Disseminated fusariosis presenting as panniculitis-like lesions on the legs of a neutropenic girl with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D366w63943Main Content

Disseminated fusariosis presenting as panniculitis-like lesions on the legs of a neutropenic girl with acute lymphoblastic

leukemia

Cathryn Z Zhang1, Maxwell A Fung MD2, Daniel B Eisen MD2

Dermatology Online Journal 15 (10): 5

1. Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio2. University of California, Davis, Department of Dermatology, Sacramento, California. dbeisen@ucdavis.edu

Abstract

Fusarium is a filamentous fungus found naturally in the soil and as a contaminant of plumbing systems. In immunocompetent patients, Fusarium causes localized infection, most commonly onychomycosis. Fusarium tends to be resistant to commonly used antifungal medications. In immunocompromised patients, this antifungal resistance is of particular concern because localized infection quickly becomes disseminated disease with high mortality rates. Disseminated fusariosis presents with skin lesions more often than any other systemic fungal infection. We present a case of fusariosis in an 11-year-old neutropenic patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia whose only symptom of the fungal infection consisted of painful, indurated nodules and plaques on her legs. The diagnosis and treatment of this invasive fungal infection is also discussed.

Introduction

With more intensive chemotherapeutic regimens being used in practice, neutropenia is becoming a more common problem. Depending on the chemotherapy regimen, the incidence of Grade III/IV neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count less than 1000 per microliter) can be as high as 100 percent [1]. Neutrophils are among the first line defense against microbial infections. They kill pathogens intracellularly via phagocytosis or extracellularly via the release of cytotoxic granules [2, 3]. Given the role of neutrophils in innate immunity, it is not surprising that neutropenia would increase infection risk. The relation between leukocyte count and infection risk has been recognized for decades and was first described in depth by the landmark Bodey paper in 1966 [4]. Even for neutropenia lasting 1 week or less, the serious infection rate ranged from 10-28 percent depending on severity of neutropenia [5]. Often times, the earliest signs of an infection are cutaneous lesions. Conversely, the skin may be the portal of entry for microbes, which can later spread to cause disseminated disease.

Some infections are uniquely associated with neutropenia. Bacterial infections of note include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus viridans, and Clostridium species. Fungal infections that are common in neutropenic patients include Candida species, Aspergillus, and Fusarium [6, 7, 8]. Based on the clinical appearance alone, it is nearly impossible to identify the pathogenic cause. Each pathogen may have a characteristic skin lesion, but most tend to have a wide range of possible presentations. For instance, the classic cutaneous lesion seen in pseudomonal infections is ecthyma gangrenosum, but almost identical ecthyma gangrenosum-like lesions can be seen in Aspergillus or Fusarium infections. In addition, lesions will often evolve as the infection progresses.

Case presentation

Our hospital consult team was called to see an 11-year-old girl with complaints of erythematous painful nodules and plaques on her lower extremities (Fig. 1). Her medical history was significant for acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosed 1 month prior. These lesions appeared on day 22 of the patient's induction chemotherapy regimen, which consisted of cytarabine, vincristine, daunorubicin, prednisone, methotrexate, and pegylated asparaginase. At the time of evaluation, the nodules had been enlarging for 2 days despite intravenous antibiotics that were started by the primary team.

On exam, the patient was afebrile. She had mild edema around her right eye with mild ptosis. On skin exam, she had several 1-3 cm in diameter erythematous indurated nodules and plaques on the posterior aspect of her right and left thighs and distal left leg. The lesions were painful to palpation. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

The most recent laboratory studies at the time of consult showed a white blood cell count of 0.6 x 109 cells per liter, with an absolute neutrophil count of 56 cells per microliter, hemoglobin of 9.7 grams per deciliter, and platelet count of 53,000.

The differential diagnosis for the erythematous indurated nodules found in our neutropenic patient included infectious etiology, erythema nodosum, and Sweet syndrome. Primary skin infection or cutaneous manifestation of a disseminated infection was high on the differential. The appearance of the lesions resembled panniculitis, which made erythema nodosum a possibility. Sweet syndrome does not classically present with erythematous nodules. However, a subtype termed subcutaneous Sweet syndrome has been described in which lesions resemble erythema nodosum and appear most frequently on the lower extremities [9]. A punch biopsy of the largest lesion was taken and submitted for both histopathology and culture.

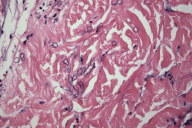

Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen revealed numerous large septate branching hyphae infiltrating the reticular dermis, which is consistent with Aspergillus, Fusarium, or Pseudallescheria (Fig. 2) [10]. Identification of Fusarium species in the fungal culture from the same biopsy specimen clinched the diagnosis of fusariosis in this case. Blood cultures for fungus showed no growth after 1 month.

Following the diagnosis of cutaneous Fusarium infection, the patient was started on a regimen of voriconazole 200 mg by mouth twice daily and liposomal amphotericin B, 7.5 kg/day intravenously. The amphotericin was discontinued after 6 weeks due to intense pruritus resulting from the infusions and improvement in the patient's clinical symptoms. After discontinuing the amphotericin she underwent an allogeneic bone marrow transplant while still on the voriconazole for a 12-week course. At time of publication, she was alive and well with no recurrence of her infection or leukemia.

Discussion

When evaluating a neutropenic patient presenting with new skin lesions, infectious etiology should be high on the differential, given the high rates of infection in neutropenic patients [5]. Other non-infectious causes should be considered based on the clinical picture. When there is not a clear explanation for the new skin lesions, biopsy should be performed and sent in for both tissue culture and histopathologic examination.

Fusarium species are filamentous fungi found in the soil. They also survive in water by the formation of biofilms [3]. They can be transmitted to patients via contaminated hospital plumbing systems [11]. In immunocompetent people, Fusarium infection most commonly presents as onychomycosis, keratitis in contact lens wearers, and localized skin infection at the site of trauma [3]. In immunocompromised patients, localized infection will often progress to disseminated fusariosis because of the host's impaired defense against fungi. Neutrophils are a critical line of defense against fungal infections because hyphae are destroyed extracellularly by oxidative cytotoxic mechanisms of neutrophils [2]. The mortality rate in disseminated fusariosis has been reported to be in the range of 67 percent to 79 percent in recent studies [12, 13]. Skin involvement is seen in 70 percent of patients with fusariosis, more than any other fungal pathogen [14]. The most characteristic skin lesion is an erythematous or gray papule or nodule that becomes centrally purpuric and then develops a thick eschar [6, 8]. In 50 percent of patients with fusariosis, skin lesions are the sole source of diagnostic material, highlighting the crucial role of dermatologists evaluating inpatient neutropenic patients presenting with new lesions [8].

The diagnosis of Fusarium infection is made by identification of fungi with septate hyphae and acute angle-branching on histopathology. This appearance is indistinguishable from the more common fungal pathogen, Aspergillus, as well as the relatively obscure fungus Pseudallescheria boydii [2]. Further characterization of the fungal pathogen can be made using culture of blood or tissue specimen. To differentiate these histologically and clinically identical fungal pathogens, newer molecular techniques have been explored, including in situ hybridization against ribosomal RNA sequences[10] and polymerase chain reaction [15, 16]. Both molecular techniques have shown promising results in small studies, but are more costly and not widely available. Proper identification of the fungal pathogen is important because Fusarium and Pseudallescheria tend to be much more resistant to antifungal therapy than Aspergillus [10].

There are no well-designed prospective studies looking at treatment of disseminated fusariosis, so definitive guidelines on treatment are not well established. The response of Fusarium infection to various antifungals can be gleaned from retrospective analyses or case series. The older triazoles (e.g., itraconazole and fluconazole) and echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin and micafungin) are ineffective against Fusarium [2]. Some success has been seen in using lipid formulations of amphotericin B and the newer triazoles (voriconazole and posaconazole). Amphotericin B has been reportedly effective in doses ranging from 7.5-15 mg/kg/day [17]. Voriconazole is typically begun with a 6 mg/kg loading dose given twice daily intravenously followed by a maintenance dose of 4 mg/kg [18]. An oral formulation is available for voriconazole and was used for our patient. Some clinicians will use a combination of antifungals when treating disseminated fusariosis [3, 19]. However, the evidence is limited to case reports so no particular combination can be deemed superior. The recommended duration of treatment is not clearly defined. Three months of treatment was the median in studies looking at voriconazole treatment of disseminated fungal infections [20, 21]. Barring intolerable adverse effects, at least 3 months of treatment is a reasonable goal, as was used in our patient. Resolution of neutropenia is the best predictor of survival, so colony stimulating factors might be a logical adjunctive treatment [13]. However, no survival benefit has been found in the use of granulocyte colony stimulating factor; these treatments should be only used in a case by case basis [3, 13, 22].

The current Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for prophylaxis in neutropenic patients recommends hospitalization with commencement of IV antibiotics in patients with febrile neutropenia. If the patient remains febrile after 5 days, then adding an antifungal should be considered. In afebrile neutropenic patients, routine prophylaxis with antibiotics against either bacterial or fungal organisms should be avoided. The sole exception is the use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients at risk for pneumocystis pneumonia [22]. Fungal prophylaxis decreases the rate of invasive fungal infection but shows no mortality benefit [23].

Summary

We present this case of fusariosis with atypical cutaneous findings in an afebrile patient to highlight the variable presentation of this invasive fungal infection and the importance of early diagnosis. This case also emphasizes the importance of tissue culture in helping establish the diagnosis. Blood cultures are not always positive in the setting of disseminated Fusarium infection, as was the situation with our patient. Clinicians taking care of neutropenic patients should have a high index of suspicion for opportunistic fungal infections given their ubiquitous presence in the environment. Prompt diagnosis and initiation of treatment is essential to maximize the chance of survival for any patient with this highly lethal opportunistic infection.

References

1. Dale, D.C., J. Crawford, and G. Lyman, Chemotherapy-Induced Neutropenia and Associated Complications in Randomized Clinical Trials: An Evidence-Based Review [abstract 1638]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol, 2001. 20(410a).2. Lionakis, M.S. and D.P. Kontoyiannis, Fusarium infections in critically ill patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2004. 25(2): p. 159-69. [PubMed]

3. Nucci, M. and E. Anaissie, Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2007. 20(4): p. 695-704. [PubMed]

4. Bodey, G.P., et al., Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med, 1966. 64(2): p. 328-40. [PubMed]

5. Crawford, J., D.C. Dale, and G.H. Lyman, Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer, 2004. 100(2): p. 228-37. [PubMed]

6. Bodey, G.P., Dermatologic manifestations of infections in neutropenic patients. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 1994. 8(3): p. 655-75. [PubMed]

7. Ellis, M., Febrile neutropenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2008. 1138: p. 329-50. [PubMed]

8. Mays, S.R. and P.R. Cohen, Emerging dermatologic issues in the oncology patient. Semin Cutan Med Surg, 2006. 25(4): p. 179-89. [PubMed]

9. Guhl, G. and A. Garcia-Diez, Subcutaneous sweet syndrome. Dermatol Clin, 2008. 26(4): p. 541-51, viii-ix. [PubMed]

10. Hayden, R.T., et al., In situ hybridization for the differentiation of Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Pseudallescheria species in tissue section. Diagn Mol Pathol, 2003. 12(1): p. 21-6. [PubMed]

11. Anaissie, E.J., et al., Fusariosis associated with pathogenic fusarium species colonization of a hospital water system: a new paradigm for the epidemiology of opportunistic mold infections. Clin Infect Dis, 2001. 33(11): p. 1871-8. [PubMed]

12. Boutati, E.I. and E.J. Anaissie, Fusarium, a significant emerging pathogen in patients with hematologic malignancy: ten years' experience at a cancer center and implications for management. Blood, 1997. 90(3): p. 999-1008. [PubMed]

13. Nucci, M., et al., Outcome predictors of 84 patients with hematologic malignancies and Fusarium infection. Cancer, 2003. 98(2): p. 315-9. [PubMed]

14. Bodey, G.P., et al., Skin lesions associated with Fusarium infection. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2002. 47(5): p. 659-66. [PubMed]

15. Healy, M., et al., Use of the Diversi Lab System for species and strain differentiation of Fusarium species isolates. J Clin Microbiol, 2005. 43(10): p. 5278-80. [PubMed]

16. Hue, F.X., et al., Specific detection of fusarium species in blood and tissues by a PCR technique. J Clin Microbiol, 1999. 37(8): p. 2434-8. [PubMed]

17. Walsh, T.J., et al., Safety, tolerance, and pharmacokinetics of high-dose liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) in patients infected with Aspergillus species and other filamentous fungi: maximum tolerated dose study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2001. 45(12): p. 3487-96. [PubMed]

18. Consigny, S., et al., Successsful voriconazole treatment of disseminated fusarium infection in an immunocompromised patient. Clin Infect Dis, 2003. 37(2): p. 311-3. [PubMed]

19. Ho, D.Y., et al., Treating disseminated fusariosis: amphotericin B, voriconazole or both? Mycoses, 2007. 50(3): p. 227-31. [PubMed]

20. Walsh, T.J., et al., Voriconazole in the treatment of aspergillosis, scedosporiosis and other invasive fungal infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2002. 21(3): p. 240-8. [PubMed]

21. Perfect, J.R., et al., Voriconazole treatment for less-common, emerging, or refractory fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis, 2003. 36(9): p. 1122-31. [PubMed]

22. Hughes, W.T., et al., 2002 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis, 2002. 34(6): p. 730-51. [PubMed]

23. Goldberg, E., et al., Empirical antifungal therapy for patients with neutropenia and persistent fever: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer, 2008. 44(15): p. 2192-203. [PubMed]

© 2009 Dermatology Online Journal