Extensive hypertrophic lichen planus in an HIV positive patient

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D34hj0g8h3Main Content

Extensive hypertrophic lichen planus in an HIV positive patient

Seyed Naser Emadi MD1, Jamal Akhavan-Mogaddam MD1, Maryam Yousefi MD2, Bahman Sobhani MD1, Abbas Moshkforoush MD1, Seyed Emad Emadi MR1

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (6): 8

1. Red Crescent Society of the Islamic Republic of Iran Research and Medical Center, Nairobi, Kenya. naseremad@yahoo.com2. Skin Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Individuals who are infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) suffer from numerous dermatoses. These disorders are often more severe than those observed in non HIV-infected persons afflicted with the same diseases. Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic inflammatory papulosquamous skin disorder. Herein, the diagnosis and treatment of a 40-year-old HIV+ Kenyan man afflicted with hypertrophic lichen planus (HLP) is described. In this case, lesions of HLP were widely distributed across the trunk and extremities, having become of such thickness on the dorsal surfaces of the hands and fingers as to make normal use of hands impossible. A significant distinguishing feature of this patient is prior history of tuberculosis, which is a known trigger for lichenoid skin lesions.

Introduction

The depletion of CD4+ T cells and the associated disruptions of immune homeostasis result in greatly elevated susceptibility to numerous pathologies in HIV positive persons. Among these disorders, certain dermatological conditions such as Kaposi sarcoma have emerged as hallmark presenting features of HIV infection. Infected persons also suffer from an elevated incidence and severity of dermatophytes, seborrheic dermatitis, Herpes simplex, Ofuji disease, psoriasis, molluscum contagiosum, and other dermatoses and infections [1]. Other syndromes affecting the skin are observed less frequently in patients with HIV.

The present report describes features of lichen planus (LP) in an HIV positive patient. LP is a chronic inflammatory papulosquamous dermatosis with characteristic clinical features that manifests as pruritic papules and plaques that may be accompanied by involvement of mucous membranes, nails and hair [2]. A few reports have described the onset of lichen planus lesions in the setting of HIV infection [3, 4, 5]. The subject of this report exhibited particularly severe LP including hypertrophic lesions widespread over the body. Description of clinical and laboratory findings and response to therapy presented here add to understanding of HIV-associated syndromes and their management.

Case history

The subject of this report is a 40-year-old Kenyan male referred to the dermatology unit of the Iranian Red Crescent Society in Nairobi-Kenya. He presented with widely distributed hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic patches and plaques with a slight violaceous hue on the face, lower lip, trunk, lower and upper limbs and the dorsal surfaces of both hands. (Figure 1). He also suffered from severe itching with prominent disability and limitation of mobility because of diffuse, hyperkeratotic, and thick epidermis on the dorsal hands and fingers (Figure 2). The patient reported the onset of the eruption in March 2008, first appearing on the dorsal surfaces of the hands and subsequently appearing on the other parts of the body.

Past medical and drug history

The intake interview with the patient noted a history of persistent pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) because of failure of treatment, for which he was provided treatment until 2005. A positive diagnosis of HIV was made in 2004, following which he was placed on a treatment regimen of HIV-targeted antiviral drugs including Triomune30 (Stavudine, Lamivudine, Nevirapine). The patient was also administered trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and multivitamin therapy. These treatments were initiated shortly following the diagnosis and were being continued at the time of this writing.

Until the time of his visits to the Iranian Clinic, Nairobi, the patient had not received treatment for the skin eruption, other than self-prescribed OTC products to control the itching.

Physical examination

The systemic examination of the head and neck, chest, limbs, and abdomen, including lymph nodes detected no abnormalities beyond the skin involvement described. Cutaneous examination revealed diffuse and convoluted hyperketrotic, hyperpigmented, patches, papules and plaques with a slight violaceous hue on the patient’s face, trunk, upper and lower extremities. The nails were slightly thin with longitudinal pigmented striata. Oral and genital membranes and hair were normal, with the exception of lesions on the lips (Figure 1).

Laboratory and radiological findings

- Hematology: Total white blood cells: 4000/mm³ (normal, at the low range); CD4+count: 140/mm³ (very low, reflecting HIV-mediated depletion of this subpopulation); hemoglobin 14.7g/dl (normal) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 60 mm/hr (elevated).

- Biochemistry: Alkaline phosphatase 513 units/L (high); and SGOT/AST 87 U/L (high).

- Urine analysis: Smear and culture were normal.

- ECG and Chest X-ray were normal

- Serology for VDRL, and Hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBs Ag) were negative. Also screening for Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) was negative. Serum HIV antibody evaluation by ELISA confirmed that the patient was HIV positive for type one.

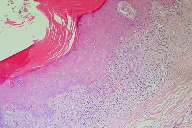

Histological examination

A biopsy was taken from the most recent lesion on the patient’s trunk. It revealed basket-weave type of hyperkeratosis. The epidermis was acanthotic with focal saw-tooth type of elongation of the rete ridges. Foci of basal layer degeneration were present with presence of an occasional colloid body. The upper dermis showed a round inflammatory cell infiltrate with numerous melanophages “hugging” the epidermis (Figure 3). On the basis of the clinical diagnosis and histopathological findings, the diagnosis of HLP was considered for the patient.

Treatment

The results of low CD4+ count (140/mm³) and elevated liver function tests raised concerns regarding hepatotoxicity of systemic drugs. He was understandably distressed and depressed by the inability to use his hands effectively because his livelihood depended on his manual work. Hence the HLP lesions were not treated with any medication except on the hands. Topical clobetasol was applied with occlusive plastic wrapping of the hands at night for six weeks. After six weeks treatment, the patient improved dramatically with reduced thickness and roughness of the skin on the dorsum of the hands (Figure 4). Eventually he was able to resume his normal duties with his hands.

Discussion

Lichen Planus may occur in immunocompromised hosts such as patients with graft versus host disease and abnormal humoral immunity. However, there are a few case reports of LP, especially a severely hypertrophic form, occurring as an associated feature of HIV infection [3, 4, 5]. The present case is unique because of the extensive and widespread distribution of disabling hypertrophic plaques of LP. Such widespread and severe lesions have been noted in other forms of HIV-associated dermatoses, including psoriasis vulgaris and seborrheic dermatitis, each of which is manifested in a more severe form in HIV-infected patients. Only rarely is LP so severe as was seen in our patient.

Keratotic forms (reticular and plaque) of oral LP occur in HCV seropositive patients more frequently than in seronegative patients [6]. This patient, however, was HCV negative, so this possibility is ruled out for the present case.

Another feature of this case that should be mentioned is that although the patient had elevated liver function test, he was hepatitis B antigen negative and HCV antibody negative. HBc, HBe and HBs antibodies were also negative. PCR for HBV DNA was done and showed a negative result. All of these tests were performed twice to definitely rule out an association with hepatitis B or C, known triggers for LP.

A related and very intriguing possibility is that one or more Mycobacterium Tuberculosis antigens may have acted as an immunogenic trigger for LP. The patient had a history of the disease and even if the symptoms were quiescent, some systemic distribution of its antigens would be likely [7, 8, 9].

Erbagci Z, et al. reported the case of a 52-year-old female with severe LP; and simultaneously a cutaneous form of TB, who was treated for the TB with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. The TB symptoms abated, but although no treatment specific for LP was administered, the lichenoid lesions vanished [10]. Removing the organism removes the antigen and eliminates the immune target, a theory that is speculative, but consistent with the observations.

Although several drugs have been shown to induce lichenoid lesions [11], sulfamethasoxazole is the only one reported (uncommonly) to do so of our patients medications, but this cannot absolutely be ruled out . Also the histological findings were not in favor of a drug induced lichen planus. Some antiretroviral drugs such as Zidovudin can induce oral lichenoid reactions in HIV disease [12], although our patient did not have any mucosal involvement.

Eczematous photosensitivity disorders have been reported in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. In one case report, a patient with advanced acquired immunodeficiency syndrome who developed photodistributed hypertrophic lichen planus was described. The authors believe this is a distinct cutaneous manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus infection [13]. Because we found an increased severity of involvement on the dorsal hands in comparison to the other parts of the body in this patient, this might be in part due to photoaggravation.

Systemic corticosteroids were not administered because of the anomalously low CD4 count. Plastic occlusion of superpotent corticosteroid of the LP lesion-affected areas was used for patient. This therapeutic strategy, introduced in the early 1960s and can enhance the utilization of topical corticosteroids. Drug delivery can be improved as many as 100 times when the area is covered with a plastic wrapper [14].

In summary, the outstanding features of the above case include:

1. Association of HIV, HLP, and past history of pulmonary tuberculosis

2. Severity and Widespread distribution of the HLP lesions

3. Severity of the lesion on the dorsal of the hands in comparison to the other parts of the body

4. Lack of HCV and HBV positivity which are known triggering factors for lichen planus.

References

1. Sadick NS, McNutt NS, Kaplan MH. Papulosquamous dermatoses of AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 22:1270-5. [PubMed]2. Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen Planus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 25:593-619. [PubMed]

3. Rippis GE, Becker B, Scott G. Hypertrophic lichen planus in three HIV-positive patients: A histologic and immunological study. Cutan Pathol 1994; 21:52-8. [PubMed]

4. Fitzgerald E, Purcell SM, Goldman HM. Photodistributed hypertrophic lichen planus in association with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: A distinct entity. Cutis 1995; 55:109-11. [PubMed]

5. Pardo RJ, Kerdel FA. Hypertrophic lichen planus and light sensitivity in an HIV-positive patient. Int J Dermatol 1988; 27:642-4. [PubMed]

6. Daramola OO, Ogunbiyi AO, George AO. Evaluation of clinical types of cutaneous lichen planus in anti-hepatitis C virus seronegative and seropositive Nigerian patient. Int J Dermatol 2003; 42:933-5. [PubMed]

7. Nagy E, Mészáros C, Somlyói I. Scrofulous lichen following BCG vaccination Z Haut Geschlechtskr. 1972 Oct 15; 47(20):859-62. [PubMed]

8. Haas N, Czaika V, Sterry W. Keratosis lichenoides chronica following trauma. A case report and update of the last literature review Hautarzt. 2001 Jul;52(7):629-33. [PubMed]

9. Pellicano R, Palmas F, Leone N, Vanni E, Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S, Puiatti P, Marietti G, Rizzetto M, Ponzetto A. Previous tuberculosis, hepatitis C virus and lichen planus. A report of 10 cases, a causal or casual link? Panminerva Med. 2000 Mar; 42(1):77-81. [PubMed]

10. Erbagci Z, Tuncel A, Bayram N, Erkilic S, Bayram A. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis in a patient with long-standing generalized lichen planus: improvement of lichen after antitubercular polychemotherapy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006; 17(5):314-8. [PubMed]

11. DeRossi SS, Ciarrocca KN. Lichen planus, lichenoid drug reactions, and lichenoid mucositis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005 Jan;49(1):77-89. [PubMed]

12. Scully C, Diz Dios P. Orofacial effects of antiretroviral therapies. Oral Dis. 2001 Jul;7(4):205-10. [PubMed]

13. Fitzgerald E, Purcell SM, Goldman HM. Photodistributed hypertrophic lichen planus in association with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a distinct entity. Cutis. 1995 Feb;55(2):109-11. [PubMed]

14. Flowers FP. Topical corticosteroid use in a dermatologic practice: an algorithm for appropriate use. University of Florida Continuing Education Proceeding, November 1987, pp 4-9.

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal