Glomangioma

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D36nd715jwMain Content

Glomangioma

Marie Leger MD PhD, Utpal Patel MD PhD, Rajni Mandal MD, Ruth Walters MD, Kathleen Cook, Adele Haimovic, Andrew G Franks Jr

MD

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (11): 11

Department of Dermatology, New York University, New York, New YorkAbstract

A 22-year-old man presented with a 9-year history of multiple blue nodules on the medial aspect of his right arm. A biopsy specimen showed a cystic space with a cuboidal cellular lining that stained positive for α-smooth-muscle actin; these findings were consistent with multiple glomangiomas. We review the clinical and histopathologic characteristics of this rare entity.

History

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

A 22-year-old man presented to the Dermatology Clinic at Bellevue Hospital Center for evaluation of multiple blue nodules on the medial aspect of his right arm; the nodules had been present since he was 13 years old. The lesions had not increased in size or in number, but he did note that they were occasionally painful. No one in the family had similar lesions. He was otherwise healthy except for migraine headaches for which he took topiramate.

Physical examination

On the medial aspect of the right proximal arm, there were multiple, mobile, blue-hued dermal nodules that were approximately 3 mm in diameter. There also were multiple, non-scaly, erythematous pinpoint papules that surrounded the nodules.

Laboratory data

None

Histopathology

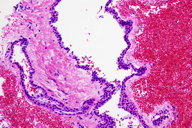

In the deep reticular dermis, there are dilated vascular spaces that are lined by cuboidal cells with round nuclei and eosinophilc cytoplasm.

Comment

Tumors comprised of glomus cells have been categorized into subtypes, which include solitary, multiple, solid, diffuse, adult, and pediatric. More recently, these tumors have been divided into two major subtypes: the glomus tumor and the glomangioma [1]. Glomangiomas differ clinically from glomus tumors in that they occur in childhood and adolescence, are usually asymptomatic, do not have a predilection for the subungal region, and often are multifocal [2, 3]. They can vary in color from pink-to-blue and often become darker with age; they may be plaque-like or nodular [4]. Multiple glomangiomas are rare and comprise about 10 percent of all glomus tumors [5]. Because glomangiomas are not neoplastic and resemble venous malformations, it has been suggested that they should more precisely be called glomuvenous malformations [6].

It is thought that glomus tumors and glomangiomas have different etiologies. Whereas glomus tumors are derived from the glomus body, which is responsible for thermoregulation, glomangiomas more closely resemble venous malformations [1, 6]. Although glomangiomas often manifest sporadic tumors, autosomal-dominant inheritance patterns with incomplete penetrance also have been described [7, 8]. A retrospective study of patients with superficial venous anomalies found that 63.8 percent of the glomangiomas were inherited [9]. Familial glomangiomas have been mapped to chromosome 1p21-p22 and are thought to a result of loss of function mutations in the cytoplasmic protein glomulin [6, 10].

Histopathologic features of glomangiomas contain more dilated venous channels than do glomus tumors and resemble venous malformations. Unlike venous malformations, they demonstrate single-to-multiple rows of surrounding cuboidal glomus cells. These cells stain positively for vimentin and α-smooth-muscle actin but are negative for desmin, von Willibrand factor, and S-100. Glomangiomas are less likely to have a capsule than glomus tumors [1, 2, 6].

Multiple glomangiomas can prove to be a diagnostic challenge. In a retrospective review of patients with multiple glomus tumors observed at the Mayo Clinic over 25 years, the mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 14.6 years (range three months to 44 years); referring physicians made the diagnosis in 18.2 percent of cases [7]. The differential diagnosis of multiple glomangiomas includes the blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) and vascular malformations. It has been suggested that many glomangiomas have been incorrectly diagnosed in the literature as BRBNS [2, 11]. Unlike BRBNS, glomangiomas are less compressible and there have not been reports of gastrointestinal involvement with multiple glomangiomas. Dilated venous spaces can be observed on histopathologic examination with both diseases; however, BRBNS lacks the characteristic glomus cells [11, 12]. Clinical criteria differentiating glomangiomas from vascular malformations include, in the former, a more raised, cobblestone-like appearance, the inability to be emptied by compression, the absence of phleboliths, pain on compression, and no pain with hormonal changes (menstruation, pregnancy, and puberty) [4, 9]. The occurrence of malignant glomus tumors is exceedingly rare [13].

A variety of treatment modalities have been employed for multiple glomangiomas, which include surgical excision, sclerotherapy, electron-beam radiation, argon and CO2 lasers, and periodic observation of asymptomatic lesions [14, 15, 16]. Differentiating glomangiomas from vascular malformations is important because each responds to different kinds of therapies. In contrast to venous malformations, compression of glomangiomas can cause pain, and as a recent series of patients with large facial glomangiomas suggests, they are less responsive to sclerotherapy [4].

References

1. Bolognia J, et al. eds. Dermatology, 2nd edition, London: Mosby, 2008: 114:17902. McEvoy BF, et al. Multiple hamartomatous glomus tumors of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1971; 104: 188 [PubMed]

3. Moor EV, et al. Multiple glomus tumors: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg 1999; 43: 436 [PubMed]

4. Mounayer C, et al. Facial ‘glomangiomas’: large facial venous malformations with glomus cells. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001; 45: 239 [PubMed]

5. Goodman TE, Abele DC. Multiple glomus tumors. Arch Dermatol 1971; 103: 11 [PubMed]

6. Brouillard P, et al. Mutations in a novel factor, glomulin, are responsible for glomuvenous malformations (“glomangiomas”). Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70: 866 [PubMed]

7. Anakwenze OA, et al. Clinical features of multiple glomus tumors. Derm Surg 2008; 34: 884 [PubMed]

8. Conant MA, Weisenfeld SL. Multiple glomus tumors of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1971; 103: 481 [PubMed]

9. Boon LM, et al. Glomuvenous malformation (glomangioma) and venous malformation. Arch Dermatol 2004 140: 971-976. [PubMed]

10. Boon LM et al. A gene for inherited cutaneous venous anomalies (“glomangiomas”) localizes to chromosome 1p21-22. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65:125 [PubMed]

11. Lu R, et al. Multiple glomaniomas: potential for confusion with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 52: 731 [UI:]

12. Schopff JG, et al. Glomangioma: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2009; 23: 24 [PubMed]

13. Hayashi M, et al. Malignant glomus tumors arising among multiple glomus tumors. J Orthop Sci 2008; 13: 472 [PubMed]

14. Barnes L, Estes SA. Laser treatment of hereditary multiple glomus tumors. J Derm Surg Oncol 1986; 12: 912 [PubMed]

15. D’Acri AM, et al. Multiple glomus tumors: recognition and diagnosis. Skinmed 2002; Nov-Dec: 94 [PubMed]

16. Parsons ME, et al. Multiple glomus tumors. Int J Dermatol 1997; 36: 894. [PubMed]

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal