Muir-Torre syndrome

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D34r39610vMain Content

Muir-Torre syndrome

Daniel Navi MD, Akhil Wadhera MD, Maxwell A Fung MD, Nasim Fazel MD DDS

Dermatology Online Journal 12 (5): 4

University of California Davis Department of Dermatology. nasim.fazel@ucdmc.ucdavis.eduAbstract

A 65-year-old man with a history of multiple neoplastic and pre-neoplastic gastrointestinal lesions as well as urogenital carcinoma presented for evaluation of two asymptomatic skin-colored papules in the head and neck region. Biopsy revealed sebaceous neoplasms and immunohistochemical staining was negative for the presence of hMSH-2 protein in both specimens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Muir-Torre syndrome in the setting of a prior history of visceral malignancies. Muir-Torre Syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis associated with mutations in mismatch repair proteins, hMSH-2 and hMLH-1, which predispose affected patients to visceral malignancies as well as sebaceous gland neoplasms.

Clinical synopsis

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of two pink papules located on the nose and neck. The lesions were asymptomatic and had been present for several months. Past medical history was significant for essential hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The patient also had a prior history of multiple gastrointestinal tumors including small bowel adenocarcinoma (status-post left colonic resection at age 58), dysplastic cecal polyp (status-post right hemicolectomy at age 63), colonic tubular adenoma (status-post colonoscopic resection at age 64), and a history of prostate adenocarcinoma. He denied any systemic symptoms including fever, chills, weight loss, change in appetite, or fatigue. Family history was significant for multiple first-degree relatives with established diagnoses of gastrointestinal and genitourinary malignancies.

Physical examination revealed a skin-colored keratotic papule on the nose and a verrucous nodule on the neck. The biopsy diagnosis of both lesions was sebaceous adenoma. Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of hMLH-1 mismatch repair (MMR) protein but absent expression of hMSH-2 protein in both specimens. These findings established a diagnosis of Muir-Torre syndrome. The patient has presented with over 10 cutaneous lesions involving the upper extremities and trunk since the time of presentation. Biopsy of these lesions revealed sebaceous neoplasms including sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and SCC with sebaceous differentiation. Surveillance for additional internal malignancies has thus far been negative.

|  |

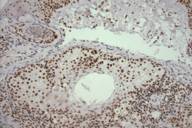

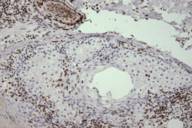

| Figure 1A | Figure 1B |

|---|

|  |

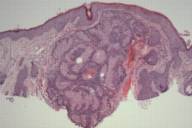

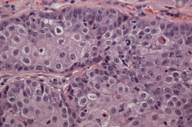

| Figure 2A | Figure 2B |

|---|---|

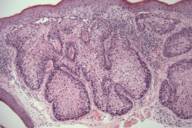

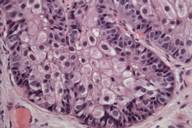

| Figure 2. Sebaceous adenoma on the cheek. | |

| A) Nodular tumor aggregates in the upper dermis. (H&E, 40×) B) Vacuolated cytoplasm of well-differentiated sebocytes. (H&E, 400×) | |

Comment

Muir-Torre Syndrome (MTS) is a rare genodermatosis most often diagnosed by the synchronous or metachronous occurrence of at least one sebaceous gland neoplasm and at least one internal malignancy. Less often, a clinical diagnosis of MTS can be made in patients with multiple keratoacanthomas and a visceral malignancy on the basis of a positive family history [1]. The syndrome is characterized by an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with variable penetrance and expression, although sporadic cases may also occur. The median age of onset is 55 years with a male to female ratio of 3:2. Because MTS-associated sebaceous gland neoplasms comprised of sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous epitheliomas, and sebaceous carcinomas are quite rare as sporadic tumors, their diagnosis must raise the suspicion and subsequent work-up for underlying MTS. The visceral malignancies found in MTS originate in the gastrointestinal tract in 61 percent of cases with colorectal carcinoma. Malignancy of the urogenital system is the second most common, accounting for 22 percent of cases [2 ,3]. Colon carcinoma associated with MTS occurs proximal to the splenic flexure in the majority of patients. In contrast, the majority of individuals without MTS who develop colorectal cancer have distal lesions [3]. Another characteristic feature of MTS-associated visceral malignancies is that they are less aggressive than their sporadic counterparts. As a result, most patients have good long-term survival even in the setting of metastatic disease [1, 3].

The cutaneous neoplasms of this syndrome also have some noteworthy features. The sebaceous tumors often display unusual histopathologic features such as cystic structures, solid basaloid sheets, mucinous areas, and convoluted glands [4, 5]. Two cutaneous lesions are believed to be the most sensitive markers for MTS: sebaceous adenoma and sebaceous epithelioma. The latter tumor is also referred to as basal cell carcinoma with sebaceous differentiation or a sebaceoma. Sebaceous adenomas are characterized by dermal lobules composed of neoplastic sebocytes with an architecture vaguely resembling normal sebaceous lobules [4]. It has been proposed that two unique subtypes of sebaceous adenomas are highly specific markers for MTS: cystic sebaceous adenoma and sebaceous adenoma with an architectural pattern or combined features of keratoacanthoma. In fact cystic sebaceous neoplasms have thus far only been observed in patients with MTS, strongly supporting the view that they are highly specific markers for MTS [4,6].

Sebaceous carcinomas are very rare in occurrence and have the potential to arise from any sebaceous gland in the body. However, given the abundance of sebaceous glands, the ocular adnexa are the site with the highest predilection for these tumors. Unlike sebaceous adenomas, sebaceous carcinomas are fairly aggressive in nature, with the tendency for angiolymphatic invasion and subsequent metastatic disease [7]. Some authors suggest that extraocular sebaceous carcinomas (occurring mainly in the head and neck region but also on the external genitalia, trunk and extremities) are more indolent in nature than their ocular counterpart. Regardless, the propensity of these neoplasms to be invasive should prompt the clinician to evaluate for the presence of metastatic disease. Furthermore, all patients with an established diagnosis of sebaceous tumors should undergo a thorough evaluation for the presence of underlying Muir-Torre syndrome. This recommendation is based on a retrospective review of sebaceous neoplasms from the Mayo Clinic Department of Dermatology from 1923 to 1983. This study revealed that 42 percent of patients with one or more sebaceous neoplasms had at least one associated visceral malignancy consistent with the diagnostic criteria for Muir-Torre syndrome [8]. The temporal relationship between cutaneous lesions and visceral malignancies of MTS has also been closely studied. Skin manifestations of MTS appear to precede the diagnosis of visceral malignancy in 22 percent, concurrently in 6 percent, and afterward in 56 percent of cases [9].

The spectrum of internal malignancies of MTS is similar to that observed in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (i.e., HNPCC or Lynch syndrome). This autosomal dominant cancer predisposition syndrome is characterized by underlying germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes of affected families, leading to early onset of colorectal cancers and other associated tumors [10, 11]. A high proportion of MTS patients have germline mutations within two MMR genes, hMSH2 and hMLH1. This subset of MTS patients is now believed to represent a phenotypic (i.e., allelic) variant of HNPCC with associated skin tumors [12]. As was the case with our patient, the vast majority of the reported mutations have been shown to involve hMSH2, strongly supporting a genotype-phenotype correlation in MTS [11]. Because the underlying mechanism of tumorigenesis patients affected with MMR-deficient MTS exhibit tumors with high micro-satellite instability (MSI), which is also a characteristic feature of HNPCC-associated tumors [13].

While MSI analysis is widely appreciated as a screening technique for MMR-defective MTS, more recent studies have pointed to immunohistochemical analysis of tumor specimens for expression of hMSH2 and hMLH1 proteins as a useful and a more practical screening/diagnostic method. Mathiak et al. suggested that immunohistochemical staining, using antibodies against MSH2 and MLH1 proteins in MTS-associated skin tumors, is an extremely practical approach to diagnosis of the MMR-defective subtype of MTS. In their study, 17 of 19 (89 %) tumors from patients with MTS and a known germline mutation showed loss of MMR protein expression. Overall, the MMR protein expression pattern in 93% of skin tumors correlated with the molecular genetics results [14]. These results were in concordance with those of Entius et al. who examined sporadic sebaceous gland carcinomas for MSH2 and MLH1 expression and correlated the results of the immunohistochemistry with the MSI results [15]. In both studies loss of expression was found exclusively in patients with MSI-positive tumors.

One disadvantage of the immunohistochemical method is that the presence of hMSH2 and hMLH1 proteins does not exclude the possibility of an underlying DNA repair defect. For example, a missense mutation may lead to expression of a protein with an altered amino acid sequence leading to a false-negative result [13]. However, given the cost and time-effectiveness of this approach it should be considered the optimal method for confirmatory diagnosis of those suspected of having underlying MTS. Once a diagnosis of MTS is established surveillance for MTS-associated visceral and skin neoplasms is of utmost importance. Genetic counseling with systematic evaluation of the extended pedigree to identify other affected relatives is recommended.

References

1. Schwartz RA, Torre DP. The Muir-Torre syndrome: a 25-year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Jul; 33(1): 90-104. PubMed2. Akhtar S, Oza KK, Khan SA, Wright J. Muir-Torre syndrome: case report of a patient with concurrent jejunal and ureteral cancer and a review of literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999 Nov;41(5 Pt 1):681-6. PubMed

3. Cohen PR, Kohn SR, Kurzrock R. Association of sebaceous gland tumors and internal malignancy: the Muir-Torre syndrome. Am J Med. 1991 May;90(5):606-13. PubMed

4. Misago N, Narisawa Y. Sebaceous neoplasms in Muir-Torre syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000 Apr;22(2):155-61. PubMed

5. Burgdorg WH, Pitha J, Fahmy A. Muir-Torre syndrome: Histologic spectrum of sebaceous proliferations. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986 Jun;8(3):202-8. PubMed

6. Rutten A, Burgdorf W, Hugel H, Kutzner H, Hosseiny-Malayeri HR, Friedl W, Propping P, Kruse R. Cystic sebaceous tumors as marker lesions for the Muir-Torre syndrome: a histopathologic and molecular genetic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999 Oct;21(5):405-13. PubMed

7. Harrington CR, Egbert BM, Swetter SM. Extraocular sebaceous carcinoma in a patient with Muir-Torre syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2004 May;30(5):817-9. PubMed

8. Finan MC, Connolly SM. Sebaceous gland tumors and systemic disease: a clinicopathologic analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984 Jul; 63(4):232-42. PubMed

9. Lucci-Cordisco E, Zito I, Gensini F, Genuardi M. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and related conditions. Am J Med Genet A. 2003 Nov 1;122(4):325-34. PubMed

10. Mangold E, Pagenstecher C, Leister M, Mathiak M, Rutten A, Friedl W, Propping P, Ruzicka T, Kruse R. A genotype-phenotype correlation in HNPCC: strong predominance of msh2 mutations in 41 patients with Muir-Torre syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004 Jul; 41(7): 567-72. PubMed

11. Curry ML, Eng W, Lund K, Paek D, Cockerell CJ. Muir-Torre syndrome: role of the dermatopathologist in diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004 Jun; 26(3): 217-21. PubMed

12. Kruse R, Ruzicka T. DNA mismatch repair and the significance of a sebaceous skin tumor for visceral cancer prevention. Trends Mol Med. 2004 Mar;10(3): 136-41. PubMed

13. Mathiak M, Rutten A, Mangold E, Fischer HP, Ruzicka T, Friedl W, Propping P, Kruse R. Loss of DNA mismatch repair proteins in skin tumors from patients with Muir Torre syndrome and MSH2 or MLH1 germline mutations: establishment of a immunohistochemical analysis as a screening test. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002 Mar; 26(3): 338-43. PubMed

14. Entius MM, Keller JJ, Drillenburg P, Kuypers KC, Giardiello FM, Offerhaus GJ. Microsatellite instability and expression of hMLH-1 and hMSH-2 in sebaceous gland carcinomas as markers of Muir-Torre syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2000 May;6(5): 1784-9. PubMed

© 2006 Dermatology Online Journal