Pityriasis rotunda

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D34d71x158Main Content

Pityriasis rotunda

Priya Batra MD, Wang Cheung MD, Shane A Meehan MD, Miriam Pomeranz MD

Dermatology Online Journal 15 (8): 14

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityAbstract

A 42-year-old man presented with asymptomatic, sharply-demarcated, round, scaly lesions on his forearms that had been present for several months. A skin biopsy specimen was consistent with pityriasis rotunda. Pityriasis rotunda is a disorder of keratinization, which is thought to be a form of acquired ichthyosis, a delayed presentation of congenital ichthyosis, or a cutaneous manifestation of systemic disease. Patients with pityriasis rotunda may be classified into one of two groups, which are based on ethnicity, number of lesions, family history, and association with systemic diseases. Treatment is challenging, but the use of lactic acid lotion and oral vitamin A has shown some promise.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

History

A 42-year-old man from the Republic of Guinea presented to the Dermatology Clinic at Bellevue Hospital Center in September, 2008, for evaluation of asymptomatic lesions on his forearms for several months. He denied having similar lesions in the past and did not have any known family members with this finding. Topical application of clobetasol ointment and lactic acid lotion resulted in minimal improvement, if any. A review of systems was negative for fever, chills, shortness of breath, headache, abdominal pain, or weight loss. A punch biopsy was obtained for further diagnosis.

Past medical history included urinary frequency, for which he is followed by the urology service with a negative work-up to date. His only medication is oxybutynin. He does not use tobacco or alcohol.

Physical Examination

Hyperpigmented, sharply-demarcated, round plaques with plate-like scale, up to 3.0 cm in diameter, were located on the forearms. No lesions were present on the trunk or lower extremities.

Laboratory data

A basic metabolic panel, liver function panel, rapid plasma regain test, and human immunodeficiency virus titer were all normal.

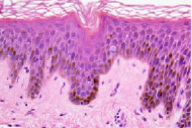

Histopathology

There is almost complete loss of the granular layer with slight spongiosis and a superficial, perivascular, lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Pigmentation of basal keratinocytes also is noted.

Comment

Pityriasis rotunda is a rare skin disease that is characterized by hyper- or hypopigmented, nummular, well-demarcated, scaly plaques that involve the trunk and extremities [1, 2, 3]. The condition was initially described in Japan by Toyama in 1906 and was termed tinea circinata [4, 5]. It is a disorder of keratinization that is frequently described among populations in Japan, South Africa, and the West Indies but is much less common in the Caucasian population, with only a few cases reported in the United States after 1985. Although most cases are sporadic, a familial occurrence among a cohort of 42 individuals in Sardinia was first reported in 1997 [6].

Patients often present with the characteristic lesions of pityriasis rotunda between the ages of 20 and 45 (range of 2 to 89) [4], except among the Sardinian cohort in which patients presented during childhood [6]. Incidence is equal among men and women. The disease lasts from several months to more than 20 years, with reports of exacerbation during winter months. The number of lesions may range from one to greater than 100, with a diameter that may exceed 20 centimeters in some cases [5].

The etiology of pityriasis rotunda remains unknown. Most authors believe that it is a form of acquired ichthyosis, a delayed presentation of congenital ichthyosis, or a cutaneous manifestation of systemic disease [1, 7]. In 1960, in a review of the literature, lung, liver, stomach, and other types of carcinoma were noted in 11 of 182 Asian patients [5]. In addition to neoplastic disease, approximately one-third of these patients had other underlying systemic diseases, which included malnutrition, tuberculosis, and cirrhosis. Several authors have linked pityriasis rotunda to leprosy, liver diseases, pulmonary diseases, multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia, and cardiac diseases, among many others [1, 5]. However, in studies of Caucasian patients, cutaneous findings have mostly occurred in the absence of underlying systemic diseases.

A classification has been proposed to encompass all reported cases of pityriasis rotunda [1]. Type I includes Black or Asian patients with fewer than thirty hyperpigmented lesions, nonfamilial incidence, and an association with malignant conditions or systemic diseases in 30 percent of cases. Type II occurs in Caucasian patients, and the lesions are usually hypopigmented, familial, numerous (greater than 30), and are not associated with a chronic illnesses. Since the development of this classification, there have been a few case reports that describe patients that display characteristics of both type I and type II [4].

Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes tinea versicolor, tinea corporis, nummular eczema, erythrasma, leprosy, fixed-drug eruption, pityriasis rosea, sarcoid, and pityriasis alba [5, 7, 8]. Histopathologic examination often shows hyperkeratosis, a thin or absent granular layer, increased pigmentation of the basal layer, pigment incontinence, and a sparse superficial, perivascular infiltrate. In some cases, the histopathologic appearance may be normal.

Treatment of pityriasis rotunda is a challenge, as topical glucocorticoids, antifungal agents, salicyclic acid, topical retinoids, and tars have shown no benefit [8]. Improvement in skin lesions has been noted after treatment with lactic acid lotion and oral vitamin A [9]. In patients with pityriasis rotunda that is associated with internal malignant conditions or systemic diseases, skin lesions have resolved upon successful treatment of the underlying disease [10, 11]. In the Sardinian cohort, resolution of disease occurred in 40 percent of children by the time they reached puberty [4, 6].

References

1. Grimalt R, et al. Pityriasis rotunda: report of a familial occurrence and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:866 [PubMed]2. Finch JJ, Olson CL. Hyperpigmented patches on the trunk of a Nigerian woman. Arch Dermatol 2008;144:1509 [PubMed]

3. Mafong EA. Pityriasis rotunda. Dermatol Online J 2002;8:15 [PubMed]

4. Friedmann AC, et al. Familial pityriasis rotunda in black-skinned patients; a first report. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156:1365 [PubMed]

5. Griffin L, Massa M. Acquired Ichthyosis and pityriasis rotunda. Clin Dermatol 1993; 11:27 [PubMed]

6. Aste N, et al. Pityriasis rotunda: a survey of 42 cases observed in Sardinia, Italy. Dermatology 1997;194:32 [PubMed]

7. Aste N, et al. Case report: pityriasis versicolor mimicking pityriasis rotunda. Mycoses 2002;45:126 [PubMed]

8. Sarakany I, Hare PJ. Pityriasis rotunda (pityriasis circinata). Br J Dermatol 1964;76:223 [PubMed]

9. Waisman M. Pityriasis rotunda. Cutis 1986;38:247 [PubMed]

10. Etoh T, et al. Pityriasis rotunda associated with multiple myeloma J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:303 [PubMed]

11. Leibowitz MR, et al. Pityriasis rotunda: a cutaneous sign of malignant disease in two patienrs. Arch Dermatol 1983;119:607 [PubMed]

© 2009 Dermatology Online Journal