Post-bone-marrow-transplant leukemia cutis

Main Content

Post-bone-marrow-transplant leukemia cutis

Fernando Pulgar MD, Dolores Vélez MD, Nuria Valdeolivas, Julio García MD, Alicia Cabrera, Laura Pericet MD, Lidia Trasobares

MD, Susana Medina MD, Mercedes García MD

Dermatology Online Journal 19 (2): 6

Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Madrid, SpainAbstract

Granulocytic sarcoma or chloroma is a tumor of immature cells from the granulocyte line that is generally associated with acute myeloid leukemia. The skin is one of the most affected organs. This lesion may complicate hematological dyscrasias, which is generally indicative of a poor prognosis. We present a case of a 51-year-old patient who was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia with a complex karyotype that debuted with a post-transplant cutaneous and hematological relapse, a very rare occurrence in the literature given that no extramedullary involvement was present prior to the transplant.

Introduction

Leukemia cutis is defined as cutaneous infiltration by neoplastic leukocytes (myeloid or lymphoid), resulting in clinically identifiable cutaneous lesions. When composed of neoplastic granulocytic precursors, leukemia cutis has been designated as myeloid sarcoma, granulocytic sarcoma, or chloroma.

Leukemia cutis has been described in patients with acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myeloproliferative disease, myelodysplastic sydromes, and myelodysplastic/lymphoproliferative diseases. In patients with chronic disease, skin involvement is associated with transformation into a blastic phase and suggests disease progression [1].

We present a case of a 51-year-old patient who was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia with a complex karyotype that debuted with a post-transplant cutaneous and hematological relapse, a very rare occurrence in the literature given that no extramedullary involvement was present prior to the transplant.

Case report

A 51-year-old female with an unremarkable history presented because of asthenia and anorexia. Following blood and bone marrow tests, the patient was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia with multilinear dysplasia, revealing a complex karyotype: 46XX (50%)/45XX del(5)(q13q33), -7, add(15)(q22), -18, +mar 50% and 30% blasts in the bone marrow. Molecular tests were only positive for WT-1. The patient received supportive and hypomethylating agent therapy that resulted in complete cytological and cytogenetic remission. Afterwards, the patient underwent a mini-haploidentical transplant with subsequent infusion of donor lymphocytes. Despite of this, the patient responded with early marrow (24% blasts in the bone marrow) and skin relapse.

|

| Figure 1 |

|---|

| Figure 1. Genital infiltration and ulceration |

The patient began to have asymptomatic plaques and ulcers in the genital area, which were present for two months before we were notified. Physical examination revealed significant induration and erythema of the vulva with erythematous and even tumor zones that also led to multiple bilateral ulcers measuring several centimeters in diameter. The ulcers had a fibrinous appearance and oval borders (Figure 1). There was continuity of the lesions to the inter-gluteal and perianal zone.

|  |

| Figure 2 | Figure 3 |

|---|---|

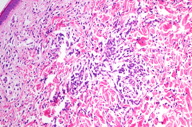

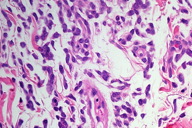

| Figure 2. At low-power magnification, the leukemic infiltrate shows diffuse/interstitial distribution with Grenz zone (x10). Figure 3. Dense blastic infiltrate in the dermis (x40). | |

|

| Figure 4 |

|---|

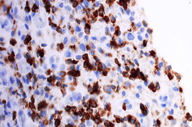

| Figure 4. The tumor cells of granulocytic sarcoma are strongly positive for myeloperoxidase (x40). |

A skin biopsy revealed the presence of a blastic infiltrate with a diffuse distribution involving the dermis and subcutis and without epidermotropism (Figure 2). Myeloblast and granulocytic precursors were the predominant cell components. The neoplastic cells were large, with relatively abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells also exhibited large nuclei with blastic (finely dispersed) chromatin and occasional small nucleoli (Figure 3). Mitotic figures and apoptosis were prominent. Macrophages and mature granulocytes were frequently seen. The tumor cells were strongly positive for myeloperoxidase (Figure 4) and negative for CD3, CD20 and TdT.

The patient had pancytopenia and was only receiving supportive and hypomethylating therapy. While awaiting evaluation for radiation therapy of the lesion, the patient expired within a few weeks.

Discussion

Patients with leukemia cutis may have single or multiple skin lesions [2]. The lesions are usually described as violaceous, red-brown, or hemorrhagic papules, nodules, and plaques of varying sizes. Erythematous papules and nodules are reported as the most common clinical presentation.

Legs are involved most commonly, followed by arms, back, chest, scalp, and face. Genital tract involvement is extremely rare. Leukemic infiltration tends to preferentially occur at sites of previous or concomitant inflammation [2]. A particular type of leukemia can produce different skin lesions during the course of the disease, even in the same patient.

The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is based on the morphologic pattern of skin infiltration, cytologic features, and most importantly, the imunophenotype of the tumor cells. Correlation with clinical data, bone marrow morphology, and peripherical blood findings is often helpful to confirm the diagnosis [3].

Based on histological findings alone, it is often impossible to assign lineage, which is essential for classification (myeloid, monocytic, or precursor B- or T-cell). The immunophenotyping is very important to generate a specific and clinically useful diagnosis.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and lysozyme are helpful in discriminating between myeloid and nonmyeloid cells. MPO is strongly positive in most neoplasms of granulocytic lineage. Lysozyme is a marker for granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages and is positive in myeloid and monocytic neoplasms but negative in lymphoid neoplasms.

In many cases, particularly in the absence of clinical information, leukemic deposits are readily confused with lymphoma, anaplastic carcinoma, melanoma, and histiocytic proliferations including Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Diagnosis is dependent upon the use of an adequate battery of immunohistochemistry and adequate clinical information.

It is difficult to give a precise incidence of leukemia cutis because the rate quoted in the literature is very variable and has not always depended upon histological confirmation. Overall, leukemia cutis occurs in 10-15 percent of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and less often in chronic myeloproliferative disease [4].

In our review there have only been described 50 cases [5] of myeloid sarcoma of the gynecologic tract reported with a history of acute myeloid leukemia. There are only two cases in which the vulva was primarily involved. Genitourinary extramedullary relapse was rare.

The time-to-relapse in the extramedullary sites was longer and patients were more likely to have had cronic graft versus host disease [5].

After a review of the literature [1-8], we have only found one article that reviews the occurrence of relapse1 in patient groups with acute myeloid leukemia [1]. Patients are divided into two post-bone-marrow-transplant groups; one group without extramedullary involvement (cutaneous) and another with involvement. That study concludes that the level of extramedullary relapse is greater in patients who already had extramedullary involvement before the transplant than in the group that developed extramedullary involvement after the transplant.

Conclusion

We present a case of a patient without previous extramedullary involvement who recurred with an early concomitant medullary and cutaneous relapse following transplant (which is extremely rare), resulting in spectacular clinical lesions and an unfortunate prognosis.

References

1. Michel G et al. Risk of extramedullary relapse following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. Bone marrow transplantation. 1997;20:107-112 [PubMed]2. Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, Vega F. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008 Jan;129(1):130-42. [PubMed]

3. Weedon D. Cutaneous infltrates: lymphomatous and leukemic. Skin Pathology. 2nd ed. New York, NY:Churchill Livingstone; 2002: 1118-1120

4. Agis H, Weltermann A, Fonatsch C, et al. A comparative study on demographic, hematological, and cytogenetic findings and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia with and without leukemia cutis. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:90-95 [PubMed]

5. Nazer A, Al-Badawi I, Chebbo W, Chaudhri N, El-Gohary G. Myeloid sarcoma of the vulva post-bone marrow transplant presenting as isolated extramedullary relapse in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2012;5(2):118-21. [PubMed]

6. de Arruda Câmara VM, Morais JC, Portugal R, da Silva Carneiro SC, Ramos-e-Silva M. Cutaneous granulocytic sarcoma in myelodysplastic syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 2008 Sep;35(9):876-9. [PubMed]

7. Vardiman JW et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009 Jul 30;114(5):937-51. [PubMed]

8. Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011 Oct 6;118(14):3785-93 [PubMed]

© 2013 Dermatology Online Journal