Cryptococcal meningitis with an antecedent cutaneous Cryptococcal lesion

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D388456934Main Content

Cryptococcal meningitis with an antecedent cutaneous Cryptococcal lesion

Ragini Tilak1, Pradyot Prakash1, Chaitanya Nigam1, Vijai Tilak2, I S Gambhir3, A K Gulati1

Dermatology Online Journal 15 (9): 12

1. Department of Microbiology2. Department of Pathology

3. Department of Medicine

Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. raginijain29@rediffmail.com

Abstract

Cutaneous cryptococcosis, caused by an encapsulated yeast, Cryptococcus neoformans, is generally associated with concomitant systemic infection. Here we report a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis with spread to central nervous system in an HIV seronegative young boy. In the present case, a 17-year-old boy who was suffering from a non-healing ulcer on his right great toe for 5 months, presented with the signs and symptoms of meningitis. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii was isolated from the CSF of the patient. Amphotericin B administration produced recovery from the meningitis as well as from the ulcer. This case study suggests that primary cutaneous cryptococcosis can be diagnosed provisionally by a simple Gram stained smear and India ink examination in order to avoid occurrence of disseminated cryptococcosis, including meningial involvement, which may have a fatal outcome.

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans causes human infection ranging from asymptomatic primary colonization to life-threatening meningitis to overwhelming cryptococcosis particularly in HIV/AIDS patients or other immunocompromised individuals. C. neoformans is an encapsulated heterobasidiomycetous fungus. Traditionally, C. neoformans is classified into two varieties and five serotypes (A, B, C, D, AD) based on its capsule structure [1]. C. neoformans types differ in their natural habitat and geographical distribution. C. neoformans var. neoformans has been isolated from soil contaminated with pigeon or other bird droppings whereas C. neoformans var. gattii has been frequently isolated from decaying wood in the red gum group of Eucalyptus tree. Inhaling the fungus, which is primarily found in soil enriched with pigeon droppings, is the usual mode of infection in humans [2]. In a susceptible host, the fungus can either produce latent infection or acute disease depending on immunity of the host or virulence of the strain [3, 4].

Case report

A 17-year-old boy was admitted to the emergency room in October 2008 with a history of fever of 1½ month's duration, vomiting, seizures, and altered consciousness for last 5 days; a non-healing ulcer on the dorsum of right great toe had been present for five months. The boil-like lesion on the dorsum of his right great toe had been incised and drained at another health center. A course of antibiotics was administered empirically. However, the lesion did not heal and becameulcerated (Fig. 1).

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Non-healing ulcer on right great toe Figure 2. India ink preparation of CSF showing capsulated & budding yeast (x400) | |

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

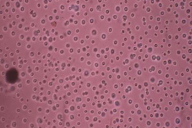

| Figure 3. Gram-positive spherical budding yeast cells in skin ulcer (x1000) |

During the examination, altered higher mental functions and slurred speech were noted. Other parameters were within normal limits. Random blood sugar was 104.8 mg/dL and blood urea was 33.2 mg/dL. Chest X-Ray PA view was normal. Mantoux test for Tuberculosis and Parachek test for malarial parasite were negative. Sputum, blood and urine culture did not reveal any bacterial pathogens. He was seronegative for HIV-I / HIV-2. His CD4 count was 428 cells/μl. On Examination of CSF, cell count showed lymphocytic predominance (80%) with glucose 29 mg/dl and protein 40 mg/dl. CSF India ink examination showed encapsulated yeast cells (Fig. 2). CSF culture on Sabouraud's Dextrose agar showed smooth creamy white mucoid colonies after 48 hours of incubation. A smear from these colonies showed Gram-positive spherical budding yeast cells. Based on the morphology on India ink and Gram staining, the isolate was provisionally identified as an encapsulated yeast. This was further confirmed as Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii using standard biochemical tests. Scraping from the non-healing ulcer revealed Gram-positive yeast cells on Gram staining (Fig. 3) and encapsulated yeast were observed on India ink preparation. Thus, a diagnosis of Cryptococcal meningitis with primary cutaneous cryptococcosis was made. Amphotericin B was started immediately. After 4 days of treatment, his fever subsided, and the patient regained consciousness; the ulcer on the great toe started showing signs of healing. Treatment was continued for a further 10 days. The patient was discharged and oal fluconazole 400mg/day for the next 3 months was given.

Discussion

Cryptococcal meningitis occurs in those HIV seronegative individuals who are immunodeficient due to diabetes, cancer, solid organ transplants, chemotherapeutic drugs, hematological malignancies, and, rarely, in healthy individuals without any obvious predisposing factors. Cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii, in immunocompetent patients is a rare manifestation of the disease [5]. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is a rare occurrence; skin lesions are generally accompanied by systemic infection. Secondary involvement of skin occurs in about 10 percent to 20 percent of cases [6, 7, 8]. It can produce non-specific lesions and may sometimes be the first sign of infection. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can occur from local inoculation or dissemination from a distant site [9]. Primary cutaneous infection usually presents as a solitary lesion on uncovered parts accompanied by regional lymph node involvement, whereas secondary cutaneous infection usually presents with multiple lesions on covered parts, multicentric skin involvement, and deep dermal or subcutaneous lesions. Serotypes A, D, and AD hybrids are globally responsible for 98 percent of all cryptococcal infections in patients with AIDS. Serotypes B and C predominantly affect immunocompetent individuals, but have also been recently reported in patients with AIDS [10]. Gugnani et al. studied 57 clinical isolates of cryptococci from several regions of India, 51 of which were C. neoformans var. grubii, one was C. neoformans var. neoformans and five were C. neoformans var. gattii. Weathered pigeon droppings commonly contain C. neoformans var. neoformans and litter around the trees of the species Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus terreticornis contains Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. In another study Gugnani et al. isolated C. neoformans var. gattii and C. neoformans var. grubii from the flowers and bark of eucalyptus trees in India [11]. In a similar study, an association was found between the distribution of E. camaldulensis and human cryptococcosis cases caused by C. neoformans var. gattii in northern India [12]. Further, C. neoformans var gattii has also been isolated from the decaying wood inside trunk hollows of Syzygium cumini trees (Java plum, Indian black berry) from northwestern India [13].

In the present case the solitary lesion present on the dorsum of the right great toe was not associated with inguinal lymphadenopathy nor abnormal lung findings. Hence, infection may have occurred by direct inoculation of the organism at the site of injury or trauma, although the patient did not provide any history of trauma at the site. Revenga F. et al. reported a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a 46-year-old immunocompetent male. Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans was isolated from the skin as well as from a metallic object [14]. Zorman J.V. et al. reported a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient. The recipient failed to respond to an empirical antibiotic for presumed bacterial cellulitis. The case report indicated that primary cutaneous cryptococcosis must be included in the differential diagnosis of severe cellulitis in solid organ transplant recipients not responding to broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens. In such cases, prompt diagnosis and treatment could dramatically modify the outcome [15].

To the best of our knowledge, the present case is the first case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii in an immunocompetent patient from North India and has rarely been reported elsewhere [5]. Our patient began responding to Amphotericin B and had a gradual recovery with no neurological sequelae. Further, the ulcer showed healthy granulation tissue after a fortnight. Hence, the cases of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis may be diagnosed provisionally by a simple Gram stained smear and India ink examination in order to avoid the occurrence of disseminated cryptococcosis including meningial involvement, which may have a fatal outcome.

References

1. Satishchandra P, Mathew T, Gadre G et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: Clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic overviews 2007; 55: 226-232 [PubMed]2. Subramanian S, Mathai D. Clinical manifestations and management of Cryptococcal infection. J Post grad Med 2005; 51: 21-26 [PubMed]

3. Levitz SM. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev Infect Dis 1991; 13: 1163-1169 [PubMed]

4. Hussain S, Wagener MW, and Singh N. Cryptococcus neoformans infection in organ transplant recipients: variables influencing clinical characteristics and outcome. Emerg Inf Diseases 2001; 7: 375-381 [PubMed]

5. Dora JM, Kelbert S, Deutschendorf C, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus gattii in immunocompetent hosts: case report and review. Mycopathologia 2006; 16: 235-238 [PubMed]

6. Tessari G, Barba A, Lanzafame M, et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a HIV infected patient: case report. J Euro Acad Dermatol and Venereol 1995; 5: 126-126 DOI: 10.1016/0926-9959(95) 96271-9

7. Vasanthi S, Padmavathy BK, Gopal R, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis among HIV infected patients. Indian J Med Microbiol 2002; 20:165-166 [PubMed]

8. Capoor M. R., Khanna G., Malhotra R., et al. Disseminated cryptococcosis with necrotizing fasciitis in an apparently immunocompetent host: a case report. 2008; 46:269-273 [PubMed]

9. Christianson J.C., Engber W., Andes D. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Med Mycol .2003; 41:177-88 [PubMed]

10. Jain N, Wickes BL, Keller SM et al. Molecular epidemiology of clinical Cryptococcus strains from India. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43: 5733-5742 [PubMed]

11. Gugnani HC, Mitchell TG, Litvintseva AP et al. Isolation of Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii from the flowers and bark of Eucalyptus trees in India. Med Mycol 2005; 43:565-569 [PubMed]

12. Chakrabarti A; Jatana M; Kumar P et al. Isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from Eucalyptus camaldulensis in India. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:3340-3342 [PubMed]

13. Randhawa HS, Kowshik T, Preeti Sinha K et al. Distribution of Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans in decayed trunk wood of Syzygium cumini trees in north-western India. Med Mycol 2006; 44:623-630 [PubMed]

14. Revenga F, Paricio JF, Merino FJ et al. Primary Cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent host: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology 2002; 204:145-149 [PubMed]

15. Zorman J.V., Zupanc T.L., Parac Z. et al. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses 2009 [PubMed]

© 2009 Dermatology Online Journal