Complete regression of melanoma associated with vitiligo

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D37sn7h2j7Main Content

Complete regression of melanoma associated with vitiligo

Enric Piqué-Duran, Santiago Palacios-Llopis, MªSol Martínez-Martín, Juan A Pérez-Cejudo

Dermatology Online Journal 17 (1): 4

Department of Dermatology – Dr Jose Molina Orosa Hospital of Lanzarote and Department of Pathology – Dr Jose Molina Orosa

Hospital of LanzaroteArrecife, Lanzarote, Spain. epiqued@medynet.com

Abstract

A 53-year-old woman presented with vitiligo. A pigmented lesion was disclosed in the physical examination. Its histopathologic study showed the presence of a band of melanophages in an uneven distribution. Fibroplasia and telangiectasias were also observed, but neither nevus nor melanoma cells were found. A short time afterwards, the patient developed a metastasis in an inguinal lymph node. In spite of high-dose interferon treatment, the patient died two years after the diagnosis. This case associates two uncommon events: a) the whole regression of a melanoma and b) vitiligo associated with melanoma. Although both processes have a similar pathogenic mechanism, this association is exceptional and probably influences the prognosis.

Introduction

Despite the fact that vitiligo and regression of melanoma may share the same pathogenic mechanisms, the association of both events is rare. Both conditions are effective in destroying melanocytes. Whereas vitiligo in a patient with melanoma usually implies metastatic disease, these patients have a better prognosis than melanoma patients at the same tumoral stage; regression in melanoma seems to be associated with a worse prognosis.

We report on a case in which the appearance of vitiligo heralded a completely regressed melanoma.

Case report

A 53-year-old woman presented with well-defined white patches distributed on the cheeks, chin, neck and sternal area for four months, corresponding to vitiligo (Figure 1). Clinical images of this alteration have been published elsewhere [1].

In addition to vitiligo lesions, a complete examination disclosed a black papule surrounded by a well-defined but irregular, reticular, pigmented patch of 1.2 x 0.7 cm in diameter, located in the lower part of her right leg (Figure 2). The rest of examination was normal.

During questioning the patient stated that the last lesion appeared four years before and it had not changed.

|  |

| Figure 5 | Figure 6 |

|---|---|

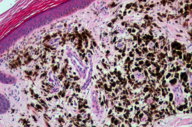

| Figure 5. Detail of Figure 3 in which the atrophy of the epidermis and the telangiectasias are more apparent. Figure 6. Panoramic view: fibroplasia lacking melanophages is evident. | |

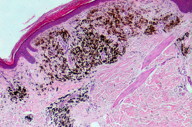

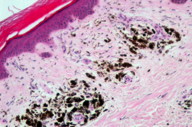

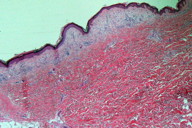

A biopsy of the pigmented lesion showed a flattened and atrophic epidermis. The papilar dermis was thicker than normal and, in some areas, contained a large number of melanophages distributed in an irregular band along the lesion (Figures 3 through 5). Other areas showed regression with no melanin (Figure 6). There was a grenz zone between the melanophages and the epidermis where the presence of fibroplasia (Figure 4) and telangiectasia was evident. Although deeper cuts were done, no melanoma cells were identified. S100 and HMB45 immunochemistry studies failed to demonstrate melanoma cells.

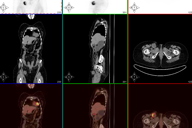

Shortly afterwards the patient developed a hard inguinal node adherent to deep tissue. An abdominal ecography, an abdominal tomography and a PET demonstrated only an inguinal node (Figure 7). LDH was within normal limits.

A lymphedectomy was done disclosing 2 out of 11 metastatic lymph nodes. The patient was diagnosed with melanoma IIIB (Tx N2b M0) with complete regression of the primary lesion associated with vitiligo related to melanoma.

She received high-dose interferon therapy in another center, but unfortunately died two years later as a result of the melanoma.

Discussion

There are different types of leukodermas associated with melanoma. These include a white halo surrounding the primary lesion, white areas intermingled with the melanoma, Sutton halonevus, and achromic patches located in the melanoma scar or in the injection points of immunotherapy [2, 3]. The rarest manifestation is white patches distant from the primary lesion resembling vitiligo.

Some authors consider these patches different from true vitiligo on the basis of some epidemiologic differences, the lack of family history, and some doubtful clinicopathological findings [2]. We believe that these events, true vitiligo, regression of melanoma, and vitilgo-like lesions associated with melanoma are caused by a similar autoimmune mechanism that would destroy melanocytes and/or melanoma cells. The studies of Cui et al [4] and Fishman et al [5] support this theory because they found similar antibody patterns in patients with widespread vitiligo and with metastatic melanomas. Further, the report of Becker et al [6] demonstrated that the lymphocytes of the regression areas of melanomas were the very same as those of nearby hypopigmented areas. In contrast, the study of Merinsky et al [7] found a different pattern of antibodies between true vitiligo and vitiligo associated with melanoma. In our opinion, at present, the only difference between these two is the presence of melanoma in the latter. The association of melanoma with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome has been reported [8] and is probably underdiagnosed. The series of Koh et al [2] found 7 out of 8 cases of ocular involvement associated with vitiligo associated with melanoma. But again, this point is not useful in distinguishing true vitiligo from vitiligo associated with melanoma because ocular alteration has also been described in true vitiligo patients [9].

The incidence of vitiligo associated with melanoma seems to be very low. Thus, Koh et al [2] reported only 8 cases in 14 years in a pigmented lesion clinic. Larger series found an incidence of vitiligo associated with melanoma in melanoma patients of 1.3 percent [10] and 5 percent [11]. Although, the later series found no statistically significant differences when compared with the true vitiligo incidence in the general population. Immunotherapy probably increases the incidence of vitiligo associated with melanoma [12, 13, 14]. On the other hand, a series of 1052 vitiligo patients revealed only 3 cases of melanoma (0.3%), which is a lower incidence of melanoma than in the general population [15].

More important is the significance of vitiligo associated with melanoma in terms of prognosis. Almost all studies demonstrated a higher incidence of metastatic disease in vitiligo associated melanoma patients than patients with melanoma of similar thickness [2, 10, 14, 16, 17, 18]. However, the survival in this subgroup of patients is better than expected according to their melanoma stage [2, 10, 14, 16, 17, 18], probably as a result of a better immunoresponse [19].

The presence of areas of regression are common in melanomas, as demonstrated by McGovern et al [20] who found it in 53 percent of females and in 68 percent of males suffering thin invasive melanomas (≤ 0.7 mm depth). Another series found regression in 16.42 percent of invasive melanomas of ≤ 2 mm depth [21]. The different criteria used to define regression could explain the large differences between both series. Nevertheless, complete regression of a melanoma is a very uncommon event and it is a challenge, because there are no melanoma cells. Ackerman [22] proposed some criteria, used by other authors [23], to reach correct diagnoses in such cases. Thus, lesions > 1 cm in size, with a flattened epidermis that contains some melanocytes of normal appearance. Further, there is neither mucin nor adnexal hyperplasia and the papillary dermis shows a large number of melanophages, so-called nodular melanosis, distributed in an asymmetric fashion, but with a band-like pattern. Our patient fulfilled all these criteria.

Although, in fact it is actually not one of the criteria for staging melanoma, the presence of regression seems to imply a worse prognosis [21, 23, 24]. Thus, Olah et al [20] found 64 percent positive sentinel nodes in melanomas with regression, whereas the sentinel node was positive in only 15 percent of melanomas without regression. Guitart et al [24] found extensive regression in 42 percent of metastatic thin melanomas (< 1 mm), whereas regression was present in only 5 percent of non-metastatic thin melanomas. Although there are no specific studies of prognosis in totally regressed melanoma, according to Ackerman [21], it implies a very bad prognosis. A theory by Prehn [25] may explain this worse prognosis: The melanoma cells that survive the attack of the immune system would be correspondingly more undifferentiated and hence display a more aggressive behavior. However, some recent series failed to demonstrate a worse prognosis in the melanomas with regression [23, 26, 27, 28]. This discrepancy may be caused by different criteria in the selection of patients and in the definition of regression. Thus, in the series by Morris, one patient with an area of regression less than 50 percent of the tumor was included [26] as having regression, whereas the series by Guitart [24] differentiates an extensive regression (> 50%), which was associated with metastasis. Similarly, in the study by Requena [23] there could be a bias because the sentinel node was studied in melanoma < 1 mm with regression, but when the regression was absent, only melanomas > 1 mm were included. Studies with more homogeneous groups and a consensus regarding the concept of regression are needed to resolve the question.

Although we believe that our case cannot be considered a melanoma of unknown primary (MUP) because the patient had a lesion very suspicious for regressed melanoma, it can illustrate one possible etiology for MUP: spontaneous regression of a primary melanoma [29, 30]. Other possibilities are a) a concurrent unrecognized melanoma, b) a previously excised melanoma that was misdiagnosed either clinically or histopathologically, and c) de novo malignant transformation of an aberrant melanocyte within a lymph node [29, 30]. To further complicate the significance of regression on prognosis, the MUP has a better prognosis when compared with same-stage melanomas [29, 30, 31].

To our knowledge, there are no similar cases (total regression of melanoma associated with vitiligo associated melanoma) reported in the literature. Only the report of Arpaia et al [17] is very similar to our case, except that the regression in the Arpaia case was not total. However, some cases of MUP associated with vitiligo associated melanoma have been described [18, 32].

In future work we propose to study the sentinel node in all patients with a totally regressed melanoma (or > 50% of regression) with or without vitiligo associated with melanoma.

References

1. Redondo P, del Olmo J. Images in clinical medicine.Vitiligo and cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med 2008 Jul 17; 359(3): e3. [PubMed]2. Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, Albert DM, Mihm MC, Fitzpatrick TB. Malignant melanoma and *vitiligo*-like leukoderma: An electron microscopic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983; 9: 696-708. [PubMed]

3. Barriere H, Litoux M, Lay L, Bureau B, Stalder JF, Dreno B. Achromies cutanées et melanoma malin- Ann Dermatol Venereol 1984; 111: 991-996. [PubMed]

4. Cui j, Byrstin JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol 1995; 131: 314-318. [PubMed]

5. Fishman P, Merinski O, Baharav E, Schoenfeld Y. Autoantibodies to tyrosinae. The bridge between melanoma and vitiligo. Cancer 1997; 79: 1461-1464. [PubMed]

6. Becker JC, Guldberg P, Zeuthen J, Bröcker EB, Straten PT. Accumalation of identical T cells in melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma. J Invest Dermatol 1999; 113: 1033-1038. [PubMed]

7. Merinsky O, Schoenfeld Y, Yecheskel G, Chaitchik S, Azizi E, Fishman P. Vitiligo and melanoma associated hypopigmentation: a similar appearance but different mechanism. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1994; 38: 411-416. [PubMed]

8. Aisenbrey S, Lüke C, Ayertey HD, Grisanti S, Perniok A, Brunner R. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome associated with cutaneous malignant melanoma: an 11-year follow-up. Graefe’s Arch Clin Ophthalmol 2003; 241: 996-999. [PubMed]

9. Baskan EB, Baykara M, Tunali S, Yucel A. Vitiligo and ocular findings: a study on possible associations. JEADV 2006; 20: 829-833. [PubMed]

10. Byrstin JC, Rigel D, Friedman RJ, Kopf A. Prognostic significance of hypopigmentation in malignant melanoma. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123: 1053-1055. [PubMed]

11. Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, Milton G, Albert DM, Lerner AB. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol 1983; 9: 689-696. [PubMed]

12. Richards JM, Mehta N, Ramming K, Skosey P. Sequential chemoimunotherapy in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1992; 10: 1338-1343. [PubMed]

13. Schebenbogen C, Hunstein W, Keilholz U. Vitiligo-like lesions following immunotherapy with IFN alfa and IL-2 in melanoma patients. Europ J Cancer 1994; 30: 1209-1211. [PubMed]

14. Daneshpazhooh M, Shikoohi A, Dadban A, Raafat J. The course of melanoma-asoociated vitiligo: report of a case. Melanoma Research 2006, 16: 371-373. [PubMed]

15. Lindelöf B, Hedblad MA, Sigurgeirsson B. On association between vitiligo and malignant melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol 1998; 78: 1-2. [PubMed]

16. Duhra P, Ilchyshyn A. Prolonged survival in metastatic malignant melanoma associated with vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991; 16: 303-305. [PubMed]

17. Arpaia N, Cassano N, Vena GA. Regressing cutaneous melanoma and vitiligo-like depigmentation. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45: 952-956. [PubMed]

18. Kiecker F, Hofmann M, Sterry W, Trefzer U. Vitiligo-like depigmentation as presenting sign of metastatic melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol 2006; 20: 1135-1137. [PubMed]

19. Bogunovic D, O’Neill DW, Belitskaya-Levy I, Vacic V, Yu YL, Adams S, Darvishian F, Berman R, Shapiro R, Pavlick AC, Lonardi S, Zavadil J. Immune profile and mitotic index of metastaic melanoma lesions enhance clinical staging in predicting patient survival. PNAS 2009; 106: 20429-20434. [PubMed]

20. McGovern VJ, Shaw HM, Milton GW. Prognosis in patients with thin malignant melanoma: influence of regression. Histopathology 1983; 7: 673-680. [PubMed]

21. Olah J, Gyulai R, Korom I, Varga E, Dobozy A. Tumor regression predicts higher risk of sentinel node involvement in thin cutaneous melanomas. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149: 655-680. [PubMed]

22. Ackerman AB, Briggs PL, Bravo F. Diagnóstico diferencial en dermatopatología III. 1ª ed. Barcelonoa: Edika Med; 1995: 216-219. ISBN 84-7877-116-6

23. Requena C, Botella-Estrada R, Traves V, Nagore E, Almenar S, Guillén C. Regresión en el melanoma: problemas en su definición e implicación pronóstica. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2009; 100: 759-766. [PubMed]

24. Guitart J, Lowe L, Piekorn M, Prieto VG, Rabkin MS, Ronan SG, Shea CR, Tron VA, White W, Barnhill RL. Histological characteristics of metastasizing thin melanomas. A case-control study of 43 cases. Arch Dermatol 2002; 138; 603-608. [PubMed]

25. Prehn RT. The paradoxical association of regressing with a poor prognosis in melanoma contrasted with a good prognosis in keratoacanthoma. Cancer Research 1996; 56: 937-940. [PubMed]

26. Morris KT, Busam KJ, Bero S, Patel A, Brady MS. Primary cutaneous melanoma with regression doesnot require a lower thresfold for sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 316-322. [PubMed]

27. Kaur C, Thomas RJ, Desai N, Green MA, Lowell D, Powell BW, Cook MG. The correlation of regression in primary melanoma with sentinel lymph node status: J Clin Pathol 2008; 61: 297-300. [PubMed]

28. Fontaine D, Parkhill W, Greer W, Walsh N. Partial regression of primary cutaneous melanoma: is there an association with sub-clinical sentinel lymph node metastasis? Am J Dermatopathol 2003; 25: 371-376. [PubMed]

29. Cormier JN, Xing Y, Feng L, Huang X, Davidson L, Gershenwald JE, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Ross MI. Metastatic melanoma to lymph nodes in patients with unknown primary sites. Cancer 2006; 106: 2012-2020. [PubMed]

30. Anbari KK, Schuchter LM, Bucky LP, Mick R, Synnestvedt M, Guerry D, Hamilton R, Halpern AC. Melanoma of unknown primary site. Presentation, treatment, and prognosis – a single institution study. Cancer 1997; 79: 1816-1821. [PubMed]

31. Lee CC, Faries MB, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Imroved survival after lymphadenectomy for nodal metastasis from an unknown primary melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 535-541. [PubMed]

32. Cho EA, Lee MA, Kang H, Lee SD, Kim HO, Park YM. Vitiligo-like depigmentation associated with metastatic melanoma of an unknown origin. Ann Dermatol 2009; 21: 178-181. [PubMed]

© 2011 Dermatology Online Journal