Extramammary Paget disease: Immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D31g0833bkMain Content

Extramammary Paget disease: Immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers

Etienne CE Wang BA (Hons) MBBS (Hons), Yung Chien Kwah MBBS MRCP (UK) MRCPS (Glas) FAMS, Wee Ping Tan MBBS MRCP (UK), Joyce

SS Lee MMED (UK) FAMS, Suat Hoon Tan MBBS MMed DipRCPath

Dermatology Online Journal 18 (9): 4

National Skin Centre, SingaporeAbstract

Extra-mammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intra-epithelial carcinoma that is usually found on the apocrine-rich skin of the perineum. We report 2 cases in which EMPD was initially misdiagnosed on the initial punch biopsy as melanoma-in-situ and Bowen disease respectively. Reasons for the misdiagnoses included a rare pigmented axillary variant of EMPD in the first case and atypical bowenoid features on H&E in the second. The cases are described with a critical review of the histopathological findings, along with a review of the current literature. This highlights the necessity of a comprehensive immunohistochemical panel for the assessment of intra-epithelial pagetoid atypical cells.

Introduction

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intra-epithelial adenocarcinoma that presents classically as an erythematous plaque on the genital skin of elderly patients. Its clinical differential diagnoses may include cutaneous candidiasis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, or Bowen disease. The histological features of EMPD are more striking – with mucin-rich Paget cells in the epidermis. However, rare variants of EMPD, such as the pigmented and bowenoid variants, exist as potential confounders. Awareness of these variants is important in the accurate diagnosis and management of elderly patients presenting with such lesions.

Herein we describe two cases of EMPD, which were initially misdiagnosed as melanoma-in-situ and Bowen disease, respectively, with an analysis of the histopathological findings and clinico-pathological correlation.

Case report 1

A 76-year-old man presented for treatment of asteatotic eczema and prurigo nodules on his forearms. He had no other significant medical history. On physical examination, he was incidentally found to have an asymptomatic variegated brownish plaque in his left axilla (Figure 1). This was diagnosed clinically as a flat seborrheic keratosis.

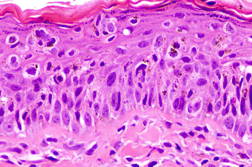

Punch biopsy of this lesion revealed atypical cells with nuclear pleomorphism and melanin-laden cytoplasm within the epidermis. These cells were arranged in nests and singly along the basal layer, and showed pagetoid spread at various levels of the epidermis. A histopathological diagnosis of melanoma-in-situ was made (Figure 2). The lesion was excised with a 10 mm margin.

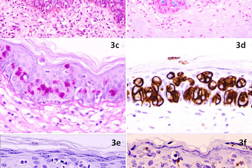

The excision specimen was sent for histopathological examination (Figures 3a through 3e). As seen in the earlier punch biopsy specimen, there were nests of atypical cells with melanin pigmentation within their cytoplasm showing pagetoid involvement of the epidermis. Also identified were cells with abundant basophilic cytoplasm, with signet ring cell forms. These cells stained positively with Alcian Blue and PAS-diastase stains, confirming the presence of mucin. On immunohistochemistry, the pagetoid cells stained strongly positively for cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). These cells stained negatively for cytokeratin 20 (CK20), high molecular weight cytokeratin 34βE12, and the melanocytic markers S-100, Melan-A and HMB45. Dendritic processes from melanocytes ramified throughout the entire epidermis in close association with the Paget cells as seen on Melan-A stain (Figure 3f). The first punch biopsy specimen was subsequently reviewed and the atypical Paget cells containing melanin were also found to stain positively for CK7, negatively for S-100, and weakly positively for Alcian blue and PAS-diastase. Thus, the final diagnosis of pigmented Extramammary Paget Disease (EMPD) of the axilla was made.

The patient was referred for a malignancy screen of the urogenital and colorectal tracts. Urological assessment included a prostate specific antigen (PSA) level, which was elevated at 24.7 ng/ml; a subsequent transrectal biopsy revealed a Gleason 3 + 4 prostate adenocarcinoma. Retrospective immunostaining of the excision specimen from the axilla showed that the atypical Paget cells were negative for PSA (Figure 3e). He was scheduled for hormonal therapy, followed by radiotherapy. A colonoscopy and nasendoscopy were negative for malignancy.

Case report 2

A 77-year-old man presented with an indurated plaque over his left scrotum of 2 years duration. This lesion had been diagnosed previously as Bowen disease after a biopsy two years ago. Despite treatment with carbon dioxide laser ablation and cryotherapy, the plaque persisted and increased in size (Figure 4).

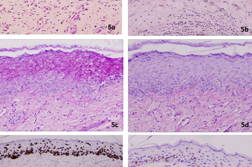

Punch biopsies of two sites of the lesion was performed and showed on histopathological examination to have a thickened epidermis that was replaced with atypical cells with loss of polarity. The atypical cells extended into the upper epidermis, along the follicular epithelium, and were accompanied by mitotic figures. PAS stain was positive and diastase digestible, indicating the presence of glycogen; mucicarmine and Alcian blue stains did not demonstrate the presence of mucin (Figures 5a through 5d). No immunohistochemical stains were done at this stage. This was diagnosed as persistent squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ, and complete surgical excision was performed.

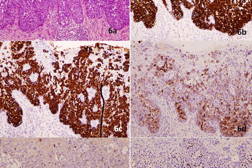

The excised specimen was submitted for histopathological examination and revealed EMPD (Figures 6a through 6f). Tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were seen singly and in clusters within the thickened epidermis, as well as extending down the hair follicles and sweat ducts. The tumor cells displayed brisk mitoses, pleomorphic vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli with focal lumen differentiation. These cells were positive for mucin. The lobules of atypical cells seen in the dermis amidst the benign sweat glands were most likely the adnexal component of the EMPD.

Retrospective immunostaining of the initial biopsy specimen showed a profile in keeping with EMPD: CAM 5.2+, CK7+, EMA+, CEA+, and negative staining for CK20, p63, and S100.

Investigations including chest radiography, CT colonoscopy, flexible cystoscopy, ultrasound of his scrotum, and other tumor markers did not reveal any internal malignancy. He continues to be under follow up.

Discussion

Cutaneous Paget disease refers to a spectrum of intra-epithelial adenocarcinoma. It was first described in 1874 as Mammary Paget Disease (MPD), affecting the nipple or areolar skin of the breast, commonly associated with an underlying carcinoma of the mammary lactipherous ducts [1]. Fifteen years later in 1889, the extra-mammary variant was described [2]. Extramammary Paget Disease (EMPD) has many clinical and histopathological similarities to MPD, but differs in its pathogenesis and epidemiology.

EMPD typically presents in the apocrine-rich skin of the perineum, groin, and, less commonly, the axillae. It usually appears as a well-demarcated red or brown plaque, with variable areas of induration, crusting, scaling, or ulceration. Initial differential diagnoses may include seborrheic dermatitis, Bowen disease, flexural psoriasis, eczema, or tinea infection. The diagnosis of EMPD is usually suspected because of the persistence and lack of clinical response to topical anti-inflammatory or anti-fungal medications.

Whereas MPD always indicates an underlying ductal carcinoma of the breast, the association with underlying malignancies in EMPD is less certain. EMPD may be primary or secondary. Primary EMPD comprises the majority of cases and is believed to arise from cutaneous adnexal glandular epithelium; it is not associated with underlying malignancies. The Paget cells in secondary EMPD are thought to be epidermotropic metastatic cancer cells from the visceral adenocarcinoma.

EMPD occurs most commonly on the vulva, which comprises 65 percent of all cases of EMPD [3]. Amongst vulval EMPD, 4-17 percent are associated with an underlying adnexal carcinoma and 10-20 percent are associated with a distant adenocarcinoma of the breast, genitourinary, or gastrointestinal tracts [4]. EMPD of the male groin and scrotum accounts for 14 percent of EMPD cases and may be associated with an underlying carcinoma of the prostate, bladder, ureter, or kidneys in 11 percent of cases [5]. Perianal EMPD affects both sexes equally and comprises about 20 percent of EMPD cases. It is associated with distant adenocarcinoma of the rectum, breast, stomach, or uterus in 15-45 percent of cases [6].

Our first patient presented with a pigmented EMPD in the axilla. Axillary EMPD is very rare, with the majority noted to be in Japanese patients in a recent review [7]. Our patient is of Chinese descent. Isolated axillary EMPD was more common in women, with an association with underlying breast cancer. “Triple EMPD” patients, with involvement of the axillary and genital skin, were more likely to be male (94.3%) and have so far only been described in the Japanese population. This same review describes a patient presenting with a pigmented EMPD in the axillae, which was also initially misdiagnosed as a melanoma-in-situ.

Both MPD and EMPD have pigmented variants, which may resemble melanoma-in-situ clinically and histologically [8]. Pigmented MPD has even been reported to exhibit similar features to melanoma on dermoscopy [9]. To date, about 17 cases of pigmented MPD have been reported [10] and there are even fewer cases of pigmented EMPD [11, 12, 13]. Three of these cases were reported in female patients with EMPD of the vulval or perineal region; on histopathological examination they had intraepidermal Paget cells with abundant cytoplasm and distinct melanin pigment. A case series by Petersson et al [8] described 3 cases of pigmented EMPD and 4 pigmented MPDs. The authors found that the Paget cells were in close approximation to dendritic melanocytes and transfer of melanin from melanocytes to the Paget cells was the likely mechanism of pigmentation of the lesions. On punch biopsy specimens, the restricted snapshot of the lesion’s architecture in addition to the increased melanin pigment within and around the Paget cells may lead to a misdiagnosis of melanoma-in-situ.

The limitations of a punch biopsy in diagnosing EMPD are further illustrated in our second patient in whom an initial diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ was made. Perineal EMPD may be clinically indistinguishable from Bowen disease and both conditions have even been reported to co-exist [14]. It might also be difficult to distinguish EMPD and Bowen disease based on histological analysis alone because intra-epidermal clear cells may be seen in both disorders [15, 16, 17, 18] On H&E, the identification of spinous processes around the atypical cells may be helpful in distinguishing the atypical keratinocytes of Bowen disease from the atypical Paget cells of EMPD. Paget cells contain neutral mucopolysaccharides, which stain positively with PAS-diastase, mucicarmine, and Alcian blue, whereas the atypical keratinocytes of Bowen disease do not. However, staining for mucin alone does not provide sufficient criteria for excluding EMPD because the stains may give false-negative results associated with the sampling problems of small biopsies.

Pagetoid Bowen disease also occurs in about 5 percent of squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ and may demonstrate nests of cells with pale staining cytoplasm in the epidermis [19. Rarely, these cells may even express cytokeratin (CK) 7 [20]. There have also been case reports of EMPD with features of Bowen disease, whereby portions of the lesion exhibited acanthosis and full-thickness cellular atypia without characteristic Paget cells, but stained positive for CEA, CK7, and CAM5.2 [21].

Thus, it is recommended that when encountering a tumor with intra-epidermal atypia in a site known to be rich in apocrine glands (i.e., the groin, perineum, axillae), a screening panel of immunohistochemical markers that include melanocytic markers such as S100, Melan-A, HMB-45, high molecular weight cytokeratins, CEA, and CK7 should be carried out to fully characterize the lesion [22, 23]. A recent paper suggests that p63 might be a useful marker to differentiate Bowen disease from EMPD; p63 stains atypical keratinocytes of Bowen's disease positively but does not stain EMPD cells [24]. Indeed, a retrospective immunostain of a biopsy specimen in Patient 2 confirmed the diagnosis of EMPD with a profile of CAM5.2+, EMA+, CK7+, CK20–, p63–, and S100–.

This distinction is important because EMPD may be associated with a visceral malignancy and diagnosis should prompt a comprehensive age-appropriate cancer screen. A large review of 197 cases of EMPD showed that up to 29 percent of cases were associated with an internal malignancy [5]. This early review also showed that all 4 of the male genitourinary malignancies presented with EMPD of the male genitalia and 8 out of 9 gastrointestinal tract malignancies were associated with perianal EMPD. Indeed, a more recent comprehensive review by Lam et al showed an over-representation of GU and GI tract malignancies in EMPD [25]. There have also been reports of EMPD associated with breast cancer, lending support to the possibility that EMPD may represent an epidermotropic metastasis in some cases. Bowen disease, on the other hand, is not known to be associated with distant cancers, unless it occurs in the setting of arsenical exposure. The identification of an axillary EMPD should also prompt a thorough skin examination for concomitant involvement of the contralateral axillary and genital skin.

The main characteristics of these three malignancies are summarized in Table 1. As clinical and histopathological features commonly overlap, immunostains (in bold) are essential for clinching the diagnosis.

The gold standard of treatment of EMPD is Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) because this provides margin control in a tumor known to have diffuse spread beyond the clinically apparent margins. Recurrence rates for MMS were 16 percent for primary EMPD and 50 percent for recurrent EMPD, compared to 33-60 percent for non-MMS procedures [26]. If MMS cannot be offered, wide local excision with margins of 1 to 5 centimeters have been quoted to have excellent results [27].

For patients unsuitable for surgery, or who decline surgery, other modalities that have been described with success in the treatment of EMPD include electrodessication and curettage, radiotherapy [28], photodynamic therapy [29, 30], and topical Imiquimod [31].

References

1. Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. St Bartholomew Hosp Res Lond 1874; 10: 87–9.2. Crocker H. Paget’s disease affecting the scrotum and penis. Trans Pathol Soc London 1889; 40: 187–91.

3. Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies-Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG 2005; 112: 273-9. [PubMed]

4. Fanning J, Lambert H, Hale TM, Morris PC, Schuerch C. Paget’s disease of the vulva: prevalence of associated vulvar adenocarcinoma, invasive Paget’s disease, and recurrence after surgical excision. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 180: 24–7. [PubMed]

5. Chanda J. Extramammary Paget’s disease: prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985; 13: 1009–14. [PubMed]

6. McCarter M, Quan S, Busam K et al. Long-term outcome of perianal Paget’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 612–6. [PubMed]

7. Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol 2009; 36(9): 995-1000. [PubMed]

8. Petersson F, Ivan D, Kazakov DV, Michal M, Prieto VG. Pigmented Paget disease--a diagnostic pitfall mimicking melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009; 31: 223-6. [PubMed]

9. Hida T, Yoneta A, Nishizaka T et al. Pigmented mammary Paget’s disease mimicking melanoma: report of three cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2012; 22: 121-4. [PubMed]

10. Soler T, Lerin A, Serrano T. Pigmented Paget’s Disease of the Breast Nipple with underlying Infiltrating carcinoma: A Case Report and Review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011; 33: e54-7. [PubMed]

11. Vincent J, Taube JM. Pigmented extramammary Paget disease of the abdomen: a potential mimicker of melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2011; 17: 13. [PubMed]

12. Gumurdula D, Sung CJ, Lawrence WD. Pathologic quiz case: a 63-year-old woman with a pigmented perineal lesion. Extramammary Paget disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004; 128: e23-4. [PubMed]

13. Chiba H, Kazama T, Takenouchi T, et al. Two cases of vulval pigmented extramammary Paget's disease: histochemical and immunohistochemical studies. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 142(6): 1190 [PubMed]

14. Kim S, Kwon JI, Jung HR, Lee KS, Cho JW. Primary Extramammary Paget’s Disease combined with Bowen’s disease in vulva. Ann Dermatol. 2011; 23: S222-5. [PubMed]

15. Jones RE Jr , Austin C , Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical re-examination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979; 1: 101–32. [PubMed]

16. Cannavo SP, Guarneri F, Napoli P. Extramammary Paget's disease of the scrotum with Bowenoid features. Eur J Dermatol. 2006; 16(2): 203. [PubMed]

17. Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, Zhang G, Shi H, Cao S. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010; 37(6): 683. [PubMed]

18. Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic Anaplastic Extramammary Paget’s Disease: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Annals of dermatology. 2011; 23: S226-30. [PubMed]

19. Raju RR, Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the external genitalia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003; 22: 127-35. [PubMed]

20. Williamson JD, Colome MI, Sahin A, Ayala AG, Medeiros LJ . Pagetoid Bowen disease: a report of 2 cases that express cytokeratin 7. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000. 124:427–30. [PubMed]

21. Quinn AM, Sienko A, Basrawala Z, Campbell SC. Extramammary Paget Disease of the scrotum with features of Bowen’s Disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004; 128: 84-6. [PubMed]

22. Shah KD, Tabibzadeh SS, Gerber MA. Immunohistochemical distinction of Paget’s disease from Bowen’s disease and superficial spreading melanoma with the use of monoclonal cytokeratin antibodies. Am J Clin Path. 1987; 88: 689-95. [PubMed]

23. Nagai Y, Ishibuchi H, Takahashi M, et al. Extrammamary Paget’s disease with bowenoid histologic features accompanied by an ectopic lesion on the upper abdomen. J Dermatol. 2005; 32: 670-3. [PubMed]

24. Memezawa A, Okuyama R, Tagami H, Aiba S. p63 constitutes a useful histochemical marker for differentiation of pagetoid Bowen’s disease from extramammary Paget's disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008; 88: 619-20. [PubMed]

25. Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s Disease: Summary of Current Knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010; 28: 807-26. [PubMed]

26. Hendi A, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Extramammary Paget’s disease: surgical treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004; 51: 767-73. [PubMed]

27. Murata Y, Kumano K. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the genitalia with clinically clear margins can be adequately resected with 1cm margin. Eur J Dermatol. 2005; 15: 168-70. [PubMed]

28. Son SH, Lee JS, Kim YS et al. The role of radiation therapy for the extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva: experience of 3 cases. Cancer Res Treat. 2005; 37(6): 365-9. [PubMed]

29. Housel JP, Izikson L, Zeitouni NC. Non-invasive extramammary Paget’s disease treated with photodynamic therapy: case series from the Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Dermatol Surg. 2010; 36(11): 1718-24. [PubMed]

30. Shieh S, Dee AS, Cheney RT et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 146(6): 1000-5. [PubMed]

31. Berman B, Spencer J, Villa A et al. Successful treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease of the scrotum with imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003; 28 (Suppl 1): 36-8. [PubMed]

32. Lentini M, Le Donne M. Asymmetrically Pigmented Patch on the vulvo-perineal area: A Quiz. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011; 91(3): 380-3. [PubMed]

33. Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010; 62(4): 597-604. [PubMed]

© 2012 Dermatology Online Journal