Clinical spectrum of cutaneous leishmaniasis: An overview from Pakistan

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D38k3992krMain Content

Clinical spectrum of cutaneous leishmaniasis: An overview from Pakistan

Arfan ul Bari MBBS MCPS FCPS

Dermatology Online Journal 18 (2): 4

Department of Dermatology, CMH, Peshawar, PakistanAbstract

The clinical spectrum of leishmaniasis encompasses subclinical (inapparent), localized (skin lesions), and disseminated infection (cutaneous, mucosal, or visceral). The clinico-pathological picture of cutaneous leishmaniasis is variable and depends not only on the leishmania species but also on endemic region, host factors, and immuno-inflammatory responses. Symptomatic disease is subacute or chronic and diverse in presentation and outcome. Pakistan is one of the countries in which cutaneous leishmaniasis is becoming an epidemic disease and because of its morbidity and disfiguring scars, it is considered a serious public health problem. This is an attempt to review the clinical spectrum of old world cutaneous leishmaniasis, classical and unusual clinical presentations, occurring in Pakistan.

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a protozoan disease with diverse clinical manifestations, which are dependent both on the species of the organism and on the immune response of the host. The disease is spread by the bite of many different species of phlebotomine sandflies, which inject the parasites into their hosts [1, 2]. Over the past few years leishmaniasis in Pakistan has increased at a considerable rate and has also extended its geographic distribution [3, 4]. On the one hand, it is found in the northern hilly areas and on the other in Lasbella and Makran coastal areas in the extreme southern part of the country, along with scattered foci in Punjab, NWFP, and Azad Kashmir [3, 4, 5]. The disease is endemic in Balochistan, with the maximum incidence reported from Sibbi, Chaman, Loralai, Kohlu, Duki, Khuzdar, Dera Bugti, Ziarat, Lehri, Nushki, Uthal, Turbat, Mand and the suburbs of Quetta [6, 7].

Clinical picture

In Pakistan, CL is either caused by Leishmania major (zoonotic) or Leishmania tropica (anthroponotic). Classically it affects the exposed parts of the body and presents with a skin ulcer at the site of a sandfly bite. It generally heals spontaneously within a year but the clinico-pathological picture of cutaneous leishmaniasis is variable depending upon several host parasite related factors. The incubation period is usually measured in months, but may range from a few days to over a year. The initial lesion appears as a red furuncle-like papule. The papule gradually enlarges in size over a period of several weeks and assumes a more dusky violaceous hue. Eventually the lesion becomes crusted with an underlying shallow ulcer, often having raised and somewhat indurated borders. The healing is usually with a scar that is typically atrophic, hyperpigmented, and irregular (cribriform). In addition, the classical types may often show a clustering of lesions, skin crease orientation, volcanic nodules, satellite papules, subcutaneous nodules, and iceberg nodules [1, 2, 6, 7]. Some other uncommon morphological features of localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, in addition to the above-mentioned classical picture, are described in following sections.

Classifications of cutaneous leishmaniasis

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 1a |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Acute, wet, rural or zoonotic type of cutaneous leishmaniasis Figure 1a. Initial furunculoid lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis | |

|  |

| Figure 1b | Figure 1c |

|---|---|

| Figure 1b. An infiltrated plaque with central crust and underlying ulcer Figure 1c. A large erythematous scaly and crusted plaque with central ulceration | |

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is categorized on various grounds such as geography, epidemiology, etiology, course, and clinical pattern of disease, but generally it is classified as zoonotic (wet/rural/early ulcerative type caused by L. major) (Figure 1) or anthroponotic infection (dry/urban/late ulcerative related to L. tropica) (Figure 2). Zoonotic CL is acquired in rural areas from rodents. After a short incubation period, which is less than 8 weeks, a red boil-like nodule appears at the site of inoculation (Figure 1a). A central crust is formed after two weeks, which may persist as such or fall off, revealing an underlying ulcer (Figure 1b). The ulcer enlarges over the next 2-3 months and the lesion reaches a diameter of 3-6 cm (Figure 1c). Multiple small secondary nodules (satellite lesions), which are about 2-4 mm in size, appear around the lesion (Figure 1d) or along the lymphatics (sporotrichoid pattern) (Figure 1e). Healing follows 2-6 months later leaving a scar [1, 8] (Figure 1f). Anthroponotic CL is acquired from infected humans. After an incubation period of more than 8 weeks, a small brownish nodule appears (Figure 2a), which slowly turns into a plaque, 1-2 cm in diameter, in about six months time (Figure 2b). A shallow ulcer develops in the center with a thin adherent crust. Multiple secondary nodules occur less frequently than in the wet type. The lesion regresses within 8-12 months and the ulcer heals leaving a scar. The average duration of the disease is twice as long as the zoonotic infection [1, 8].

|  |

| Figure 2a | Figure 2b |

|---|---|

| Figure 2a. Initial brownish nodule of dry, urban type of cutaneous leishmaniasis Figure 2b. Plaque lesion of dry, urban type of cutaneous leishmaniasis | |

Clinical classification (depending on pattern, behavior and extent of disease)

The most practical way of categorizing CL is on the basis of clinical features of the disease.

1. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (Figure 3)

|  |

| Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

|---|---|

| Figure 5. Multiple lesions on the face related to sandfly bites at multiple sites Figure 6. Chronic localized cutaneous leishmanisis of face | |

Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (LCL) in the old world is caused by L. major, L. tropica, L. infantum, and L. aethiopica, primarily by the former two. With minor differences, the clinical lesions produced by all these species are similar (Figure 3). Solitary or multiple subcutaneous nodules (smooth, soft, mobile and 0.5-2.0 cm in size) may occur proximal to the skin lesions and usually along the axis between the skin lesions and the regional lymph nodes (Figures 1e and 4). This is called sporotrichoid spread of LCL. Healing usually takes place in 2-6 months in L. major infection and 8-12 months in L. tropica. The healing is almost always with a scar that is typically atrophic, hyperpigmented, and irregular. In some cases cutaneous leishmaniasis has been found to remain “active,” i.e., with positive smears, for 24 months or even longer. Such cases have been designated “non-healing chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis” [6, 8, 9, 10]. Multiple lesions can be seen (Figure 5) and the highest number of lesions reported for a single patient is 425 [11]. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis can be differentiated as acute (< 6 months duration) (Figure 1), chronic (> 6 months duration) (Figure 6) and recidivans (Figure 7). Acute LCL can be further divided into three varieties: nodular-including papules and plaques (Figures 8 and 9), nodulo-ulcerative (Figure 1b), and ulcerative (Figure 10). These forms may appear singly or as an overlap picture. They may show all features described for a classical lesion i.e. clustered lesions, paired lesions (Figures 11 and 12), skin crease orientation, volcanic nodules (Figure 13), satellite papules (Figure 1d), subcutaneous nodules (Figure 4), and iceberg nodules (Figure 14) [6, 9, 12]. Some other uncommon and unusual clinical features of LCL, in addition to the above-mentioned classical picture, are described later in this article.

|  |

| Figure 9 | Figure 10 |

|---|---|

| Figure 9. Erythemato-squamous nodule and plaque over lower lip and cheek Figure 10. A large ulcerative plaque of cutaneous leishmanisis on wrist region | |

|  |

| Figure 11 | Figure 12 |

|---|---|

| Figure 11. Paired lesion (Bilaterally symmetrical) of cutaneous leishmaniasis on arms Figure 12. Bilateral symmetrical lesions on legs | |

2. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (Figures 15 and 16)

|  |

| Figure 15 | Figure 16 |

|---|---|

| Figure 15. Involvement of cutaneous as well as mucosal surfaces of lip and nose in a child Figure 16. Mucocutaneous involvement in an elderly patient | |

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), also called espundia in South America, is a serious and occasionally a life threatening form of leishmaniasis, found mainly in the new world. However, cases showing chronic destructive ulcerative lesions of the nasal cavity and mid face have been seen in the Old World. In the New World, L. braziliensis braziliensis, and in Africa, L. aethiopica, are the most common etiologic agents. In Pakistan we have recently seen few cases of MCL with a benign course and favorable outcome most probably caused by L. tropica. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis starts with a cutaneous lesion that is identical to that of CL. However, rather than showing eventual resolution, the infection extends to the adjacent mucosa and cartilage of the upper respiratory tract. The disease leads to marked disfigurement and patients with mucosal disease never heal spontaneously. Lesions have been seen on the lips and eyelid; the lip appears swollen and the lid scaly. Involvement of the cornea has also been described [9, 10, 13].

3. Diffuse (Anergic) cutaneous leishmaniasis

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) is a polar form of cutaneous leishmaniasis characterized by disseminated nodules, an abundance of parasites throughout the course of the disease, the absence of parasite-specific cell-mediated immune response, and a poor response to antimonial treatment. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis may be caused by L. m. amazonensis, L. mexicana and L. pifanoi in the new world and by L aethiopica in the old world, but the disease caused by L. m. amazonensis in Central and South America is more common. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis related to L. major has also been reported. The disease usually begins with an initial primary lesion, which disseminates to involve other areas of the skin. The lesions are often scattered over limbs, buttocks, and face. These progress slowly and become chronic; the improvement following treatment is gradual and relapse is a rule. There is no systemic involvement. The histology shows macrophages loaded with amastigotes [6, 8, 9, 10].

4. Leishmaniasis recidivans (Figure 7)

Leishmaniasis recidivans (LR) is a distinctive form of chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis that is usually a complication of L. tropica in the old world and less commonly L. braziliensis in South America. LR refers to the development of new lesions in the center or periphery of a healed lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clinically there is a central scar in which central or peripheral infiltrated papules and crusted inflammatory lesions develop. These expand slowly, assuming a circular or arciform configuration. It is also termed relasping leishmaniasis and behaves similar to lupus vulgaris, appearing in the margins of the healed scar. Apple jelly nodules are seen and lesions are slowly growing. The lesions frequently worsen in summer tend to resist treatment. Although not as destructive as lupus vulgaris, leishmaniasis recidivans may persist and spread for many years. The recidivans lesion is the result of a peculiar host reaction in which the cellular immunity fails to sterilize the lesion despite the presence of exaggerated hypersensitivity [6, 8, 9, 10].

5. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (Leishmanid)

Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) is a rare sequel to visceral leishmaniasis that has been apparently cured after adequate treatment. It is caused by L. donovani and L. aethiopica in the old world and is endemic in East Africa and India. In India the rash of PKDL occurs in 20 percent of patients and appears 1-2 years after treatment of the original disease and may persist for as long as 20 years. In Africa, this usually appear during or shortly after treatment and persists only for a few months. Skin lesions are categorized into 3 types, often in sequence: (i) hypopigmented macules markedly similar to the lesions of lepromatous leprosy, (ii) erythematous macules develop, which develop next, and (iii) yellowish pink nodules that finally appear, mostly on the face. These replace the hypopigmented and erythematous macules after a variable period of months or years. The rash is progressive over many years and seldom heals spontaneously. Cases of PKDL are more resistant to treatment, requiring higher doses of systemic medication [6, 8, 9, 10].

6. Viscerotropic leishmaniasis

In the recent past, L. tropica was found to be the causative organism in several cases of visceral leishmaniasis in American soldiers returning from Saudi Arabia and this was named viscerotropic leishmaniasis (VL). The clinical features of VL consist of high-grade fever, malaise, intermittent diarrhea, and abdominal pain; skin lesions do not occur. Skin involvement in visceral leishmaniasis has been poorly documented [9].

Atypical / Unusual Cutaneous leishmaniasis

In addition to the classical clinical picture, several unusual and atypical features of the disease have been reported in the literature. Lesions may appear at unusual sites and in unusual number or the disease may present with atypical morphologies [14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. Many atypical presentations, so far described in the literature are categorized below.

A. Atypical pattern related to unusual sites and number of lesions

Multiple lesions can be seen in LCL, the highest number in one patient was 425 lesions [12]. Similarly, unusual sites can be encountered, which may lead to difficulty in diagnosis. These unusual sites reported include the genital area, penis, eyelids, lips, nostrils, hair-bearing scalp and nipple [14, 15, 16, 17]. Atypical variants according to unusual sites include:

1. Chancriform leishmaniasis (Figure 17)

|  |

| Figure 17 | Figure 18 |

|---|---|

| Figure 17. Chancre like solitary lesion on lower lip Figure 18. Cutaneous leishmaniasis mimicking paronychia | |

Solitary or multiple painless, non-pruritic, indurated chancre-like lesions on lips or glans penis are occasionally seen [14, 15, 18].

2. Paronychial leishmaniasis (Figures 18 and 1e)

Swelling and erythema resembling acute/chronic paronychia are seen around the toes and on the fingers. This rare form was first reported from Pakistan [14, 17].

3. Whitlow leishmaniasis (Figure 19)

This unusual presentation resembling inoculation herpes on the pulp of finger has been twice reported from Pakistan [15, 17].

|  |

| Figure 19 | Figure 20 |

|---|---|

| Figure 19. Lesion on pulp of finger resembling whitlow (inoculation herpes) Figure 20. Cutaneous leishmaniasis of lower eyelid | |

4. Lid leishmaniasis (Figure 20)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions occurring on eyelids and adjoining areas have been rarely described [15, 19].

5. Scalp leishmaniasis

Cutaneous leishmaniasis occurring on hair-bearing scalp is another very rare presentation [18].

6. Scar leishmaniasis (Figure 21)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis appearing in a previous scar of a non-related cutaneous disease (tuberculoid leprosy) was reported from Pakistan for the first time [20].

|  |

| Figure 21 | Figure 22 |

|---|---|

| Figure 21. Cutaneous leishmaniasis occurring in previous healed scar of tuberculoid leprosy Figure 22. Multiple large linear nodular plaques in sporotrichoid array | |

B. Atypical pattern related to unusual morphologies

The unusual morphologies reported for localized cutaneous leishmaniasis include hyperkeratotic psoriasiform lesions, eczematoid lesions, zosteriform pattern, warty lesions, erysipeloid lesions, keloidal and nodular lesions and acneiform lesions [14, 15, 18, 21].

1. Sporotrichoid leishmaniasis (Figures 22 and 1e)

A sporotrichoid pattern is seen as beaded nodules extending from the main lesion along a lymphatic channel. These are painless and do not ulcerate. The amastigotes are seen in the primary but not in secondary lesions. Sporotrichoid nodules are thought to represent an immune reaction from direct lymphatic extension of leishmania antigens or organisms [14, 15, 23, 24].

|  |

| Figure 23 | Figure 24 |

|---|---|

| Figure 23. Erysipelas like lesion on one side of the face Figure 24. Large, heaped up verruciform plaque of cutaneous leishmaniasis | |

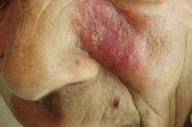

2. Erysipeloid leishmaniasis (Figure 23)

Diffuse erythema and swelling appearing like erysiploid has been seen on the face and arms. Margins may show nodulation or erythema with positive smears for amastigotes [14, 15, 25, 26].

3. Vegetating/Verrucous leishmaniasis (Figure 24)

The presence of secondary infection in the lesions may cause a verroucous appearance which is deceptive and does not resemble the original lesion [15].

4. Tumorous/SCC like leishmaniasis (Figure 25)

|

| Figure 25 |

|---|

| Figure 25. Fungating growth of cutaneous leishmaniasis mimicking squamous cell carcinoma |

Chronic leishmaniasis occasionally mimics squamous cell carcinoma and may be very difficult to diagnose [15].

5. Acneiform leishmaniasis

Acne-like lesions have also been described in the literature but these have not beeb seen in Pakistan [14].

6. Lupoid leishmaniasis (Figures 26 and 27)

|  |

| Figure 26 | Figure 27 |

|---|---|

| Figure 26. Lupoid leishmaniasis involving nose and cheek Figure 27. Diffuse involvement of face in lupoid leishmaniasis | |

The cutaneous lesions on the face resembling those of lupus vulgaris or lupus erythematosis are frequently seen these days in certain regions of Pakistan. These are not chronic cases; previously lupoid leishmaniasis was considered a form of chronic CL and the term was interchangeably used with leishmaniasis recidivans [15].

7. Keloidal leishmaniasis

A lesion of CL may occasionally become a hard nodule and look like a keloid [14].

8. Eczematous leishmaniasis (Figure 28)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis rarely appears as chronic eczematous lesions [21, 22].

|  |

| Figure 28 | Figure 29 |

|---|---|

| Figure 28. Nummular eczema-like lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis on arm Figure 29. Psoriasiform lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis | |

9. Psoriasiform/Hyperkeratotoic leishmaniasis (Figure 29)

Cutaneous leishmaniasis may appear as erythematous scaly lesions of psoriasis or non-psoriasiform hyperkeratotic disease [15, 27].

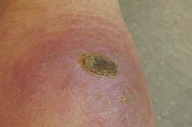

10. Mycetoma-like leishmaniasis (Figure 30)

|

| Figure 30 |

|---|

| Figure 30. Chronic non-healing and discharging lesions resembling mycetoma of the foot |

Chronic infiltrating lesions on the foot that may bear some discharging sinuses to resemble actinomycosis or mycetoma of the foot [15].

11. Annular leishmaniasis

Annular lesions of CL have also been reported in the literature [14].

12. Zosteriform leishmaniasis (Figures 31 and 32)

|  |

| Figure 31 | Figure 32 |

|---|---|

| Figure 31. Closely grouped erythematous papular lesions looking very much like herpes zoster Figure 32. Zosteriform lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis over the back | |

Multiple papules are seen closely arranged in a zosteriform pattern on the trunk. This zoster-like leishmaniasis has been found to occur on the lower extremity and back [15, 28, 29].

13. Palmoplantar leishmaniasis (Figure 33)

Painless, non-pruritic lesions on the palms and soles have probably been described only in cases from Pakistan [14, 15].

|  |

| Figure 33 | Figure 34 |

|---|---|

| Figure 33. Cutaneous leishmaniasis occurring on planter aspect of foot Figure 34. Multiple lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis resembling lesions of DLE | |

14. DLE-like leishmaniasis (Figure 34)

This is another very rare presentation from Pakistan in which lesions morphologically resembling chronic discoid lupus erythematosis were found to be positive for leishmania parasites [15, 18].

15. Rhynophymatous leishmaniasis (Figure 35)

Chronic cutaneous lesions on the nose may present like rhynophyma [30].

16. Fissure leishmaniasis (Figures 36 and 37)

|

| Figure 37 |

|---|

| Figure 37. Cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as vertical fissure on lower lip |

Clinical presentations resembling fissures on the lower lip or on the dorsum of the finger have also been reported [31].

17. Leishmaniasis in HIV positive patients

Co-infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has resulted in the development of atypical forms of visceral leishmaniasis with an increased incidence of cutaneous involvement; skin findings may be the earliest sign of the disease. The reported cutaneous lesions include a psoriasiform eruption, papulonodular lesions, an erythrodermic pattern, linear brown macules, a dermatomyositis-like eruption, and a polymyositis-like syndrome. In addition, leishmania parasites have been identified in biopsies of a fibrous histiocytoma and a skin tattoo. Unusual and aggressive mucosal, muco-cutaneous, diffuse cutaneous, or post-kala-azar leishmaniasis may also be seen in HIV positive patients [6, 8, 10, 32, 33, 34].

Old World CL may be considered a bipolar disease. On one end of the spectrum is the classical self healing sore in which immunity to reinfection is the result of an effective parasiticidal mechanism. However, on the other end of the spectrum is the diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, in which metastatic cutaneous lesions develop and the patient rarely, if at all, spontaneously develops immunity to the parasite [35, 36]. New World CL also exhibits a wide clinical spectrum including localized, disseminated, and mucocutaneous disease. The disease is generally more aggressive and various atypical presentations have also been reported [37, 38]. A wide variety of clinical presentations (both in old and new world disease) presumably caused by a complex interplay between parasite species, various host factors, and immuno-inflammatory responses [36].

Treatment of various forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis

There is no single, widely accepted optimal treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Treatments that work for one species of leishmania and in one geographical area may not work for another species and in another geographical region. So far, the most established treatment, despite its documented toxicities, remains pentavalent antimonial compounds, either given systemically (intramuscular) or locally (intralesional). Other drugs that may be used are miltifosine, amphotericine B, ketoconazole, itraconazole, fluconazole, pentamidine, and paromomycine. A simple guideline to follow is to try the topical or intralesional therapy for the treatment of simple sores and reserve the systemic use of pentavalent antimonials for the more problematic lesions. These would include those occurring over the face or other vital areas in which scarring would be disabling or disfiguring, lesions over cartilage, larger lesions, and disease with lymphatic involvement [2, 6, 28, 39, 40, 41]. Effective treatment options for various forms of disease in Pakistan where disease is most often caused either by L. tropica or L. major are shown in Table 1.

References

1. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med 2003; 49:50-4. [PubMed]2. Markle W, Makhoul K. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Recognition and Treatment. American Family Physician 2004; 69: 6. 1455-60. [PubMed]

3. Bhutto AM, Soomro RA, Nonaka S, Hashiguchi Y. Detection of new endemic areas of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan: a 6-year study. Int J Dermatol 2003;42: 543-8. [PubMed]

4. Rahman SB, Bari AU. A new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2003; 13: 3-6.

5. Khan SJ, Muneeb S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Dermatol Online J. 2005; 11(1): 4. [PubMed]

6. Manzoor A. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2005; 15: 161-71.

7. Ayub S, Khalid M, Mujtaba G, Bhutta RA. Profile of patients of cutaneous Leishmaniasis from Multan. J Pak Med Assoc 2001; 51: 279-81. [PubMed]

8. Lopez FA, Hay RJ. Parasitic worms and protozoa. In: Burns T, Breathnack S, Cox N, Giffiths C. Eds. Rook’s Text of Dermatology. Vol. 2. 7th ed. Blackwell Science Ltd. 2004; 35.32-35.47.

9. Grevelink SA, Lerner EA. Leishmaniasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 34: 257-72. [PubMed]

10. Ghosn SH, Kurban AK. Leishmaniasis and Other Protozoan Infections. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA. Paller AS, Leffell DJ. Eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol. 2, 7th ed. Mcgraw Hill Inc. 2008: 2001-9.

11. Couppie P, Clyti E, Sainte-Marie D, Dedet JP, Carme B, Pradinaud R. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71: 558-60. [PubMed]

12. Kubba R, Al-Gindan Y, El Hassan AM. Clinical diagnosis of cutaneous Leishmaniasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987; 16: 1183-1188. [PubMed]

13. Bari AU, Manzoor A. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Does it really exist in Pakistan? J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2005; 15: 200-3.

14. Raja KM, Khan AA, Hameed A, Rahman SB. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 139: 111-3. [PubMed]

15. Bari AU, Rahman SB. Many faces of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74: 23-7. [PubMed]

16. Rahman SB, Bari AU. Morphological patterns of cutaneous leishmaniasis seen in Pakistan. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2002; 12: 122-9.

17. Iftikhar N, Bari I, Ejaz A. Rare variants of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: whitlow, paronychia, and sporotrichoid. Int J Dermatol. 2003; 42: 807-9. [PubMed]

18. Shamsuddin S, Mengal JA, Gazozai S, Mandokhail ZK, Kasi M, Muhammad M, et al. Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis in native population of Baluchistan. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2006; 16: 196-200.

19. Bari AU, Haq IU, Rani M. Lid Leishmaniasis: An atypical clinical presentation. J Col Phys Surg Pak 2006; 16(11): 725-6. [PubMed]

20. Bari AU, Rahman SB. Scar Leishmaniasis. J Col Phys Surg Pak 2006; 16: 294-5. [PubMed]

21. Manzoor A, Butt UA. Atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis resembling eczema on the foot. Dermtol Online J 2006; 12: 18. [PubMed]

22. Uzun S, Acar MA, Uslular C, Kavukcu H, Aksungur VL, Culha G, et al. Uncommon presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis as eczema-like eruption. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999; 12: 266-8. [PubMed]

23. Nandy A, Choudary A B. Lymphatic Leishmaniasis in India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1988; 82: 411. [PubMed]

24. Momeni AZ, Javaheri AM. Clinical picture of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Isfhan Iran. Int J Dermatol 1994; 33: 260-5. [PubMed]

25. Bari AU, Iftikhar N, Rahman SB. Eryseploid Cutaneous Leishmaniasis; A rare presentation. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2002; 12: 160-1.

26. Karincaoglu Y, Esrefoglu M, Ozcan H. Atypical clinical form of cutaneous leishmaniasis: erysipeloid form. Int J Dermatol. 2004; 43: 827-9. [PubMed]

27. Lahiry A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002; 68:145-6. [PubMed]

28. Rahman SB, Bari AU, Mumtaz N. Miltefosine in cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Col Phys Surg Pak 2007; 17: 132-5. [PubMed]

29. Omidian M, Mapar MA. Chronic Zosteriform cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006; 72: 41-2. [PubMed]

30. Bari AU, Ejaz A. Rhinophymous Leishmaniasis. A new variant. Dermatology Online Journal 2009; 15 (3): 10. [PubMed]

31. Bari AU, Ejaz A. Fissure Leishmaniasis. A new variant of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Dermatology Online Journal 2009; 15 (10): 13. [PubMed]

32. Puig L, Pradinaud R. Leishmania and HIV co-infection: dermatological manifestations. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2003; 97 Suppl 1: 107-114. [PubMed]

33. Bittencourt A, Silva N, Straatmann A, Nunes VL, Follador I, Badaro R. Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis associated with AIDS. Braz J Infect Dis 2003; 7:229-33. [PubMed]

34. Sanchez P, Bosch RJ, de Galvez MV, Rodrigo AB, Herrera E. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in a patient with the human immunodeficiency virus. Int J STD AIDS 2001; 12: 687-9. [PubMed]

35. Rahman SB, Bari AU. Cellular immune host response in acute cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Col Phys Surg Pak 2005; 15: 463-6. [PubMed]

36. Bari AU, Rahman SB. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview of parasitology and hosp-parasite-vector interrelationship. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2008; 18: 42-8.

37. Convit J, Ulrich M, Perez M, Hung J, Castillo J, Rojas H, et al. Atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis in Central America: possible interaction between infectious and environmental elements. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2005; 99: 13-17. [PubMed]

38. Calvopina M, Gomez EA, Uezato H, Kato H, Nonaka S, Hashiguchi Y. Atypical clinical variants in New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: Disseminated, Erysipeloid and Recidivia cutis due to Leishmania panamensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73: 281-4. [PubMed]

39. Bari AU, Rahman SB. Therapeutic Update on Cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Col Physicians Surg Pak 2003; 13 (8): 471-6. [PubMed]

40. Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007; 7(9): 581-96. [PubMed]

41. Ameen M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: therapeutic strategies and future directions. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007; 8(16): 2689-99. [PubMed]

© 2012 Dermatology Online Journal