Two cases of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis related to oral terbinafine and an analysis of the clinical reaction pattern

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D38cr0t2khMain Content

Two cases of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis related to oral terbinafine and an analysis of the clinical reaction

pattern

Jennifer T Eyler1 BS, Stephen Squires2 MD, Garth R Fraga3 MD, Deede Liu2 MD, Thelda Kestenbaum2 MD

Dermatology Online Journal 18 (11): 5

1. University of Kansas School of Medicine2. Department of Dermatology, University of Kansas Medical Center

3. Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Kansas Medical Center

Abstract

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a clinical reaction pattern characterized by the rapid appearance of widespread sterile, nonfollicular pustules arising within edematous erythematous skin. This aseptic pustular eruption is commonly accompanied by leukocytosis and fever and usually follows recent administration of oral or parenteral drugs. We report two cases of terbinafine-induced AGEP in male patients. Both patients developed a generalized erythroderma with scaling and pruritic pustules 7 and 14 days following initiation of oral terbinafine. With immediate discontinuation of terbinafine and various treatment protocols, both patients demonstrated recovery followed by skin desquamation during the subsequent weeks. Terbinafine is the most frequently used systemic antimycotic and antifungal medication, reflecting its superior efficacy for dermatophyte infections. Despite the appealing drug profile, an awareness of terbinafine-induced AGEP is important given the 5 percent mortality associated with AGEP. Additionally, distinguishing the characteristics of AGEP from those associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and generalized pustular psoriasis allows for prompt dermatologic evaluation, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment.

Introduction

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a clinical reaction pattern characterized by rapid occurrence of widespread sterile, nonfollicular pustules arising within edematous erythematous skin and accompanied by leukocytosis and fever [1]. AGEP usually follows recent administration of oral or parental drugs, most commonly antibiotics [2,3]. The acute pustular reaction usually spontaneously resolves within 10 days following drug termination, followed by desquamation of the skin [2].

AGEP was first described by Macmillan in 1973 as “drug-induced generalized pustular rash” [4]. In 1980, Beylot et al introduced the term AGEP and described specific clinical criteria of an acute rash in individuals with no history of psoriasis, occurrence after an infection or use of drugs, and spontaneous remission. The histologic criteria included vasculitis associated with non-follicular subcorneal pustules [5]. In 1991 Roujeau et al. performed a retrospective study of 63 cases and suggested five criteria for defining AGEP: (1) numerous, small, mostly non-follicular pustules on a widespread edematous erythema; (2) pathologic study showing intraepidermal or subcorneal pustules associated with 1 or more of the following: dermal edema, vasculitis, perivascular eosinophils, focal necrosis of keratinocytes; (3) fever > 38°C; (4) blood neutrophil count > 7 × 109/L (7 K/µL); and (5) acute evolution with spontaneous resolution of pustules in less than 15 days [6].

We report two cases of terbinafine-induced AGEP in male patients. Both patients developed a generalized erythroderma with scaling and pruritic pustules 7 and 14 days following initiation of oral terbinafine. The clinical course for each patient incorporated a slightly different treatment regimen and showed a positive outcome with improvement at varying rates over the next several weeks.

Case reports

Case 1

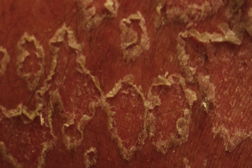

|

| Figure 1 |

|---|

A 42-year-old male with a long history of plaque psoriasis presented to the dermatology clinic with a severely painful scaling rash from head to dorsal feet, sparing only the palms and soles. The patient had recently been prescribed oral terbinafine for suspected tinea unguium of the fingernails. He was taking no other prescription drugs or supplements and denied illicit drug use. After fourteen days of terbinafine treatment, the patient experienced a warm burning sensation over his entire body and immediately discontinued the drug. One day later, the patient developed chills and a generalized erythematous rash sparing his feet and hands. He was admitted to the hospital and subsequently transferred to the burn unit for suspected toxic epidermal necrolysis. The patient was afebrile (36.6°C) with a leukocytosis of 38.1 x 109/L (38.1 K/µL) on admission. On physical examination, there was generalized erythroderma with numerous small yellow pustules surrounded by patches of dry silvery scale. There was no notable mucous membrane involvement. The Nikolsky sign was negative.

The differential diagnosis included AGEP related to terbinafine and pustular psoriasis. Skin shave biopsy demonstrated pustular dermatitis with eosinophils, favoring AGEP. The patient was started on oral hydroxyzine for symptom management, triamcinolone 0.1 percent ointment applied twice daily to the trunk and extremities under occlusion, and desonide ointment applied twice daily to his scalp and face. The pustulation and scaling markedly improved within 48 hours and completely resolved within a week using topical steroids. The patient was instructed to avoid oral and topical terbinafine.

Case 2

|

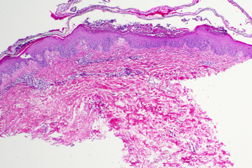

| Figure 2 |

|---|

A 38-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department fourteen days after developing a progressively worsening rash on his trunk and extremities. The rash began seven days after taking oral terbinafine for suspected tinea pedis. It commenced on the lower back as pruritic and slightly tender erythematous plaques with small white pustules prompting the patient to immediately discontinue his oral terbinafine. Within 24 hours the erythematous patches had become more painful, grown in size, and spread to the patient’s upper back, chest, abdomen, groin, and extremities. The patient immediately saw his primary care physician who initiated oral prednisone 40 mg daily. With no improvement after three days of prednisone treatment, the dose was increased to 80 mg orally daily. The rash continued to progress for an additional three days, at which point the patient was prescribed oral Keflex. Two days later while traveling for business, the patient awoke in extreme pain and sought urgent medical care. He was clinically diagnosed with Stevens-Johnson syndrome at an outside institution with instructions to obtain emergency care.

|  |

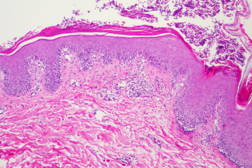

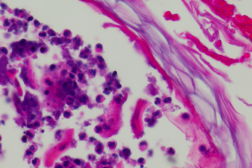

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|

|

| Figure 5 |

|---|

On initial presentation in the emergency department, the patient was afebrile (36.8°C) with a leukocytosis of 23.6 x 109/L (23.6 K/uL). Physical exam revealed widespread erythema with diffuse desquamation and small pustules from scalp to ankles. There was no mucous membrane involvement. The patient’s hands were notably edematous. He denied fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. The differential included AGEP, pustular psoriasis, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). A punch biopsy of the skin revealed pustular dermatitis. Although the histopathologic differential included both AGEP and pustular psoriasis, the timing of the eruption and absence of a personal history of psoriasis suggested AGEP secondary to terbinafine. The patient was treated with intravenous Solumedrol for 3 days, topical Aquaphor, diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine as needed for symptom control, and oral oxycodone as needed for pain. Improvement was noted after two days with decreased swelling and no additional pustules. The patient was discharged home on an oral steroid taper and instructed to avoid oral and topical terbinafine.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of AGEP includes generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular erythema multiforme, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, bullous impetigo, and pustular vasculitis [2]. A skin biopsy is valuable in differentiating between the above diagnoses. GPP can appear clinically and histologically indistinguishable from AGEP. However, AGEP is typically defined by a single episode and self-limiting clinical course, whereas the skin reaction of GPP lasts longer and often recurs (Table 1) [7]. Absence of personal or family history of psoriasis, absence of conventional psoriatic features, and demonstration of eosinophils on biopsy favors AGEP [8]. Of note, our first patient had a personal history of psoriasis whereas our second patient had no significant dermatologic history. Coquart et al. made an argument for the association of AGEP with psoriasis by presenting a psoriatic patient with four recurrences of AGEP [3]. The correlation between psoriasis and AGEP is still debated, with evidence to both support and contradict the distinction. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis can also closely resemble AGEP. However, it is usually associated with monoclonal gammopathy (IgA) and multiple myeloma. It produces annular and polycyclic plaques with peripheral pustulation and a predilection for flexural skin.

Over 90 percent of AGEP cases are induced by systemic drugs [9]. The EuroSCAR multinational case-control study found the following drugs to be highly associated with AGEP: pristamycin, aminopenicillins, quinolones, antimalarials, sulphonamides, diltiazem, and terbinafine [1]. Additionally, EuroSCAR noted that drugs most commonly associated with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are not associated with AGEP. In conclusion, EuroSCAR confirmed the predominant association of drugs with AGEP and the minimal connection of AGEP to infections; EuroSCAR strongly suggested that AGEP is unrelated to a personal or family history of psoriasis [1].

The chronological relationship between drug administration and AGEP onset is conveyed through two different patterns. Cases of AGEP induced by antibiotics typically occur in a very short time span of less than 2 days after administration of the suspect drug. The EuroSCAR multinational study reported a mean time span of 1 day after initial antibiotic administration [5]. For most other drugs, the median onset of skin reaction following drug administration is 11 days [1]. Terbinafine is the most common antifungal associated with AGEP. Terbinafine-induced AGEP has a latency period ranging from 2 to 44 days [9]. Our two cases demonstrated an onset of AGEP secondary to terbinafine treatment averaging 10.5 days.

Both of our patients met all of Roujeau’s clinical criteria for diagnosing AGEP except temperature > 38°C. Both patients were afebrile on initial presentation and throughout the course of their hospitalization. Several case reports we reviewed mentioned a febrile state on presentation of the patient. Only three case reports mentioning febrile patients cited specific temperatures in the literature of 38.8°C, 38.8°C, and 38.9°C. Two case reports never addressed patient temperature. A study of a 64-year-old female reported that at no time during the duration of the eruption was the patient febrile [2], similar to both of our patients. Because oral terbinafine appears to have a slower onset of reaction (2-44 days) in comparison to antibacterial medications (less than 2 days), the lack of fever in some patients with terbinafine-induced AGEP may reflect the latency period prior to skin eruption, drug termination, or delayed presentation of the patient to a medical facility. Therefore, whereas elevated temperature is currently one of the major criteria for diagnosing AGEP, a lack of fever in patients at the time of presentation does not exclude the diagnosis.

The most important aspect in management of AGEP is immediate withdrawal of the inciting drug [2]. The disease is self-limiting, with fever and pustules abating after 10-15 days followed by desquamation [1, 10]. A 2006 study demonstrated the ability of oral steroid use in conjunction with terbinafine to prolong the pustular eruption beyond 15 days. Our second patient showed a worsening pustular eruption after oral steroid ingestion, but improvement with IV steroids. To date, the therapeutic value of glucocorticoids in management of AGEP remains questionable [11]. Prompt terbinafine discontinuation remains the primary treatment for terbinafine-induced AGEP.

Terbinafine is a member of the allylamine class of antifungal agents effective in treatment of dermatophyte infections [2]. With its once-daily dosing, terbinafine remains the best treatment option for individuals with multiple co-morbidities taking other prescription medications because of its minimal drug-drug interactions [12]. Terbinafine does not interact with cytochrome P-450 enzymes and thus will not produce clinically significant reactions with drugs metabolized by these enzymes.

A postmarketing surveillance study showed the most common side effects of terbinafine to be gastrointestinal, such as nausea and diarrhea, and dermatological events, such as rash, pruritus, and eczema. Cutaneous adverse effects have been reported to occur in 1-3 percent of patients taking terbinafine, with the majority being mild to moderate macular exanthems [13]. The incidence of serious side effects is only 0.04 percent and includes AGEP, subacute cutaneous lupus, and erythema multiforme [12]. Patients with a prior diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus have been cited to develop both erythema multiforme and subacute cutaneous lupus from terbinafine treatment [14]. A 2001 case study presented five patients with induction of subacute cutaneous lupus while taking terbinafine for onychomycosis [15]. This study supported the safety of terbinafine, but affirmed a predisposition to drug-induced or drug-exacerbated disease in patients with known lupus erythematosus or photosensitivity. Despite the risks, oral terbinafine has been approved for onychomycosis for twenty years and still remains one of the most accepted therapies available today.

In conclusion, we recommend that primary care physicians include AGEP in their differential diagnosis with oral terbinafine reactions. Awareness of AGEP leads to more prompt diagnosis and appropriate patient care. This allows for immediate drug cessation and avoidance of the use of oral glucocorticoids, which can sometimes exacerbate or prolong the eruption. A 1999 population-based study recommended immediate dermatologic evaluation with hospitalization deemed necessary in only the most severe presentations [16]. Other comorbidities and medications should be considered when evaluating patients for hospital admission. Given the 5 percent mortality associated in patients with AGEP [17], we also strongly endorse dermatologic consultation for diagnosis, treatment and management.

References

1. Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)-results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol. 2007 Nov;157(5):989-96. [PubMed]2. Hall A, Tate B. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with oral terbinafine. Aust J Dermatol. 2000 Feb;41(1):42-5. [PubMed]

3. Coquart B, Kupfer-Bessaguet I, Staroz F, Plantin P. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) induced by terbinafine and two different antibiotics: four recurrences. Eur J Dermatol. 2010 Sep-Oct;20(5):638-9. [PubMed]

4. Macmillan AL. Generalized pustular drug rash. Dermatologica. 1973;146(5):285-91. [PubMed]

5. Beylot C, Bioulac P, Doutre MS. Pustuloses exanthematiques aigues generalisees. A propos de 4 cas. Ann. Derm. Venereol. 1980 Jan-Feb;107(1-2):37-48. [PubMed]

6. Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. AGEP. Analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1991 Sep;127(9):1333-8. [PubMed]

7. Belda Junior W, Ferolla A. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Case report. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo. 2005 May-Jun;47(3):171-6. [PubMed]

8. Duckworth L, Maheshwari MB, Thomson MA. A diagnostic challenge: acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis or pustular psoriasis due to terbinafine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 37(1):24-7. [PubMed]

9. Beltraminelli HS, Lerch M, Arnold A, Bircher AJ, Haeusermann P. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by the antifungal terbinafine: case report and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2005 Apr;152:780-83. [PubMed]

10. Criton S, Sofia B. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Ind J Dermatol. 2001 Mar-Apr;67(2):93-5. [PubMed]

11. Bajaj V, Simpson N. Oral corticosteroids did not prevent AGEP due to terbinafine. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(5):448-9. [PubMed]

12. Van Duyn Graham L, Elewski B. Recent updates in oral terbinafine: its use in onychomycosis and tinea capitis in the US. Mycoses. 2011 Nov;54(6):e679-85. [PubMed]

13. Bennett M, Jorizzo J, White W. Generalized pustular eruptions associated with oral terbinafine. Int J Dermatol. 1999 Aug;38(8):596-600. [PubMed]

14. Hall M, Monka C, Krupp P, O’Sullivan D. Safety of oral terbinafine: results of a postmarketing surveillance study in 25,884 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1997 Oct;133(10):1213-9. [PubMed]

15. Callen J, Hughes A, Kulp-Shorten C. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced or exacerbated by terbinafine. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Sep;137(9):1196-8. [PubMed]

16. Castellsague J, Garcia-Rodriguez L, Duque A, Perez S. Risk of serious skin disorders among users of oral antifungals: a populations based study. BMC Dermatol. 2002 Nov;2:14. [PubMed]

17. Roujeau JC. Clinical heterogeneity of drug hypersensitivity. Tox. 2005 Apr; 209(2):123-129. [PubMed]

© 2012 Dermatology Online Journal