histone reactivity of drug-induced antinuclear antibodies: a comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Arthritis Rheum 1981;24:927 [PubMed]

3. Mor A, et al. Drug-induced arthritic and connective tissue disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008;38:249 [PubMed]

4. Uthman IW, Khamashta MA. Livedo racemosa: a striking dermatological sign for the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol 2006;33:2379 [PubMed]

5. McHugh NJ, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies, livedo reticularis, and major cerebrovascular and renal disease in systemic lupus erythermatosus. Ann Rheum Dis 1988;47:110 [PubMed]

6. Baguley E, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies, livedo reticularis, and cerebrovascular accidents in SLE. Ann Rheum Dis 1988;47:702 [PubMed]

7. Frances C, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of the antiphospholipid syndrome: two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1785 [PubMed]

8. Toubi E, et al. Livedo reticularis is a marker for predicting multi-system thrombosis in antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:499 [PubMed]

9. Sangle SR, et al. Renal artery stenosis in the antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome and hypertension. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:999 [PubMed]

10. Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol 1965;77:180 [PubMed]

11. Frances C, Piette JC. The mystery of Sneddon syndrome: relationship with antiphospholipid syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2000;15:139 [PubMed]

12. Kraemer M, et al. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa: a literature review. J Neurol 2005;252:1155 [PubMed]

13. Frances C, et al. Sneddon syndrome with or without antiphospholipid antibodies: a comparative study in 46 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 199;78:209 [PubMed]

14. Zelger B, et al. Life history of cutaneous vascular lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol 1992;23:668 [PubMed]

15. Wohlrab J, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome: a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:285 [PubMed]

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal