Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Case report and review of literature of a rare entity

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D37111d8sjMain Content

Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Case report and review of literature of a

rare entity

Erich M Gaertner MD 1, Stephen A Switlyk MD2

Dermatology Online Journal 18 (3): 12

1. SaraPath Diagnostics, Sarasota, Florida2. Private Practice, Sarasota, Florida

Abstract

Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with lymphoproliferative disorders is a rare entity, with only 14 cases previously reported in the English literature. Patients generally present with nodules or ulcers involving the extremities, which can appear months or years before or after onset of systemic disease. Granulomatous vasculitis has a poor prognosis when associated with underlying lymphoproliferative disorders, with the majority of reported cases fatal. Knowledge of this unusual entity is important to allow for proper clinical evaluation, follow-up, and therapy. We report a 77-year-old female with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and granulomatous vasculitis, which highlights the features of this association, and expands the clinical data.

Introduction

Granulomatous vasculitis is an uncommon type of vasculitis, manifested by perivascular epithelioid histiocytes and/or multinucleated giant cells, with evidence of vascular damage, generally fibrinoid mural changes and/or hemorrhage. It is usually associated with systemic disease that includes autoimmune disease, inflammatory/granulomatous disease, infections, and rarely lymphoproliferative disorders. The most commonly associated lymphoproliferative disorder is B cell lymphoma, both low and high grade, although T cell lymphoma, leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome have all been reported. Clinical lesions usually involve the extremities, with variable truncal involvement, and can occur concurrently with systemic illness, or months or years before or after. The lesions most commonly present as nodules or ulcers, but can have a variety of clinical appearances, to include purpura, papules, erythema, and vesicles. Paraneoplastic granulomatous vasculitis secondary to underlying lymphoproliferative disease has a poor prognosis, with 9 of the previously reported 14 patients dying of disease. Given the potential lag between the cutaneous lesions and the onset of systemic disease, the possibility of initial misdiagnosis exists, with associated delay in diagnosis and therapy.

Case report

A 77-year-old female with a 3-year history of chronic B cell lymphocytic leukemia was admitted for generalized weakness with occasional falls, new onset shortness of breath, and leg edema. Her last chemotherapy treatment (bendamustine) was several weeks prior, with associated prolonged pancytopenia. Upon admission, the patient was noted to be febrile, with a temperature of 100.3°F, and tachypneic, with a respiratory rate of 20 per minute. Peripheral blood count performed shortly after admission revealed pancytopenia, with a white blood cell count of 1.4 x 109/l with associated neutropenia, hematocrit of 27.4 percent, and platelet count of 68 x 109/l. Peripheral eosinophilia was not present. The patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics that included cefepime and vancomycin, and was transfused 2 units of packed red blood cells which normalized the hematocrit. Chest x-ray was normal.

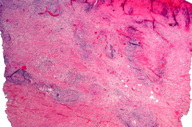

At the time of admission, the patient was noted to have asymptomatic skin lesions involving the upper and lower extremities, manifested by multiple erythematous, indurated nodules, up to 2 cm in greatest dimension (Figure 1). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation and developed central punctuate ulceration. By history, these lesions had been present for three to four weeks. Dermatology consultation was obtained and on dermatoscopic examination, they were noted to have a central violaceous area with erythematous dots, consistent with blood vessels. The initial clinical differential diagnosis included possible leukemia cutis or Sweet syndrome. Cultures and biopsy of a representative skin lesion from the arm was performed. All microbiologic cultures from the skin were negative.

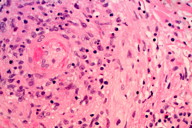

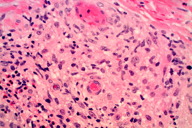

Skin biopsy showed a granulomatous vasculitis with admixed eosinophils. The granulomatous vasculitis was seen throughout the dermis, with involvement of the superficial subcutis (Figure 2), and was manifested by perivascular epithelioid histiocytes and occasional multinucleated giant cells involving small, medium, and large sized blood cells, with focal fibrinoid mural changes, reactive endothelial cells, and hemorrhage (Figures 3 and 4). No lymphomatous skin infiltrate was identified, which was confirmed immunohistochemically. Scattered unremarkable dermal lymphocytes were admixed with the granulomatous vasculitis; these cells were consistent with reactive T cells (CD3 immunohistochemical stain positive) and no significant or atypical B cell infiltrate was identified (CD20 immunohistochemical stain overall negative). Scattered intravascular thrombi were seen in association with the vasculitis in small and intermediate sized blood vessels, with associated ischemic necrosis of the overlying epidermis. No extravascular granulomas were identified. Special stains for infectious organisms (tissue gram stain, acid fast stain for mycobacterium, and Grocott methenamine silver/GMS stain for fungus) were negative. Antinuclear antibody and antineutrophilc cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA and c-ANCA) serologies performed were negative. The patient had no history of asthma or allergic rhinitis.

The patient’s hospital course was relatively uneventful and she steadily improved with intravenous hydration. She was started on prednisone, 60 mg per day, and the cutaneous lesions resolved without scarring. The white blood cell count and neutropenia normalized after two inpatient days. She developed mild watery diarrhea, which also resolved. All microbiologic cultures, from the skin, urine, blood, and stool, were negative for pathogenic organisms. The majority of her admitting systemic clinical symptoms were felt secondary to or exacerbated by poor nutrition; the patient was discharged afebrile with return to baseline health.

Discussion

Cutaneous vasculitis associated with lymphoma is a relatively uncommon paraneoplastic phenomenon and is usually of leukocytoclastic type with associated cyroglobulinemia [1, 2, 3]. Granulomatous vasculitis, defined as a perivascular granulomatous infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes and/or multinucleated giant cells with associated vascular damage is uncommon. It is generally associated with systemic disease including autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome/allergic granulomatosis), inflammatory/granulomatous disorders (sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease), and infections (chronic hepatitis, tuberculosis, leprosy, herpes) [1, 2, 3, 4].

Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with underlying lymphoproliferative disorders is quite rare, with scattered series and case reports. This contrasts with cutaneous involvement by lymphoproliferative disorders with admixed granulomas, often of T cell type, which are well-known. Approximately 14 cases of paraneoplastic cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis associated with underlying hematologic neoplasia have been previously reported in the English language literature. To include the currently reported case, the average reported age is 66 years with a range of 40-77 years and no sex predilection [3-9, current case]. The majority of cases were B cell lymphomas (7 reported with current case) including diffuse large B cell (the most common, including those transformed from low grade lymphomas), diffuse mixed with plasmacytoid differentiation, and low grade lymphocytic. The remaining cases were associated with angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy (2 cases), myelodysplastic syndrome/preleukemia (2 cases, agnogenic myeloid metaplasia and pancytopenia), and single cases of T cell lymphoma, chronic granulocytic leukemia, and lymphoblastic lymphoma (type unspecified) [3-9, current case] In the largest reported series, 7 of 8 patients with granulomatous vasculitis and associated lymphoproliferative disorders died [3], although overall 6 of the 15 reported patients (to include the current) were still alive (either in remission or with continued disease) at the time of publication.

The patients generally presented with cutaneous nodules, ulcers, or purpura, although nonspecific erythema, livedo change, vesicles, papules, and petechiae have all been reported. The lesions most commonly involve the extremities, with variable truncal involvement. They generally occur concomitant with the onset of systemic disease, but can appear months or years before or after the onset of disease. The lesions usually resolve with steroid therapy and/or systemic chemotherapy used to treat the underlying condition. The patients had negative autoimmune serologies, and reported direct immunofluorescence examination performed on selected skin biopsies have shown variable immunoglobulins (predominantly IgM), fibrin, and complement in involved deep and/or superficial vessels. The vasculitis can be localized to the skin, or a component of systemic disease, with some reported cases developing extravascular granulomas, chest x-ray abnormalities, and neuropathies [3].

The reported case highlights this quite rare paraneoplastic phenomenon and expands the known case material and clinical data. The combination of granulomatous vasculitis in a patient with known chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in the absence of any other etiology, fits well with the reported cases. The presence of prominent eosinophilia has been previously reported [3]. Extravascular necrotizing granulomas were not present in the current case. Cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granulomas have been reported in some cases of lymphoproliferative disorder-related paraneoplastic granulomatous vasculitis, but these granulomas lack the characteristic features of those seen in allergic granulomatosis/Churg-Strauss syndrome [3]. Four cases of cutaneous Churg-Strauss granulomas associated with lymphoproliferative disorders (lymphocytic lymphoma, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and low grade lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma) have been reported [10, 11] and a case of intestinal allergic granulomatous angiitis/Churg-Strauss syndrome associated with a fatal retroperitoneal T cell lymphoblastic lymphoma has also been described [12].

As stated, no evidence of an admixed cutaneous lymphomatous infiltrate was present. Rarely drug/medications have been associated with granulomatous vasculitis [13], but no new medications were started at or near the time of onset of the skin lesions; granulomatous vasculitis has not been reported in association with our patient’s medications. The lack of extravascular granulomas with basophilic central necrosis (Churg-Strauss granuloma), peripheral eosinophilia, and associated clinical symptoms (no history of asthma or allergic rhinitis) differentiate the reported entity from allergic granulomatosis/Churg-Strauss syndrome. No infectious organisms were identified on multiple cultures from the skin, blood, urine, and stool, as well as on performed special stains on the skin biopsy. The association of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and paraneoplastic autoimmune syndromes, generally hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and red cell aplasia [14], is well known, but workup (peripheral blood smear review and direct antibody test prior to red blood cell transfusion), showed no evidence of the former. None of these entities has been previously associated with granulomatous vasculitis.

The mechanism for the paraneoplastic granulomatous vasculitis is felt to be secondary to circulating immune complexes and the associated cell-mediated response with granulomatous inflammation. Patients with paraneoplastic granulomatous vasculitis secondary to lymphoproliferative disorders have a generally poor prognosis, with the majority of reported cases fatal. Given skin lesions can occur months or years prior to the onset of systemic symptoms, the possibility of initial misdiagnosis exists. This was highlighted by one reported case initially diagnosed as seronegative Wegener granulomatosis with eventual development of rapidly fatal diffuse large B cell lymphoma [9]. Although rare, recognizing the association of granulomatous vasculitis and underlying lymphoproliferative disorders is important to ensure appropriate clinical evaluation, surveillance, and therapy.

References

1. Wooten M, Jasin H. Vasculitis and lymphoproliferative disorders. Sem Arth Rheum. 1996;24(2):564-574. [PubMed]2. Gibson L, Daniel Su WP. Cutaneous vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995(4): 1097-113. [PubMed]

3. Gibson LE, el-Azhary RA, Smoth TF, et al. The spectrum of cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis: Histopathologic report of eight cases with clinical correlation. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21(5):437-445. [PubMed]

4. Gibson LE, Winkelman RK. Cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis: its relationship to systemic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(3):492-501. [PubMed]

5. Snow JL, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis associated with herpes virus infection: a persistent, painful, postherpetic popular eruption. Mayo Clin Proc 1997;72:851-853. [PubMed]

6. Astudillo L, Recher C, Launay F. Malignant lymphoma presenting as a cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis. Brit J Dermatol. 2005;152(4):820-821. [PubMed]

7. Foley JF, Linder J, Koh J, et al. Cutaneous necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis with evolution to T cell lymphoma. Am J Med 1987;82:839-844. [PubMed]

8. Kwan J, Trafeli J, DeRenzo D. Abdominal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting in association with cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008; 58(5): S93-.95. [PubMed]

9. Cohen Y, Amir G, Schib, et al. Rapidly progressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with initial clinical presentation mimicking seronegative Wegener’s granulomatosis. Eur J Haematol. 2004; 73(2):134-138. [PubMed]

10. Finan MC, Winkleman RK. The cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma (Churg-Strauss granuloma) and systemic disease: A review of 27 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983; 62:142-158. [PubMed]

11. Calonje JE, Greaves MW. Cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma (Churg-Strauss) as a paraneoplastic manifestation of non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphoma. J Royal Soc Med. 1993. Sept (86):549-550. [PubMed]

12. Vougiouklakis T, Mitselou A, Agnatis NJ. Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatous angiitis) associated with T lymphoblastic lymphoma. In Vivo 2004;18(4):477-479. [PubMed]

13. Eeckhout E, Willemsen M, Deconinck A, et al. Granulomatous vasculitis as a complication of potassium iodine treatment for Sweet’s syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol 187;67:362-364. [PubMed]

14. Diehl LF, Ketchum LH. Autoimmune disease and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: autoimmune hemolytic anemia, pure red cell aplasia, and autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Semin Oncol. 1998;25(1):80-97. [PubMed]

© 2012 Dermatology Online Journal