Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D36xz7x91xMain Content

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Ângela Puccini Moreira MD, Flávia Sousa Feijó MD, Jane Marcy Neffá Pinto MD, Isabella Loureiro Martinelli MD, Mayra Carrijo

Rochael MD

Dermatology Online Journal 15 (1): 7

Universidade Federal Fluminense, Hospital Universitário Antônio Pedro – Serviço de Dermatologia. Niterói, Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil. angelapuccini@bol.com.brAbstract

A 55-year-old man with progressive loss of vision was referred for dermatology consultation for the evaluation of his skin lesions. The cutaneous examination of the patient revealed multiple small yellow papules, coalescing into plaques, on his neck, axillae and periumbilical regions. He also had redundant skin folds on the axillae. His peripheral pulses and blood pressure were normal. Angioid streaks were found in the ocular fundi. A skin biopsy specimen of the papule showed fragmentation of elastic fibers as well as calcification in the dermis. Given the clinical manifestations and the histopathologic findings, the patient's illness was diagnosed as pseudoxanthoma elasticum. The patient was then sent to undergo a thorough cardiovascular evaluation.

Introduction

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) or Grönblad-Strandberg syndrome is an inherited multisystem disorder primarily affecting the skin, eyes, and cardiovascular system. It is characterized by progressive calcification and degeneration of the elastic fibers throughout the body [1]. Rigal [2] first described the cutaneous lesions of PXE in 1881 and thought the disorder was akin to the xanthomatoses. In 1896, Darier [3] showed the typical histological changes in elastic fibers, thus proving that PXE was a separate condition. Grönblad and Strandberg subsequently recognized the association between ophthalmological and dermatological features in PXE [4].

The prevalence of this disease is estimated at 1 in 100,000 [5, 6] with an almost 2:1 female preponderance [7]. The genetic defect has been mapped to the ABCC6 gene on chromosome 16p13.1 [5, 7, 8]. Autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive patterns of inheritance have been described, but recent molecular genetic studies show only evidence for a recessive inheritance pattern [5].

The authors report one case of this rare disorder.

Clinical synopsis

A 55-year-old single man with progressive loss of vision was referred for the evaluation of his skin lesions.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

He had asymptomatic, small and multiple, yellow papules, coalescing into plaques, on the sides and front of his neck (Fig. 1), axillae, and periumbilical regions. He also had redundant skin folds on the axillae (Fig. 2). The lesions had been present since puberty and had been non-progressive for several years. He was hypertensive that was controlled by oral therapy. His cousin had similar skin lesions of long duration.

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

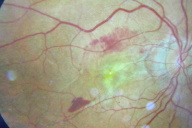

On examination, his peripheral pulses and blood pressure were normal. The skin in the involved areas was lax and redundant. Ophthalmoscopy revealed angioid streaks. Fluorescin angiography showed angioid streaks bilaterally and hemorrhages and neovascularization of the right eye (Fig. 3). With the above features, a clinical diagnosis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum was made.

Laboratory findings included normal serum calcium and phosphate levels: 9.5 mg/dl (8.5-10.6 mg/dl) and 4.1 mg/dl (2.5-4.5 mg/dl), respectively.

|  |

| Figure 4 | Figure 5 |

|---|

|

| Figure 6 |

|---|

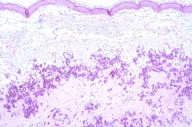

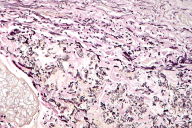

A skin biopsy was made from a papular lesion on the neck. The biopsy showed numerous, short, wavy, fibrillar to slightly granular material with eosinophilic appearance present between normal pink bundles of collagen (Fig. 4). Elastic tissue stain (Weigert) and stains for calcium deposits (Von Kossa) of the histopathological sections revealed short, broken, and frayed elastic fibers, with small, black, granular microdeposits of calcium along these fibers (Figs. 5 & 6). The features were consistent with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. The patient was then sent to undergo a thorough cardiovascular evaluation.

Discussion

The skin manifestations are the most prevalent characteristic of PXE and they are generally the first physical signs of the developing disorder [8]. The characteristic cutaneous findings are small, yellowish papules coalescing into plaques, which present classically along the sides of the neck, giving rise to a "gooseflesh" or "plucked chicken skin" appearance. Other sites of predilection are the axillae, periumbilical area, groin, perineum, and thigh [7, 8, 9]. These skin lesions are usually noted in the second or third decade [10]. In older individuals the involved skin is lax and hangs in large folds [6].

Although not pathognomonic of PXE [5], the characteristic eye signs are angioid streaks, which result from the rupture of elastic laminae in the Bruch membrane of the retina. They are irregular, reddish-brown, or grey lines that radiate from the optic disc. The typical age of onset is between 15 and 25 years and they appear to be present in at least 85 percent of patients with PXE [7, 9]. Although the angioid streaks are asymptomatic at first, they become the sites of choroidal neovascularization and subretinal hemorrhages later in life; central vision loss may occur in the case of macular involvement [10].

Generalized involvement of all large and medium sized arteries occurs. Eventually, manifestations of cardiovascular diseases develop and they result from the slow and progressive calcification of the elastic arterial walls. Reduction of vessel lumen causes ischemia; the excessive fragility of the vessel wall is responsible for hemorrhages [10]. Clinically, intermittent claudication is often the first sign of accelerated atherosclerosis and is the most common cardiovascular symptom, occurring in 30 percent of patients. Coronary artery disease and renovascular hypertension may occur at a much younger age in PXE patients and can result in angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, congestive cardiac failure, renal failure, or stroke [6, 7].

The diagnosis of PXE is based on physical findings and histological examination of the biopsy of the affected skin. Histologically, fragmented calcified elastic fibers are seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis, by use of elastic stains (e.g., Verhoeff-van Gieson, Orcein, or Weigert) and stains for calcium deposits (e.g., von Kossa) [7]. To facilitate and unify the clinical diagnosis of PXE, three major diagnostic criteria (characteristic skin involvement, characteristic histopathological features of lesional skin, and characteristic ocular disease) and two minor criteria (characteristic dermatopathological features in nonlesional skin and family history of PXE in first degree relatives) were defined at the Consensus Conference of 1992 [10].

The exact mechanism and cause of the calcifications are unknown. Damaged tissue, through a change in the local microenvironment, is known to be susceptible to calcium deposition in patients with an abnormal phosphorus-calcium product [6]. Recently, oxidative stress has been reported to play an important role in the pathogenesis of PXE [11].

Patients with PXE typically may have a normal life span, but morbidity and mortality depend on the extent of the systemic involvement [7]. The affected subjects have an increased propensity for ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular accidents, visual impairment, and cosmetic deterioration of the skin. Life expectancy is reduced if compared with the general population [9].

It is important to recognize the disease early, so that the risk of systemic complications can be minimized [7]. A prophylactic lifestyle, regular medical monitoring, and genetic counseling are highly recommended [10].

A routine annual review of the cardiovascular and ophthalmological status of affected persons is imperative in order to treat early hypertension and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as hypercholesterolemia, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and physical inactivity. This routine annual review is still imperative to avoid the sequelae of angioid streaks that extend into the macula of the eye [9].

There is no standard treatment for PXE. If the appearance of the skin lesion becomes a cosmetic problem, plastic surgical excision has been used successfully [7]. Laser photocoagulation can prevent retinal hemorrhages and neovascularization [9]. To reduce the risk of bleeding, platelet inhibitors such as aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as well as warfarin should generally be avoided [7].

Idiopathic hyperphosphatemia has been associated with PXE [12, 13]. Excessive dietary intake of calcium should be avoided in childhood and adolescence. The reason for this is that a correlation between the severity of PXE and high calcium intake has been suggested [14]. Regression of an acquired form of the disease (periumbilical perforating PXE) occurred with hemodialysis that corrected metabolic imbalances secondary to end-stage renal disease [15]. Moreover, there is in the literature a report on a clinical, histopathological, and electron-microscopic regression of PXE after the imposition of a low-calcium diet [16]. In a small study of six patients treated with aluminum hydroxide, three patients showed a significant clinical improvement of their skin lesions. The three patients also showed a histopathological regression of the disease in their target lesions [6]. There is one case report of PXE treated successfully with tocopherol acetate and ascorbic acid [11]. Finally, in a case of dystrophic calcinosis cutis related to PXE, the use of oral phosphate binders was shown to be encouraging as a possible treatment option [17]. Hence, further studies supporting these results could reveal the first real treatment options for PXE.

References

1. Bercovitch L, Terry P. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum 2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Jul;51(1 Suppl):S13-4. [PubMed]2. Rigal D. Observations pour server á l'histoire de la cheloide diffuse xantholasmique. Ann dermatol Syph. 1881;2:491-5

3. Darier J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Monatsschr Prakt Dermatol. 1896;23:609-14.

4. McKussick VA. Heritable disorders of connective tissue. 4th ed. St Louis: CV Mosby. 1973:475-520.

5. Brown SJ, Talks SJ, Needham SJ, Taylor AE. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: biopsy of clinically normal skin in the investigation of patients with angioid streaks. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Oct;157(4):748-51. [PubMed]

6. Sherer DW, Singer G, Uribarri J, Phelps RG, Sapadin AN, Freund KB, Yanuzzi L, Fuchs W, Lebwohl M. Oral phosphate binders in the treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Oct;53(4):610-5. [PubMed]

7. Laube S, Moss C. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Dis Child. 2005 Jul;90(7):754-6. [PubMed]

8. Le Saux O, Beck K, Sachsinger C, Silvestri C, Treiber C, Göring HH, Johnson EW, De Paepe A, Pope FM, Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Bercovitch L, Marais AS, Viljoen DL, Terry SF, Boyd CD. A spectrum of ABCC6 mutations is responsible for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Am J Hum Genet. 2001 Oct;69(4):749-64. [PubMed]

9. Viljoen D. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Grönblad-Strandberg syndrome). J Genet Med. 1988;25:488-490.

10. Christen-Zäch S, Huber M, Struk B, Lindpaintner K, Munier F, Panizzon RG, Hohl D. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: evaluation of diagnostic criteria based on molecular data. Br J Dermatol. 2006 Jul;55(1):89-93.

11. Takata T, Ikeda M, Kodama H, Kitagawa N. Treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum with tocopherol acetate and ascorbic acid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007 Jul-Aug;24(4):424-5. [PubMed]

12. Mallette LE, Mechanick JI. Heritable syndrome of pseudoxanthoma elasticum with abnormal phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism. Am J Med. 1987 Dec;83(6):1157-62. [PubMed]

13. McPhaul JJJr, Engel FL. Heterotopic calcification, hyperphosphatemia and angioid streaks of the retina. Am J Med. 1961 Sep;31:488-92. [PubMed]

14. Renie WA, Pyeritz RE, Combs J, Fine SL. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: high calcium intake in early life correlates with severity. Am J Med Genet. 1984 Oct;19(2):235-44. [PubMed]

15. Sapadin AN, Lebwohl MG, Teich SA, Phelps RG, DiCostanzo D, Cohen SR. Periumbilical pseudoxanthoma elasticum associated with chronic renal failure and angioid streaks--apparent regression with hemodialysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Aug;39(2 Pt 2):338-44. [PubMed]

16. Martinez-Hernandez A, Huffer WE, Neldner K, Gordon S, Reeve EB. Resolution and repair of elastic tissue calcification in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1978 Jun;102(6):303-5. [PubMed]

17. Federico A, Weinel S, Fabre V, Callen JP. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Apr;58(4):707-10. [PubMed]

© 2009 Dermatology Online Journal