Pseudolymphoma evolving into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D35ks58934Main Content

Niroshana Anandasabapathy MD PhD, Melissa Pulitzer MD, Wendy Epstein MD, Karla Rosenman MD, Jo-Ann Latkowski MD

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (5): 22

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityAbstract

A 46-year-old man presented with a 1-year history of asymptomatic papules on the right arm, without an antecedent event. Initial clinical and histopathologic features were consistent with a pseudolymphoma without gene rearrangements, and the patient was treated with intralesional glucocorticoids. Four months later, the patient developed additional papules and plaques on the right arm. At this time, clinical and histopathologic features were most consistent with a T-cell-rich, large B-cell lymphoma, with monoclonal immunoglobulin light chain gene rearrangement. Systemic evaluation showed no evidence of extracutaneous involvement. The transformation of a pseudolymphoma into a large B-cell lymphoma is a rare event. This patient's subtype, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma-other, carries an intermediate prognosis when compared to the more aggressive subtype that generally appears on the legs of elderly women, and more indolent folliculocentric subtype. Potential therapeutic options include local radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and rituximab.

Clinical synopsis

A 46-year-old Caucasian man presented to the Dermatology Clinic at Bellevue Hospital Center in August, 2006, with a 1-year history of asymptomatic papules on the medial aspect of the right arm. The patient denied itch, pain, and preceding trauma or insect bite. A punch biopsy specimen showed a dense, dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages that suggested a reactive process. A second biopsy specimen failed to show monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy or light chains or T-cell-receptor gene rearrangements. A diagnosis of pseudolymphoma was made. The patient was treated with intralesional glucocorticoids with some improvement. Four months later, several plaques and nodules were noted proximal to the original papules on the right arm. Several punch biopsies were performed.

The patient's past medical history included arthritis, degenerative joint disease, and anxiety. He takes no medications.

Physical Examination

On the posterior aspect of the right upper arm, there were several fleshy papules and firm, subcutaneous nodules with overlying erythema and mild atrophy. On the medial aspect of the right forearm, there were several, slightly erythematous papules.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

A complete blood count and basic metabolic panel were normal. A human immunodeficiency test and Lyme titers were negative. Blood-flow cytometry examination showed normal T-and B-cell counts, and there was no evidence of a malignant lymphoproliferative disorder by cell-marker analysis. A positron emission tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis as well as a bone-marrow biopsy specimen showed no evidence of systemic involvement

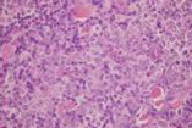

Histopathology

There is a nodular pan-dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, which includes large clusters of L26+ atypical B lymphocytes, with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Small peripheral CD3+ T lymphocytes show a normal CD4:CD8 ratio and preservation of CD5 and CD7.

Immunophenotyping analysis shows monoclonal immunoglobulin light chain gene rearrangements. No monoclonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangements are identified.

Comment

The term cutaneous pseudolymphoma describes a benign, reactive process that mimics lymphoma both clinically and histopathologically. Pseudolymphomas are comprised of a heterogenous mixture of benign reactive T-and B-cell lymphoproliferative patterns although a B-cell infiltrate is more common. While the incidence rate of cutaneous T-cell pseudolymphomas is not reported, cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphomas have have a male:female ratio of 2:1 and a white:black ratio of 10:1, with mean age of presentation of 34 years [1, 2].

Prior to the advent of immunohistochemical stains, these lesions were characterized histolopathologically and clinically. By definition, pseudolymphoma consisted of dense infiltrates of lymphocytes and the condition did not progress to systemic disease within five years after initial biopsy. No clear histopathologic criteria have been established to distinguish lymphomas from pseudolymphomas; however, diagnosis appears to be based predominantly on histopathologic findings. For example, in cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma, the B-cell infiltrate is nodular and tends to favor the papillary dermis. In contrast, the infiltrate in cutaneous B-cell lymphoma favors the dermis and may extend into the subcutaneous fat [3].

Immunophenotyping is used to characterize the infiltrate as T-cell or B-cell predominant. Immunogenotyping studies do not distinguish pseudolymphomas from lymphomas. T-cell receptor and B-cell immunoglobulin light or heavy chain gene rearrangements have been detected in both pseudolymphomas and lymphomas; cases of dual lineage rearrangements have been identified [4]. The presence of a clonal population in a pseudolymphoma does not predict evolution into a lymphoma [5].

Although pseudolymphoma is considered a reactive process, most cases are idiopathic. Other etiologies include drugs (anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, antihypertensives, and antidepressants), tattoos, insect bites, vaccinations, trauma, and infections (human immunodeficiency virus, varicella-zoster virus, and Lyme borreliosis). Higher rates of lymphoma have been observed and characterized in patients with associated chronic inflammatory states, immunodeficiency states, or chronic infections, which include Epstein-Barr virus, HTLV, Chlamydia, and H. pylori [6].

Although rare, reports of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma evolving into B-cell lymphoma have been described. In one study of 4 cases, transformation of 1 case of pseudolymphoma into a large B-cell lymphoma was identified, similar to our patient [7]. In this case, however, the lesion was present for 10 years prior to the diagnosis of pseudolymphoma. A period of 32 months elapsed between the initial diagnosis and transformation into a large cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL).

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) has traditionally been considered to be an aggressive lymphoma, which occurs on the legs of elderly women. The new WHO-EORTC (World Health Organization - European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer) classification of cutaneous lymphomas has recognized that this group of B-cell lymphomas is more heterogeneous [8]. This new classification has an additional category, DLBCL-other, which would include our patient. It is considered a lymphoma of intermediate clinical behavior. The male:female ratio in one large study (93 cases of cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma) for the DLBCL-other was 0.3:1, with median age of 72 years. Disease specific life expectancy was 50 percent at 5 years and 50 percent at 10 years [9].

Cutaneous DLBCL-other must be distinguished from its nodal counterpart, and thus a systemic evaluation is warranted. It should include a complete physical examination with palpation of lymph nodes, liver, and spleen; complete blood cell count with differential analysis; liver function tests; lactate dehydrogenase; and flow cytometry analysis of blood. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis as well as a bone-marrow biopsy are recommended.

No single optimal treatment for cutaneous B-cell lymphoma has been established. Local radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy with CHOP are more commonly used. In 1 recent report of 5 cases, rituximab was used in patients with appreciable co-morbidities or extensive disease and in those who had refused radiation therapy. Three patients remained in complete remission after 39 months: one died of unrelated causes after 5.5 years of remission and 1 patient had a single cutaneous nodule develop after 3 years that was treated with local radiotherapy [13].

References

1. Kerl H, Ackerman AB. Inflammatory diseases that simulate lymphomas: cutaneous pseudolymphomas. In: Fitzpatrick TB, et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993:13152. Caro WA, Helwig EB. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. Cancer 1969;24:487

3. Ploysangam T, et al. Cutaneous pseudolymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;38:896

4. Kazakov DV, et al. Primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders with dual lineage rearrangement. Am J Dermatopathol 2006; 28:399

5. Landa NG, et al. Lymphoma vs pseudolymphoma of the skin: gene rearrangement study of 21 cases with clinicopathological correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 29:945

6. Fisher SG, Fisher RI. The emerging concept of antigen-driven lymphomas: epidemiology and treatment implications. Curr Opin Oncol 2006;18:417

7. Brittain F, et al. Progression of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma to cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Cutan Med Surg 2002;6:519

8. Willemze R, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 2005; 105:3768

9. Kodoma A, et al. Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: clinicopathologic features, classification, and prognostic factors in a large series of patients. Blood 2005;106:2491

10. Lazaris AC, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the skin. Dermatol Online J 12(4):16

11. Willemze R. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: classification and treatment. Curr Opin Oncol 2006;18: 425

12. Hoefnagell JJ, et al. Expression of B-cell transcription factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol 2006;19:1270

13. Gitelson E, et al. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma responds to rituximab: a report of five cases and a review of the literature. Leuk Lymph 2006;47:1902

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal