A rapidly progressing, fatal case of primary systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting as erythroderma - association with carbamazepine

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D336f5d2hmMain Content

A rapidly progressing, fatal case of primary systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting as erythroderma - association

with carbamazepine

Feroze Kaliyadan MD DNB1, Sanjoy Ray DNB2, Mary Kathleen Mathew3, Santosh Pai DNB3, L Sasikala MD DNB4, Rema Pai MD4

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (12): 5

1. Assistant Professor, Dept. of Dermatology. ferozkal@hotmail.com2. Asssitant Professor, Dept. of Internal Medicine

3. Resident, Dept. of Internal Medicine

4. Professor, Dept. of Internal Medicine

Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India

Abstract

A 73-year-old male patient admitted with erythroderma was diagnosed to have primary systemic Analpastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) positive, CD 30 positive, anaplastic large cell lymphoma. The patient's condition deteriorated rapidly during the period after the diagnosis was confirmed, with subsequent death before chemotherapy could be started. He had been started on carbamazepine, for diabetic neuropathy three months prior to the development of the skin lesions. Here we highlight the possibility of carbamazepine inducing anaplastic large cell lymphomas and the need for a high level of suspicion to make an early diagnosis allowing rapid appropriate treatment in such cases.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old male patient presented to us with a history of rapidly progressing, generalized and relatively asymptomatic, erythematous skin lesions with scaling of one-month duration. The patient also complained of increasing fatigue and weight loss over the last 2 months. The patient was a known diabetic, on oral anti-diabetic medications. Three months prior to the onset of skin lesions, he had been started on carbamazepine for diabetic neuropathy (from another hospital). The patient was also on long-term medication for hypertension and dyslipidemia. Other than carbamazepine, there was no history of any recent, new or changed medications.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Generalized lesions over abdomen Figure 2. Erythematous papules and plaques with scaling of the dorsum of hands | |

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

| Figure 3. Infiltrated lesions on ear lobes |

On examination - the patient's vital signs were stable. He was drowsy, but conscious and oriented. General examination was normal except for prominent bilateral pitting pedal edema. There was no significant lymphadenopathy. Erythematous papules and infiltrated plaques with scaling were seen in a generalized pettern, with relative sparing of scalp and soles (Figs. 1-3). There were no evident vesicles, erosions or ulcers. All mucosae were uninvolved. Respiratory system examination revealed reduced breath sounds over the right infra-scapular and infra-axillary areas. The rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable.

|

| Figure 4 |

|---|

| Figure 4. CT chest and abdomen showing multiple lymph nodes in mediastinal and abdomino-pelvic regions |

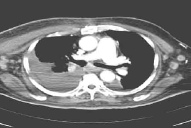

Clinically, the possibilities of a drug (carbamazepine)-induced erythroderma, erythroderma secondary to internal malignancy and a primary cutaneous lymphoma were considered. Carbamazepine was withheld and the patient was investigated further. Significant laboratory investigation findings included -a prominent leukocytosis (total count 25,800/mm³), hyponatremia (110 m.mol /l), and raised Lactate De- Hydrogenase (LDH) levels (1268.0 U/L, normal range 240 - 480). The renal function was normal; urine did not show any proteinuria and urine osmolality was within normal limits. Blood and urine cultures did not show any significant growth. Peripheral blood smear report showed- normocytic, normochromic red blood cells with leukocytosis. The platelets were normal in count and morphology. There was no evidence of any atypical cells. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsies were also normal. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) ELISA and Anti-Nuclear Antibody profile were negative. Chest radiography showed a right-sided pleural effusion. Pleural fluid showed an exudative picture and was negative for malignant cells. Gram stain and Acid Fast Bacillus (AFB) stain did not reveal organisms. Pleural fluid culture also did not show any growth. Contrast Computerized Tomography (CT) of the abdomen and thorax showed multiple lymphnodes in mediastinal and abdomino-pelvic regions (Fig. 4). There was no radiological evidence to suggest involvement of other specific organs.

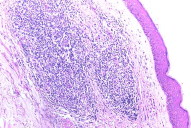

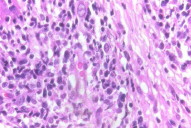

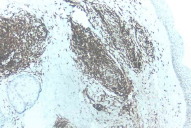

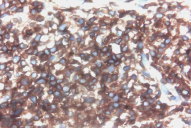

A skin biopsy taken from the infiltrated lesions revealed mild hyperkeratosis and flattened rete ridges with the dermis showing nodular infiltrates of monomorphic lymphocytes. In addition,large atypical lymphoid cells with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and scanty-to-moderate cytoplasm were present. These lymphoid collections were separated from the epidermis by a narrow zone of uninvolved dermis. There were no definite foci of Pautrier's micro-abscesses. However there was also no evidence of any significant dermal edema, spongiosis, extravasated erythrocytes, necrotic keratinocytes or epidermal eosinophilic infiltration. These negative findings are in concordance with the findings of Choi et al, who analyzed in detail the histological differences that distinguish a true lymphoma from a pseudolymphoma [1]. Immuno-histochemistry done on the skin sample showed the cells to be CD3 positive, CD 20 negative, with the large cells showing CD 30 positivity. The cells showed uniform strong positivity to ALK (Figs. 5-8).

|  |

| Figure 7 | Figure 8 |

|---|---|

| Figure 7. Immunostaining-lymphoid cells showing CD30 positivity (x10) Figure 8. Immunostaining-lymphoid cells showing ALK positivity | |

Based on the investigation findings a diagnosis of primary systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALK positive) was considered. The patient was already on conservative management with systemic antibiotics, measures for sodium correction, and topical corticosteroids and emollients. It was planned to start the patient on chemotherapy, but the general condition of the patient deteriorated very rapidly, progressing to multi-organ dysfunction and death within two weeks of admission. The renal function of the patient worsened in a very short period. A possibility of acute renal failure induced by tumor lysis or carbamazepine hypersensitivity (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms-DRESS) was considered because of the sudden renal function worsening associated with laboratory values suggesting hyperkalemia, hyperuricemia, and derangements in the phosphate and LDH levels (The calcium levels were however not significantly abnormal). The possibility of sepsis was ruled out by lack of organism growth on repeated blood and urine cultures.

Discussion

Carbamazepine has been frequently reported to cause hypersensitivity syndromes - with features of skin rashes, fever, lymphadenopathy, peripheral eosinophilia, acute renal failure, and hepatitis, among other features. The incidence of carbamazepine associated hypersensitivity reactions varies from one in thousand to one in ten thousand cases of carbamazepine administration [2, 3]. An immunological basis is postulated for these reactions, which probably accounts for the fact that the reactions often start after a period of 3-4 weeks. The mean duration of onset is 7 weeks (ranging from 3 to 24 weeks) [4, 5].

Carbamazepine is also known to cause pseudo-lymphomas / pseudo mycosis fungoides-like reactions [1, 6]. Cutaneous pseudo-lymphoma is a nonspecific term for a heterogeneous group of benign reactive T or B cell lymphoproliferative processes that simulate cutaneous lymphomas clinically or histologically [7, 8]. Carbamazepine-induced pseudolymphoma and carbamazepine induced drug hypersensitivity syndrome show considerable overlap with respect to general clinical features. Patients commonly present with fever, skin rash, facial edema, lymphadenopathy and hepatitis. Other features include myalgia, arthralgia, and pharyngitis. There have been isolated reports of true lymphomas associated with carbamazepine [5, 9], of which, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one report of carbamazepine-induced, CD30+, primary cutaneous, ALCL [5]. There are no reports of an ALK +, primary systemic ALCL associated with carbamazepine. Cutaneous biopsies may show features resembling mycosis fungoides (MF), such as epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes and Pautrier microabscesses. However, features favoring Pseudolymphoma over true lymphoma are the presence of marked spongiosis, necrotic keratinocytes and eosinophilic infiltrate in the epidermis, papillary dermal edema, extravasated erythrocytes, lymphocytes within the dermis larger than those in epidermis, and infiltration of various inflammatory cells including neutrophils [1]. Immune dysfunction is considered to be an underlying basis for carbmazepine-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, pseudolymphoma and possibly true lymphoma. In this context it is also interesting that carbamazepine has been reported to induce tumors in rats [10].

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) is a distinct category of large cell lymphoma characterized by an expression of the cytokine receptor CD30 on all or most neoplastic cells. On the basis of the morphologic, immunophenotypic, and clinical heterogeneity, several subtypes of ALCLs have been recognized, the most important ones being primary systemic ALCL, primary cutaneous ALCL (which belongs to the spectrum of CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders); and secondary ALCL [11]. The pathogenesis of systemic ALCL is linked to abnormal phosphorylation of a tyrosine kinase (Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase) resulting in unregulated growth of affected lymphoid cells. ALK is activated through chromosomal translocations or inversions with any of several partner genes, most commonly being nucleophosmin (NPM) [12, 13].

In other words, within the spectrum of ALCL the clinical features are determined, among other factors, by the dysregulation of the gene coding for the Nucleophosmin-Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (NPM-ALK) fusion protein. This dysregulation is characterized by ALK positivity of the affected lymphocytes on immunostaining. Primary cutaneous ALCL differs from the systemic form in its clinical features and its almost invariable absence of the ALK protein [13].

ALK positive ALCL mostly occurs in the first three decades of life. This sub-type is quite aggressive in presentation; extranodal involvement is common with the skin being the most common extranodal site affected. ALK positive ALCL generally has a better prognosis and tends to benefit more from chemotherapy, as compared to ALK negative ALCL [14, 15, 16]. Different treatment modalities have been used for ALCL including conventional poly-chemotherapy, radiotherapy and combination of high -dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplant [17, 18]. Recent studies have focused on the possible use of anti-CD30 antibody in ALCL and the future might see the large-scale use of anti-CD30 antibody monotherapy in ALCL [19, 20].

The uniqueness of our case is highlighted by the several features. Firstly, in our case, unlike the usually good prognosis associated with ALK + ALCL, the patient had rapid and progressive deterioration of his condition. We postulate that this might have been partly due to sudden tumor lysis and secondary acute renal failure. Another unique feature in our case was the presentation of an ALK + ALCL in the form of erythroderma. The one major limitation in our case was that we could not do a lymph node biopsy because no clinically significant, enlarged peripheral nodes were available. Moreover the general condition of the patient at the time was unfavorable for a further invasive procedure. However, the very fact that peripheral nodes were not evidently affected along with the multiple, large internal lymph nodes and the ALK positivity, suggested the diagnosis of primary systemic ALCL. Lastly through this study we would also like to raise the possibility of the role of drugs like carbamazepine in inducing true anaplastic lymphomas and possibly an even more aggressive form of an ALK positive ALCL. We cannot rule out DRESS as the cause of the patient's renal failure and rapid demise. The need to maintain a high level of suspicion for early diagnosis and for instituting appropriate treatment in such cases cannot be overstated.

References

1. Choi TS, Doh KS, Kim SH, Jang MS, Suh KS, Kim ST. Clinicopathological and genotypic aspects of anticonvulsant-induced pseudolymphoma syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2003 ;148:730-6. PubMed2. Vittorio CC, Muglia JJ. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:2285-2290. PubMed

3. Tennis P, Stern RS. Risk of serious cutaneous disorders after initiation of use of phenytoin, carbamazepine, or sodium valproate: a record linkage study.Neurology1997; 49:542-546. PubMed

4. Naisbitt DJ, Britschgi M, Wong G, Farrell J, Depta JP, Chadwick DW, Pichler WJ, Pirmohamed M, Park BK. Hypersensitivity reactions to carbamazepine: characterization of the specificity, phenotype, and cytokine profile of drug-specific T cell clones. Mol Pharmacol. 2003; 63:732-41. PubMed

5. Di Lernia V, Viglio A, Cattania M, Paulli M. Carbamazepine-induced, CD30+, primary, cutaneous, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol.2001;137:675-6. PubMed

6. Gül U, Kilic A, Dursun A. Carbamazepine-induced pseudo mycosis fungoides. Ann Pharmacother. 2003 ;37:1441-3. PubMed

7. Albrecht J, Fine LA, Piette W. Drug-associated lymphoma and pseudolymphoma: recognition and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007 ;25:233-44. PubMed

8. Ploysangam T, Breneman DL, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 ; 38: 877-95. PubMed

9. Katzin WE, Julius CJ, Tubbs RR, McHenry MC. Lymphoproliferative disorders associated with carbamazepine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990 Dec;114(12):1244-8. PubMed

10. Singh G, Driever PH, Sander JW. Cancer risk in people with epilepsy: the role of antiepileptic drugs. Brain. 2005;128:7-17. PubMed

11. Stein H, Foss HD, Dürkop H, Marafioti T, Delsol G, Pulford K, Pileri S, Falini B. CD30 (+) anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a review of its histopathologic, genetic, and clinical features. Blood. 2000; 96:3681-95. PubMed

12. Kadin ME, Carpenter C. Systemic and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol 2003;40:244-56. PubMed

13. Su LD, Schnitzer B, Ross CW, Vasef M, Mori S, Shiota M, Mason DY, Pulford K, Headington JT, Singleton TP. The t(2,5)-associated p80 NPM-ALK fusion protein in nodal and cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:597. PubMed

14. Falini B, Pileri S, Zinzani PL, Carbone A, Zagonel V, Wolf-Peeters C, Verhoef G, Menestrina F, Todeschini G, Paulli M, Lazzarino M, Giardini R, Aiello A, Foss HD, Araujo I, Fizzotti M, Pelicci PG, Flenghi L, Martelli MF, Santucci A. ALK+ lymphoma: clinico-pathological findings and outcome. Blood. 1999;93:2697. PubMed

15. Gascoyne RD, Aoun P, Wu D, Chhanabhai M, Skinnider BF, Greiner TC, Morris SW, Connors JM, Vose JM, Viswanatha DS, Coldman A, Weisenburger DD. Prognostic significance of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) protein expression in adults with anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;93:3913. PubMed

16. Shiota M, Nakamura S, Ichinohasama R, Abe M, Akagi T, Takeshita M, Mori N, Fujimoto J, Miyauchi J, Mikata A, Nanba K, Takami T, Yamabe H, Takano Y, Izumo T, Nagatani T, Mohri N, Nasu K, Satoh H, Katano H, Fujimoto J, Yamamoto T, Mori S. Anaplastic large cell lymphomas expressing the chimeric protein p80 NPM/ALK: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Blood. 1995;86:1954. PubMed

17. Fanin R, Silvestri F, Geromin A, Cerno M, Infanti L, Zaja F, Barillari G, Savignano C, Rinaldi C, Damiani D A, Baccarani M. Primary systemic CD30 (Ki-1)-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the adult: sequential intensive treatment with F-MACHOP regimen (+ radiotherapy) and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;87:1243. PubMed

18. Shehan JM, Kalaaji AN, Markovic SN, Ahmed I. Management of multifocal primary cutaneous CD 30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:103-110. PubMed

19. Duvic M, Kunishige J, Kim Y, Reddy S, Forero A, Pinter-Brown L, et al. Phase II preliminary results suggest SGN30 (anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody) is active and well-tolerated in patients with cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol 2006:126(S4) Abs 268.

20. Wahl AF, Klussman K, Thompson JD, Chen JH, Francisco LV, Risdon G, Chace DF, Siegall CB, Francisco JA. The anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody SGN-30 promotes growth arrest and DNA fragmentation in vitro and affects antitumor activity in models of Hodgkin's disease. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3736-42. PubMed

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal