Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D37v08f7q4Main Content

Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa

Carina Rizzo MD, Niroshana Anandasabapathy MD, Ruth F Walters MD, Karla Rosenman MD, Hideko Kamino MD, Steven Prystowsky MD,

Julie V Schaffer MD

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (10): 26

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityAbstract

A 47-year-old Vietnamese woman presented with dystrophic fingernails and toenails that had been present since infancy. She also had developed, in the third decade, pretibial pruritus with vesicle formation and progressive localized papules and scars. Multiple family members were similarly affected. Physical examination showed lichenoid papules that coalesced into large plaques that were studded with milia over the pretibial areas and 20 nail dystrophy. A biopsy specimen showed milia-like structures and dermal fibrosis. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa is a rare variant of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa that shows appreciable clinical overlap with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruginosa. Both disease subsets are characterized by the late age of onset, nail dystrophy, and predominantly pretibial pruritic lichenoid skin lesion; they are associated with glycine substitution mutations in COL7A1.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

History

A 47-year-old Vietnamese woman was referred to the Dermatology Clinic at Bellevue Hospital Center in January, 2008, for consideration of phototherapy for presumed refractory lichen planus. The patient presented with a complaint of dystrophic fingernails and toenails, which had been present since infancy. Vesicles that healed slowly with scars over the pretibial areas were occasionally noted in childhood. At the age of 27, after the birth of her first child, worsening of pretibial pruritus occurred. Since that time, pruritus has been most severe in the summer months. Scratching had resulted in the formation of vesicles, which healed with progressive, localized, papules, and scars. Treatment with topical emollients and glucocorticoids improved the pruritus but had no affect on the cutaneous lesions. There were multiple family members with similar nail and skin changes or with isolated nail dystrophy, which is depicted in the pedigree below. There was no family history of consanguinity.

A review of systems was otherwise unremarkable. The past medical history included a recent diagnosis of type II diabetes mellitus and prior treatment with isoniazid for asymptomatic pulmonary tuberculosis. Medications included metformin, a multivitamin, and aspirin.

Physical Examination

The patient was a generally well-appearing woman with violaceous, firm, lichenoid papules that coalesced into large plaques that were studded with milia over the bilateral pretibial areas. There were a few 3-to-5mm, lichenoid papules on the elbows. There were rare excoriations but no vesicles. Nikolsky's sign was negative. All 20 nails were rudimentary and dystrophic, with ridged atrophic plates and distal loss of the nails. The mucus membranes, hair, and teeth were normal.

Lab

Mutation analysis is being obtained to further characterize this patient's disease.

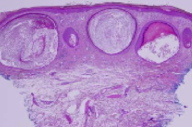

Histopathology

There is prominent, superficial, dermal fibrosis within which are multiple small cysts lined by keratinizing epithelium. The direct immunofluorescence pattern was nonspecific.

Comment

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) represents a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders that are characterized by defects in type VII collagen and sublamina densa blisters. Type VII collagen is encoded by a large and complex gene that is located on chromosome 3p21 [1]. Once synthesized, procollagen must be assembled into a homotrimer to form functional collagen. The inheritance and clinical expression of DEB depend on the nature and functional implications of individual underlying mutations, which impact different stages of the complex synthesis and assembly of anchoring fibrils. This accounts for both the myriad manifestations of disease and frequent clinical overlap among the various subtypes of DEB.

The rare pretibial variant of DEB was first described by Kuske in 1946 [2]. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa (PEB) has since been reported in several families of mostly Asian descent. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa is distinguished from other forms of DEB by a milder phenotype which is characterized by nail dystrophy, scars, and milia that are frequently associated with pruritic, lichenoid papules. The skin lesions preferentially affect the pretibial skin. Intact blisters rarely are observed. Although nail dystrophy presents in childhood, onset of skin lesions typically occurs after ten years of age [1, 3] and has been reported to occur as late as the fifth decade [1, 4]. Nail dystrophy may occur in the absence of other clinical manifestations of disease in family members as was demonstrated in our case and in several in previously reported pedigrees [5, 6]. Exacerbation has been described at puberty [7], with pregnancy [5], and with high heat and humidity [7], although no pathologic mechanism for these associations has yet been proposed. An increased incidence of cutaneous malignant conditions has not been described.

Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa shows appreciable clinical overlap with another rarely described DEB subset, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa (DEB-Pr). Several authors have suggested these conditions may represent the same disease [5, 7, 8]. Both are characterized by a later age of onset, nail dystrophy, and predominantly pretibial, pruritic, lichenoid skin lesions. Because of these features both conditions have been confused with inflammatory disorders, such as prurigo nodularis, lichen amyloidosis, dermatitis artefacta, and lichen planus (LP) [1, 4, 7, 8], as was the case with our patient who was originally referred for phototherapy of presumed LP.

As its name suggests, DEB-Pr is more specifically characterized by severe pruritus. Histopathologic features include a sparse, perivascular or lichenoid infiltrate. Clinical features include predominantly pretibial lichenoid papules and nodules although the skin lesions may be more widespread [4]. Pruritus has been known to occur with wound healing and has been described in association with many forms of EB. The more severe pruritus associated with DEB-Pr has been postulated to relate to underlying immune dysregulation; however, no association with atopy, IgE levels, or other systemic causes of pruritus have yet been found.

Inheritance of both PEB and DEB-Pr is autosomal dominant, although sporadic [5] and compound heterozygous [9] cases have been described. Mutational analysis of several pedigrees have shown glycine substitution mutations in COL7A1 in both diseases. The patients studied include a Taiwanese family [10] with PEB and three Japanese patients [11], two Chinese families [4, 5], and an Italian pedigree [6] with DEB-Pr. Because these substitution mutations may lead to subtle changes in the structure of collagen, ultrastructural studies of affected skin typically show absent or minor quantitative and structural alterations in anchoring fibrils [1, 5]. Single cases of splice site mutations [9] and small nucleotide deletions [6] have been reported in DEB-Pr patients, although such variability may be related to clinical overlap or to the challenge of reliably distinguishing the clinical subtypes of DEB.

Recent advances in the treatment of junctional EB by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells [12] and successful gene expression repair by spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing in EB simplex [13] promise to revolutionize the treatment of EB. However, until such interventions become available, clinical management remains limited. There have been case reports of the use of cyclosporine [14], thalidomide [15], and topical tacrolimus [16] for the treatment of pruritus associated with DEB-Pr. Some improvement in the cutaneous presentation may result from limiting damage due to excoriation. For now, prevention of trauma and local wound care remain the mainstays of treatment.

References

1. Naeyaert JM, et al. Genetic linkage between the collagen type VII gene COL7A1 and pretibial epidermolysis bullosa with lichenoid features. J Invest Dermatol 1995; 104: 803 PubMed2. Kuske H. Epidermolysis traumatic, regionar uber beiden tibiae zur athrophie fuhrend mit dominanter verenbung. Dermatological 1946; 91: 304

3. Soriano L, et al. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa. Int J Dermatol 1999; 38: 536 PubMed

4. Ee HL, et al. Clinical and molecular dilemmas in the diagnosis of familial epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: S77 PubMed

5. Lee JY, et al. A glycine-to-arginine substitution in the triple-helical domain of type VII collagen in a family with dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. J Invest Dermatol 1997; 108: 947 PubMed

6. Drera B, et al. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa in Italy: clinical and molecular characterization. Clin Genet 2006; 70: 339 PubMed

7. Bridges AG, Mutasim DF. Pretibial dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Cutis 1999; 63: 329 PubMed

8. Tang WYM, et al. Three Hong Kong Chinese cases of pretibial epidermolysis bullosa: a genodermatosis that can masquerade as an acquired inflammatory disease. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999; 24: 149 PubMed

9. Betts CM, et al. Pretibial dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: a recessively inherited COL7A1 splice site mutation affecting procollagen VII processing. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141: 833 PubMed

10. Christiano AM, et al. Pretibial epidermolysis bullosa: genetic linkage to COL7A1 and identification of a glycine-to-cysteine substitution in the triple-helical domain of type VII collagen. Hum Mol Genet 1995; 4: 1579 PubMed

11. Tamai K, et al. Particular mutations in exon 85 of type VII collagen gene induce severe itch: specific glycine substitutions for dominant forms of epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. J Invest Dermatol 1998; 110: 509

12. Mavilio F, et al. Correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells. Nat Med 2006; 12: 1397 PubMed

13. Wally V, et al. 5' trans-splicing repair of the PLEC1 gene. J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128: 568 PubMed

14. Yamasaki H, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa prurigonosa successfully controlled by oral cyclosporine. Br J Dermatol 1997; 137: 308 PubMed

15. Ozanic Bulic S, et al. thalidomide in the management of epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152: 1332 PubMed

16. Banky JP, et al. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa withtopical tacrolimus. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 794 PubMed

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal