Clinico histopathological correlation in leprosy

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D37t73h253Main Content

Clinico histopathological correlation in leprosy

K N Shivaswamy MBBS MD DNB, A L Shyamprasad MBBS MD, T K Sumathy MBBS MD MNAMS, C Ranganathan MBBS MD DD, Vidushi Agarwal

MBBS

Dermatology Online Journal 18 (9): 2

M S Ramaiah Medical Teaching Hospital Bangalore, Karnataka, IndiaAbstract

INTRODUCTION: Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by M. leprae, which presents in different clinico-pathological forms, depending upon the immune status of the host. Clinical classification gives recognition only to gross appearances of the lesions, whereas the parameters used for the histopathological classification are well defined, precise, and also take into account the immunological features. RESULTS: Of the 182 suspected cases of leprosy which were biopsied, the clinical diagnosis was TT in 32 (17.5%), BT in 70 (38.4%), BB in 5(2.7%), BL in 24 (13.1%), LL in 23 (12.6%), and indeterminate in 28(15.3%) cases. Of the 182 cases, which were biopsied, only 136 (74.7%) showed histological features consistent with any one type of leprosy. The overall clinicohistological correlation was 74.7 percent. A comparison of the histopathological pattern with that of clinical pattern revealed that the maximum correlation was seen with LL (84.2%), followed by BL (73.3%), BT (64.1%), TT (56%), BB, and IL (50%). CONCLUSION: Because there is some degree of overlap in different types of leprosy, especially the unstable forms, the correlation can be made more accurate by combining clinical and histopathological features.

Introduction

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by M. leprae. Leprosy expresses itself in different clinico-pathological forms depending on the immune status of the host [1, 2]. Diagnosis of leprosy is based on different clinical parameters, which involve detailed examination of skin lesions and peripheral nerves [3, 4]. A reliable diagnosis hinges around a good histopathological diagnosis and demonstration of bacilli in histopathological sections [5, 6]. Clinical classification gives recognition only to gross appearances of the lesions, whereas the parameters used for the histopathological classification are well defined, precise, and also take into account the immunological features. Because there are only a few studies regarding cliniohistological correlation, we undertook this study.

|  |

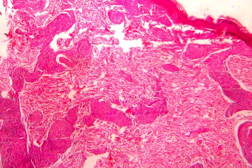

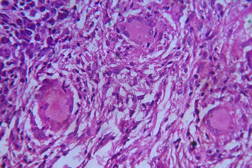

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Well-defined dry plaque with complete loss of sensation over back (TT). Figure 2. Well-defined plaque with satellite lesions over face (BT). | |

|  |

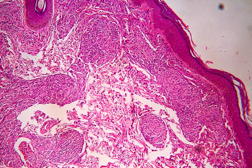

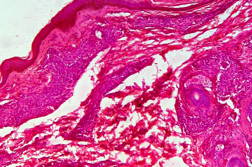

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|---|

| Figure 3. Multiple annular & punched out lesions over back (BB). Figure 4. Close up view of punched out lesions over Right buttock. | |

Aims and objectives

To study the clinicohistological correlation in leprosy.

Material and methods

We did a retrospective analysis of 182 clinically suspected cases of leprosy, which were biopsied over the past 10 years (between 2000 and 2009) after obtaining approval from the ethical committee at our institution. The clinical and histopathological diagnoses were correlated.

Results

Out of 182 cases, 125 were male and 57 female with a male to female ratio of 2.2:1. The age range was from 3 to 81 years. Of the 182 suspected cases of leprosy, which were biopsied, the clinical diagnosis was TT in 32 (17.5%), BT in 70 (38.4%), BB in 5 (2.7%), BL in 24 (13.1%), LL in 23 (12.6%), and indeterminate in 28 (15.3%) cases. Of the 182 cases, which were biopsied, only 136 (74.7%) showed histological features consistent with any one type of leprosy. The overall clinicohistological correlation was 74.7 percent. Comparing the histopathological pattern with that of clinical pattern, the maximum correlation was seen with LL (84.2%), followed by BL (73.3%), BT (64.1%), TT (56%), BB and IL (50%). (Table 1 and Table 2).

|  |

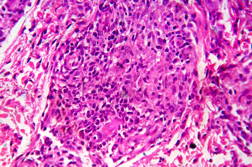

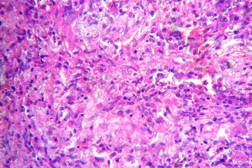

| Figure 19 | Figure 20 |

|---|---|

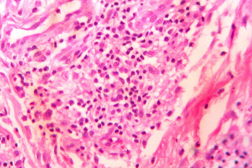

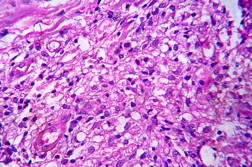

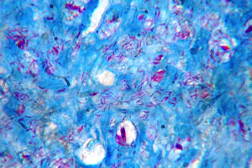

| Figure 19. High power view of the same showing infiltration of dermis by foamy macrophages (x40). Figure 20. Fite-Faraco stain showing foamy macrophages with numerous AFB (x100). | |

|

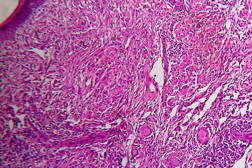

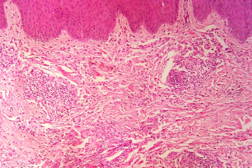

| Figure 21 |

|---|

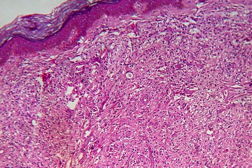

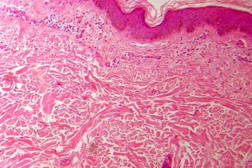

| Figure 21. Indeterminate leprosy showing patchy lymphocytic infiltrates in dermis and around appendages (x10). |

Discussion

In the present study, leprosy was classified clinically and histologically into different types based on the criteria devised by us (Table 3). Out of 182 clinically suspected cases of leprosy, biopsy showed features consistent with a particular subtype in 136, with an overall clinicohistological concordance of around 74.7 percent. This is in agreement with many other studies. The Ridley-Jopling classification is based on clinical, histopathological, and immunological features and is widely accepted by pathologists and leprologists. The discordance between clinical and histopathological diagnosis was noticed because the clinical diagnosis was based upon Ridley-Jopling classification, even when a histopathologial examination had not been done [7]. In our study the clinicohistological correlation was highest with LL (84.2%). The correlation accuracy in LL was followed by BL (73.3%), BT (64.1%), TT (56%), and 50 percent in BB and IL. This is on par with the results of the study conducted by Moorty et al, Sharma et al, and Jha and Karki [8, 9, 14]. Kar et al, Jarath et al, and Kalla et al in their study also showed a higher concordance with stable pole LL similar to our study. However, a high correlation was also noted with the other stable pole TT, which was not seen in our study [10, 11, 12] (Table 4). Correlation is supposed to be better at stable poles LL and TT probably related to clinical and histological stability of the disease. It was also observed in our study that the concordance was better in BT and BL rather than with TT, although they were unstable. This observation was also noted by Morthy et al and Sharma et al in their studies. In midborderline (BB) leprosy the correlation was low (50%). Even though it is on par with other studies like Moorthy et al, Kar et al, such a low concordance could not be explained since we had only 2 cases of BB. In our study IL showed concordance of about 47 percent, whereas other studies showed a concordance ranging from 20 percent by Moorty et al to 100 percent by Sharma et al [8, 9]. IL is an early and transitory stage of leprosy found in persons whose immunological status is yet to be determined and it may progress to one of the other determinate forms of the disease. The IL type appears to be problematic because of the non-specific histology of the lesion. The diagnosis of IL also depends on many factors such as nature and depth of the biopsy, the quality of sections, and number of sections examined, in both H& E and acid-fast staining. Our analysis showed nonspecific histological changes in 26 percent of clinically suspected cases of leprosy. However the studies by Singhi et al and Sharma et al have shown nonspecific histological changes at around 10 percent and 20 percent, respectively [9, 13].

Discordance between clinical and histopathological diagnosis can be explained on the basis that generally the diagnosis is made on clinical grounds alone, awaiting histopathological confirmation. It is possible that there is an individual observer bias also. Variation in different studies may be relate to different criteria used to select the cases: choosing the biopsy site, age of the lesion, morphology of the lesion, immunological and treatment status of the patient, retrospective versus prospective studies.

Conclusion

Because there is some degree of overlap in different types of leprosy, especially the unstable forms, the correlation can be made more accurate by combining clinical and histopathological features.

References

1. Panday AN, Tailor HJ. Clinocohistopathological correlation in leprosy. Ind J Dermatol Venerol Leprol 2008; 74: 174-76 [PubMed]2. Sengupta U. Leprosy: Immunology. In: Valia RG and ValiaAR (eds). IADVL Textbook and Atlas of Dermatology, 2nd edn. Mumbai. Bhalani Publishing House. 2001.pp. 1573.

3. Jopling WH, McDougall AC. Handbook of leprosy, 5th edition, Delhi, CBS Publishers and Distributors, 1999; 10-53.

4. Jopling WH, McDougall AC. Diagnostic Tests, In: Handbook of leprosy, 5th edn. CBS. 1999. P 60.

5. Lucus SB, Ridley DS. Use of histopathology in leprosy dignosis and research. Lep Rev 1989; 60: 257-62. [PubMed]

6. Harboe M. "Overview of host-parasite relations." In: Hastings RC, Opromolla DVA. Eds. Leprosy, 2nd edition, New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1994; 87-112.

7. Bhatia AS, Katoch K, Narayanan RB, et al. Clinical and histopathological correlation in the classification of leprosy. Int J Lepr 1993; 61:433-438. [PubMed]

8. Moorthy BN, Kumar P, Chatura KR, Chandrasekhar HR, Basavaraja PK. Histopathological correlation of skin biopsies in leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2001;67:299-301 [PubMed]

9. Sharma A, Sharma RK, Goswami KC, Bardwaj S. clinicohistopathological correlation in leprosy. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;10:120-3

10. Kar PK, Arora PN. Clinicopathological study of macular lesions in leprosy. Indian J Lepr 1994; 66:435-41.

11. Jerath VP, Desai SR. Diversities in clinical and histopathological classification of leprosy. Lepr India 1982; 54:130. [PubMed]

12. Kalla G, Salodkar A, Kachhawa D. Clinical and histopathological correlation in leprosy. Int J Lepr 2000;68:184-5 [PubMed]

13. Singhi MK, Kachhawa D, Ghiya BC. A retrospective study of clinico-histological correlation in leprosy. Ind J Pathol Microbiol 2003; 46: 47-8. [PubMed]

14. Jha R, Karki S. Limitations of Clinico-histopathological Correlation of Skin Biopsies in Leprosy. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2010;8(16):40-43 [PubMed]

© 2012 Dermatology Online Journal