Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D38pv0v7c5Main Content

Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy

Bahar F Firoz MD MPH, Christopher M Hunzeker MD, Anthony C Soldano MD, Andrew G Franks Jr MD

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (5): 11

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityAbstract

A 75-year-old woman with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis presented with a 2-month history of progressive skin thickening of the lower extremities. A punch biopsy specimen showed plump fibroblasts entrapping collagen bundles and positive staining for CD34 and procollagen. These changes were consistent with a diagnosis of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy is a rare, sclerosing disorder in patients with renal failure, which may be mistaken for scleromyxedema. The etiology of NFD is unclear but may be associated with systemic involvement, antecedent surgical procedures, gadolinium, or an underlying hypercoagulable state. The treatment is limited: a few reported cases have shown remission after stopping dialysis in transient renal failure.

Clinical synopsis

A 75-year-old woman presented to the Charles Harris Skin and Cancer Pavilion in August 2006 with a 2-month history of progressive skin tightening and hardening of both legs. The skin started to swell and feel hard on both upper thighs, which progressed to involve both lower legs. She denied pain, antecedent erythema, or edema of her legs. She complained of progressive difficulty with walking and moving her lower extremities. She denied difficulty swallowing, photosensitivity, or Raynaud phenomenon. The patient had received no treatment. No other skin or mucosal areas were involved. Medical history includes diabetes-mellitus-induced, end-stage renal disease, which was treated with hemodialysis for 7 years. Approximately 10 years prior, breast cancer was treated successfully with lumpectomy and radiation therapy; she is currently in remission. In June 2006 a non-small-cell lung cancer was diagnosed and treated with radiation therapy; her last treatment was in August 2006. During a lung cancer evaluation, the patient had a brain magnetic resonance imaging study with and without gadolinium contrast in June 2006, one month prior to the onset of the skin symptoms. She also had a thyroidectomy for goiter and takes thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Physical examination

Bound-down, hard, indurated plaques extended from the ankles to the medial aspects of both thighs. Mild pitting edema of the lower extremities was present with absence of hair. No involvement of the arms, trunk, head, or neck was noted. There was no erythema or hyperpigmentation.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

Laboratory data

The urea nitrogen was 51 mg/dL (range 7-30), creatinine 5.5 mg/dL (range 0.5-1.2), free T4 2.8 ng/dL (range 0.8-2.7), and low white-cell count 3.5 x 103/mcL (range 3.8-10.8). A lipid profile and liver function tests were normal. Anti-scl-70, anti-smith, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti-Ro, and anti-La antibodies, serum protein electrophoresis, and urine protein electrophoresis were negative.

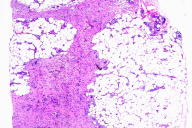

Histopathology

Within the subcutis is an infiltrate of slightly plump spindle cells which expands the subcutaneous septa and encroaches on adipocytes, entraps collagen bundles, and shows a vague streaming pattern. These cells stain positively for procollagen I and are focally positive for CD34. Intermixed are smaller numbers of stellate epithelioid cells, many of which contain hemosiderin, which is highlighted with Perls' potassium ferrocyanide stain. Abundant mucin is found interposed between the spindle cells by hematoxylin-eosin and colloidal-iron stains. Evidence of chronic vascular stasis is not apparent.

Comment

Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD) is a rare condition in patients with renal insufficiency, which is characterized by diffuse hardening and thickening of the skin most commonly on the extremities. First described in 2000 [1], the etiology of this disease is still unknown; however, all patients have acute, chronic, or transient renal failure. The severity of NFD is not related to the underlying cause of renal failure or the degree of renal impairment [2]. In cases of reversible renal failure, the improvement of kidney disease usually heralds an improvement in NFD. The clinical presentation of NFD resembles scleroderma or scleromyxedema although there are a few key differences. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy characteristically presents symmetrically on the extremities and trunk. A common distribution is between the ankles and mid-thighs and between the wrists and mid-upper arms. Occasionally swelling of the hands and feet is evident. The lesions of NFD do not typically involve the face, unlike scleredema, scleromyxedema, or systemic sclerosis [3]. The primary lesions are skin-colored-to-erythematous papules that coalesce into plaques that may have an erythematous-to-brawny or peau d'orange appearance. The involved skin becomes thick and woody in texture, and joint contractures may rapidly develop. Whereas scleromyxedema may be associated with IgG paraproteinemia, nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy is not. Systemic involvement in NFD may occur, which is labeled nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and involves the heart, lungs, muscles, tendons, or peripheral nerves [4]. The etiology and pathophysiology of NFD is unknown. The recent emergence and clustering of cases at major medical and renal transplant centers suggests a toxic or infectious agent, although no studies confirm this [2]. A recent article raises the question of whether gadolinium-enhanced imaging studies, which are typically performed 2-4 weeks prior to disease onset, may trigger the development of NFD in susceptible persons [5]. In patients with normal renal function, the half-life of gadolinium is approximately 2 hours. In patients with renal failure, it can range between 30 to 120 hours, which can possibly lead to deposition in muscle, bone, and other tissues. This patient had a gadolinium contrast study 1 month prior to the onset of symptoms, which may be the triggering factor. Another study found that myofibroblasts were involved, which are cells with characteristics of both fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells [6]. In normal wound repair myofibroblasts disappear, but they persist in NFD and lead to chronic fibrosis. Hypercoagulability or thrombotic episodes have been reported in up to 12 percent of patients with NFD. One case series identified positive anti-cardiolipin antibodies in four patients [7]. Deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, factor V Leiden, antiphospholipid antibodies, antithrombin III deficiency, and protein C and S deficiencies, have all been reported with NFD [2, 8]. Approximately 15 percent of patients have had an associated antecedent surgical procedure, most often a vascular reconstructive procedure. An appreciable number have chronic liver disease and some have idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [2]. There is no consistently effective therapy for NFD. In the literature, 28 percent of patients died, 28 percent had no improvement, and only 20 percent had modest improvement [4]. Case reports have described the use of different therapeutic modalities, which include cyclosporine [7], tacrolimus ointment [7], oral and topical glucocorticoids [9], calcipotriene ointment, photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid [10], thalidomide, ultraviolet light A1 phototherapy [11], interferon-alpha [9], cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis [12], intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) [13], and photopheresis [14]. Only cases treated with ultraviolet A1 phototherapy, plasmapheresis, interferon-alpha, and IVIg showed mild improvement.

References

1. Cowper SE, et al. Scleromyxedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet 2000;356:10002. Cowper SE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: the first six years. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2003;15:785

3. Rebora A, et al. Mucinoses. In Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. New York:Mosby, 2003:647

4. Mendoza FA, et al. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2006:35;238

5. Grobner T. Gadolinium - a specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006: 21:1104

6. Swartz RD, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: a novel cutaneous fibrosing disorder in patients with renal failure. Am J Med 2003:114;563

7. Mackay-Wiggan JM, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (scleromyxedema-like illness of renal disease). J Am Acad Dermatol 2003:48;55

8. Cowper SE, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Am J Dermatopathol 2001:23;383

9. Hubbard V, et al. Scleromyxedema-like changes in four renal dialysis patients. Br J Dermatol 2003:148;563

10. Schmook T, et al. Successful treatment of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy in a kidney transplant recipient with photodynamic therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005:20;220

11. Kafi R, et al. UV-A1 phototherapy improves nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Arch Dermatol 2004:140;1322

12. Baron PW, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy after liver transplantation successfully treated with plasmapheresis. Am J Dermatopathol 2003;25:204

13. Chung HJ, et al. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: response to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Brit J Dermatol 2004:150;596

14. Gilliet M, et al. Successful treatment of three cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy with extracorporeal photopheresis. Br J Dermatol 2005: 152;531

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal