Composite cutaneous atypical vascular lesion and Langerhans cell histiocytosis after radiation for breast carcinoma: Can radiation induce langerhans cell histiocytosis?

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D36bc0t5k9Main Content

Composite cutaneous atypical vascular lesion and Langerhans cell histiocytosis after radiation for breast carcinoma: Can radiation

induce Langerhans cell histiocytosis?

Zenggang Pan MD PhD1, Kirby I Bland MD2, Shi Wei MD PhD1

Dermatology Online Journal 17 (12): 6

1. Department of Pathology2. Department of Surgery

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama

Abstract

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) refer to small vascular proliferations in radiated skin that may progress to angiosarcoma and typically develop after breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. We present a case of composite AVL and Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) in a 57-year-old woman who received surgery and radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma of the breast. The patient developed AVLs 4 years after radiation. Biopsies of multiple erythematous nodules at the same site one year later revealed intermixed AVL and LCH, some of which coexisted within the same lesion. To our knowledge, LCH has not been recorded at the site of radiation in the English language literature. Our case not only highlights the importance of close cutaneous surveillance and a low threshold for biopsy in patients with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy, but also raises the possibility of radiation as the inducement of cutaneous LCH.

Introduction

Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesion (AVL) and angiosarcoma have been well-documented in patients with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy for breast carcinoma [1, 2, 3, 4]. The clinical behavior and morphologic features of radiation-associated angiosarcoma are comparable to sporadic mammary angiosarcoma, whereas AVL typically presents as one or multiple small, flesh-colored papules or erythematous patches that arise in the dermis at the site of radiation; they resemble lymphangioma and/or lymphangioendothelioma microscopically. Whereas most AVLs follow a benign course, they may rarely progress to angiosarcoma, usually after multiple recurrences. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a group of idiopathic disorders of unknown pathogenesis, owing to the ongoing debate over whether LCH is a reactive or neoplastic process. Langerhans cell histiocytosis has not been documented at the site of radiation. Herein we describe a case of composite AVL and LCH that developed after radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. Our case suggests a possible pathogenesis of cutaneous LCH.

Case report

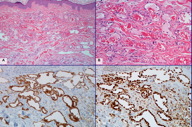

A 57-year-old woman was diagnosed with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the right breast in 2005. The patient underwent breast-conserving surgery and sentinel lymph node biopsy followed by radiation therapy. One year later, she was noted to have a skin lesion of the right breast in the area of radiation and a biopsy revealed perivascular acute and chronic inflammation consistent with radiation dermatitis. In January, 2009, the patient noticed a few small lumps in the same area on the right breast. Punch biopsies of these lesions demonstrated proliferation of anastomosing, thin-walled vessels in the superficial and deep dermis (Figures 1A and 1B). These vessels were lined by a single layer of “hobnail” endothelial cells with occasional nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia with no prominent nucleoli. The lining cells were strongly immunoreactive with antibodies directed against CD31 and FLI-1 (Figures 1C and 1D). A diagnosis of radiation-associated AVL was rendered.

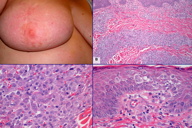

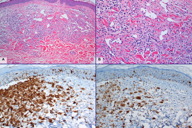

The patient was followed up closely without further treatment. In January, 2010, multiple erythematous nodules developed in her right breast, extending out from the surgical scar (Figure 2A). In addition, there were scattered small erythematous papules on her right axilla, anterior mid chest wall, left breast, and right groin. Biopsies of several skin nodules from the right breast revealed AVLs similar to the previous biopsy, but showed focal aggregates of slightly more atypical endothelial cells, raising the possibility of tumor progression. Interestingly, the biopsies from other similar skin nodules displayed a separate, cellular proliferation of monomorphic neoplastic cells in the dermis (Figure 2B). The cells of interest exhibited abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and oval, elongated or folded nuclei with occasional nuclear grooves (Figure 2C). Thus, the histological features are those characteristic of LCH. The lesional cells extensively infiltrated into the superficial and deep dermis, with focal pagetoid spread to the overlying epidermis (Figure 2D). The lesions of LCH were predominantly located at the site of previous radiation, some of which were intermixed with AVLs (Figures 3A and 3B). In addition, biopsies from the isolated erythematous papules on the anterior chest wall and the left breast revealed purely LCH without AVL. The diagnosis of LCH was further confirmed by the immunoexpression of CD1a and S-100 protein by tumor cells (Figures 3C and 3D).

Further physical examination of this patient did not show any notable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary lymphadenopathy. Imaging analyses with computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography revealed no evidence of metastasis to any distal organs. A mammogram of the right breast was unremarkable except for focal fibrosis in the previous surgical site.

Discussion

In this report, we describe a very interesting case of cutaneous composite AVL and LCH arising at the site of previous surgery and radiation therapy for breast carcinoma. AVL typically develops as one or more, small, colorless to slightly erythematous papules within a period of 3-6 years after radiotherapy [2, 3]. Microscopically, AVL embraces a spectrum of changes ranging from benign, angiomatous proliferations of vessels to those with significant atypia, the latter representing a “premalignant” lesion or “incipient angiosarcoma.” Compared with radiation-associated angiosarcoma, AVL has a shorter interval time following radiation (average 3.5 years vs. 6 years), and is smaller (median 0.5 cm vs. 7.5 cm) and fairly well circumscribed [2, 3]. AVL is usually confined within the superficial to mid dermis and is composed of complex anastomosing and focally dilated vascular spaces. However, separation of AVL from well-differentiated angiosarcoma may be difficult because of significant overlapping of these two entities clinically and histologically. Therefore, postradiation AVL and well-differentiated angiosarcoma may represent a morphologic continuum rather than two separate and histologically distinct entities. In our case, the initial cutaneous vascular lesions developed 4 years after radiation, an interval typical of AVL, whereas the subsequent biopsies demonstrated greater architectural and cytological atypia, thus suspicious for tumor progression. Therefore, the patient may require a closer follow-up and more aggressive clinical management.

LCH is less common in adults than in children and it mostly involves the bone, lung and skin [5, 6, 7]. Morphologically, cells of LCH typically have abundant clear to pink cytoplasm and indented nuclei with a concomitant infiltration of lymphocytes and eosinophils. The lesional cells characteristically express CD1a and S-100 protein. The clinical course of LCH is often unpredictable, varying from spontaneous regression and resolution to repeated recurrence, rapid progression, and death. LCH localized to one organ, usually the bone, skin, or lymph node, is associated with a favorable prognosis, which may need minimal or even no treatment [5, 6, 8]. The pathogenesis of LCH is not well understood. Pulmonary LCH has a strong association with smoking [9]. Nonetheless, an ongoing debate still exists over whether this is a reactive or a neoplastic process. The patient in our case developed cutaneous LCH at the site of radiation 5 years after treatment. The lesions of intermixed LCH and AVL predominantly surrounded the site of radiation and presented as erythematous nodules, whereas LCH lesions on the anterior chest wall and the left breast presented as several small red papules, suggesting satellite spreading. Systemic investigations revealed no extra-cutaneous involvement. Therefore, this composite LCH and AVL represented a primary cutaneous event. Moreover, the cutaneous LCH in this case exhibited extensive dermal infiltrate in sheets and focal pagetoid epidermal spread without associated classic eosinophilia, thus it may be mistaken for a recurrent breast carcinoma or melanoma.

The composite cutaneous lesions in our patient are of substantial interest. The clear association of radiation and cutaneous AVL raises the possibility of radiation as the inducement of the LCH as well. Previous studies have suggested that, in addition to epidermal Langerhans cells, other potential cellular origins in the dermis may be induced by local environmental stimuli to acquire a Langerhans cell phenotype [10, 11]. To our knowledge, radiation-associated LCH has never been described in the English literature. One report described an isolated cutaneous LCH 15 months after surgery and radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. However, the lesion occurred below the breast, making it more likely to be an incidental finding [12]. The significance of radiation in development of cutaneous LCH remains to be determined.

References

1. Abbott R, Palmieri C. Angiosarcoma of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2008;5:727-736. [PubMed]2. Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: Clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:983-996. [PubMed]

3. Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: A clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:943-950. [PubMed]

4. Scow JS, Reynolds CA, Degnim AC, Petersen IA, Jakub JW, Boughey JC. Primary and secondary angiosarcoma of the breast: The mayo clinic experience. J Surg Oncol 2010;101:401-407. [PubMed]

5. Arico M, Girschikofsky M, Genereau T, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the international registry of the histiocyte society. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:2341-2348. [PubMed]

6. Stockschlaeder M, Sucker C. Adult langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Haematol 2006;76:363-368. [PubMed]

7. Arico M. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: More questions than answers? Eur J Cancer 2004;40:1467-1473. [PubMed]

8. Singh A, Prieto VG, Czelusta A, McClain KL, Duvic M. Adult langerhans cell histiocytosis limited to the skin. Dermatology 2003;207:157-161. [PubMed]

9. Travis WD, Borok Z, Roum JH, et al. Pulmonary langerhans cell granulomatosis (histiocytosis X). A clinicopathologic study of 48 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:971-986. [PubMed]

10. Merad M, Ginhoux F, Collin M. Origin, homeostasis and function of Langerhans cells and other langerin-expressing dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8(12):935-947. [PubMed]

11. Egeler RM, van Halteren AG, Hogendoorn PC, Laman JD, Leenen PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: fascinating dynamics of the dendritic cell-macrophage lineage. Immunol Rev 2010;234(1):213-232. [PubMed]

12. O'Kane D, Jenkinson H, Carson J. Langerhans cell histiocytosis associated with breast carcinoma successfully treated with topical imiquimod. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34:e829-832. [PubMed]

© 2011 Dermatology Online Journal