Plasma cell predominant B cell pseudolymphoma

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D392k8524sMain Content

Plasma cell predominant B cell pseudolymphoma

Stephen J Nervi MD, RA Schwartz MD MPH

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (10): 12

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityAbstract

A 46-year-old woman with no history of foreign travel presented to the New Jersey Medical School Dermatology Clinic in July, 2007, with pruritic ulcerating facial masses that had been present since October, 2006. Clinical and histopathologic findings were most consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous plasma cell predominant B cell pseudolymphoma. An extensive search using special stains for an etiologic organism was negative. The term cutaneous pseudolymphoma has been coined to describe the accumulation of either T or B cell lymphocytes in the skin that is caused by a nonmalignant stimulus and encompasses several different terms depending on etiology. In cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma where a cause is identified, treatment entails removing the underlying causative agent. Idiopathic cases tend to be recalcitrant to treatment.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

History

A 46-year-old woman presented to the New Jersey Medical School Dermatology Clinic in March, 2007, with pruritic, ulcerating, facial masses that had been present since October, 2006. Prior to being seen in our clinic, she was given several possible diagnoses by community dermatologists that included keloids, cutaneous abscesses, pyoderma, and WellÕs syndrome. Several unsuccessful therapeutic measures had been tried for these possible diagnoses that included incision and drainage, topical and oral antibiotics, and topical glucocorticoids. The patient has a history of diabetes mellitus type II for which she takes pioglitizone- metformin HCl; she began taking this medication after developing her skin lesions. She was born and raised in Jersey City, NJ and has no history of foreign travel.

Physical Examination

On the nasal bridge there was a 4-x 3-cm, crusted, pink/hyperpigmented plaque with central ulceration and a few surrounding hyperpigmented macules. On the right helix there was a 3-x 2-cm, violaceous plaque with scale-crust. A 3-mm, hyperpigmented papule was present on the right cheek. Overlying the right mandibular angle and left cheek there was 3-x-2cm, crusted, violaceous plaques. The left lateral upper eyelid had a 1- cm, violaceous nodule at the lid margin. Similar violaceous plaques also were present on the areola and left shin. The plaques were non-tender to palpation and have no purulent or bloody drainage.

Lab

A complete blood count showed eosinophilia of 13 percent and thrombocytosis of 520 T/uL. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 18 mm/hr. Bacterial cultures grew Serratia marcescens and Staphylococcus aureus on separate occasions. A completed tomography scan of the head showed multiple, soft tissue densities and prominent lymph nodes. Complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibodies, complement levels, human immunodeficiency virus test, rapid plasma reagin test, and mycobacterial and fungal cultures were either non-reactive or normal.

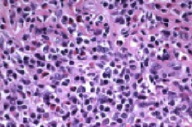

Histopathology

There is a diffuse, dermal inflammatory infiltrate, which is composed of plasma cells and eosinophils with sparse infiltration of subcutaneous fat. A Giemsa stain shows no evidence of leishmaniasis or other intracellular parasites. Special stains (Warthin Starry, Gram, periodic acid-Schiff, Gomori methenamine silver, acid-fast bacillus,) are negative for spirochetes, bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli. A CD 30 immunostain identifies rare activated lymphocytes. T-cell markers (CD 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8) and B cell markers (CD 79a and CD 20) show a sparse population of lymphocytes consistent with an admixed inflammatory infiltrate. Flow cytometry analysis and kappa and lambda light chain immunostains show a polyclonal plasma cell population.

Comment

The term cutaneous pseudolymphoma has been coined to describe the accumulation of either T or B cell lymphocytes in the skin that is caused by a nonmalignant stimulus. Cutaneous B cell pseudolymphoma (CBPL) encompasses several different terms depending on etiology and includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphocytoma cutis, sarcomatosis cutis of Spiegler-Fendt, and Bafverstedt syndrome [1]. It is helpful to conceptualize CBPL as the benign counterpart of a spectrum of lymphoproliferative disease that includes cutaneous lymphoma [1]. Most cases are considered idiopathic; however, several associations have been identified [2, 3, 4]. These include medications, vaccinations or other injections including tattoos, contact allergens, arthropod bites, post-zoster scars, and infections that include Borrelia burgdorferi and Leishmania donovani [5-11].

Cutaneous B cell pseudolymphoma usually arises on the face, chest, or upper extremities as asymptomatic, solitary, skin-colored-to-violaceous plaques, nodules, or tumors. It is more frequent in whites and women, and the majority of patients are under 40 years of age [1]. Differentiation from cutaneous B-cell lymphoma with histopathology alone is difficult and requires a sufficiently deep incisional biopsy; excisional biopsy may be required for complete analysis [11]. Features indicating CBPL include a nodular or diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate and various numbers of plasma cells, histiocytes, and eosinophils predominantly in the papillary dermis. Plasma cells rarely may be the most numerous cell type present as in this case [12]. Flow cytometry analysis indicating a polyclonal lymphocytic population helps differentiate this condition from a monoclonal cutaneous B-cell lymphoma.

In cases of cutaneous pseudolymphoma where a cause is identified, treatment entails removing the underlying causative agent. Idiopathic cases tend to be recalcitrant to treatment. Some lesions may resolve while others may persist and even grow over months to years. Various reported treatments include topical or intralesional glucocorticoids, surgical excision, cytotoxic agents, interferon, antimalarials, and other topical or intralesional therapies [1, 2, 3, 4, 14].

References

1. Ploysangam T, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38: 877 PubMed2. Lackey JN, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: a case report and brief review of the literature. Cutis 2007; 79: 445 PubMed

3. Setyadi H, et al. The solitary lymphomatous papule, nodule, or tumor. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007: [Epub ahead of print] PubMed

4. Bergman R, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia presenting as a solitary facial nodule. Arch Dermatol 2006; 142: 1561 PubMed

5. Ban M, et al. Cutaneous plasmacytic pseudolymphoma with erythroderma. Int J Dermatol 1998 37; 10: 778 PubMed

6. Albrecht J, et al. Drug-associated lymphoma and pseudolymphoma: recognition and management. Dermatol Clin 2007; 25: 233 PubMed

7. Flaig MJ, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma in association with Leishmania donovani. Br J Dermatol 2007; 157: 1042 PubMed

8. Paley K, et al. Cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma due to paraphenylenediamine.Am J Dermatopathol 2006; 28: 438 PubMed

9. Moreira E, et al. Postzoster cutaneous pseudolymphoma in a patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 1112 PubMed

10. Maubec E, et al. Vaccination-induced cutaneous pseudolymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52: 623 PubMed

11. Colli C, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi-associated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2004; 31: 232 PubMed

12. Lee MW, et al. Clinicopathologic study of cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Dermatol 2005; 32: 594 PubMed

13. Bouloc A, et al. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of immunoglobin gene rearrangement in cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135: 168 PubMed

14. Dionyssopoulos A, et al. T- and B-cutaneous pseudolymphomas treated by surgical excision and immediate reconstruction. Derm Surg 2006; 32: 1526 PubMed

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal