Dermatitis herpetiformis

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D32zt3s5dqMain Content

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Meredith K Kosann MD

Dermatology Online Journal 9(4): 8

From the Ronald O. Perlman Department of Dermatology, New York University

Abstract

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic, lifelong disease characterized both by symptomatic, characteristic skin lesions and by a gluten-sensitive, often asymptomatic, enteropathy. Cutaneous findings include intensely pruritic vesicles on symmetrical extensor locations. Treatment for disease may be pharmacologic agents or a gluten-free diet. Evidence for the genetic basis of disease has been elucidated.

Clinical summary

History.—A 65-year-old man presented to the Bellevue Hospital Center dermatology clinic approximately 4 years ago with a lifelong pruritic eruption. He described a scaly eruption with severe pruritus that has become worse over the last several years. Upon initial examination, a diagnosis of psoriasis was made, and he was treated with topical glucocorticoids and oral antihistamines. His clinical course continued to fluctuate, and a punch-biopsy specimen was obtained in December 2000, and a specimen for direct immunofluorescence was obtained in August 2001. After laboratory work was completed, he was given a prescription for dapsone. He did not take the medication because he preferred topical treatments.

Physical examination.—Erythematous patches and plaques with crusts and erosions and a few pustules were present in a symmetrical pattern on the elbows, knees, dorsa of the hands, upper back, and gluteal crease.

|

|

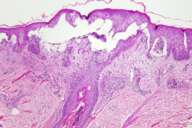

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

Laboratory data.—White-cell count was 9.2 x 109/L, hemoglobin 13.4 g/dL, and the platelet count 287 x 109/L. A quantitative measurement of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was 2.8U (normal range 3.5-5.0). Basic metabolic profile and hepatic function tests were normal.

Histopathology.—There are partially confluent, subepidermal vesicles with intravesicular neutrophils. The vesicles are centered at tips of dermal papillae. There is parakeratosis and focal single necrotic keratinocytes in the overlying epidermis. There is a mixed, perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and a few eosinophils.

Diagnosis.—Dermatitis herpetiformis.

Comment

Dermatitis herpetiformis was initially described over 100 years ago. Onset of disease is usually between ages 25-35, and the condition persists throughout life. Case studies of disease occurring in children have been reported. Clinically, the disease is characterized by intensely pruritic blisters that are distributed predominantly on the elbows, knees, buttocks, and scalp. The cutaneous findings exist in tandem with gastrointestinal disease; fewer than 10 percent of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis have symptoms of celiac disease, but all have a gluten-sensitive, often asymptomatic, enteropathy.

Diagnosis based on history and physical examination and may be confirmed by histology and direct immunofluorescence studies. Confirmatory laboratory findings may also be obtained. A recent study evaluating sera from 145 patients demonstrated that the level of imunoglobulin A autoantibodies to endomysium in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis was significantly elevated above controls [1].

First-line pharmacologic treatment for dermatitis herpetiformis is dapsone. Dapsone effectively controls skin findings and pruritus but may be associated with dose-related adverse effects such as hemolytic anemia, and idiopathic adverse effects such as neuropathy. Strict elimination of gluten from the diet also may prevent cutaneous disease, however, in practice the diet is restrictive and difficult to follow.

There is evidence for a genetic basis of this disease. Dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac disease have been associated with class II HLA alleles A1*0501 and B1*02, which encode the HLA-DQ2 heterodimer.[2] A study of almost 1,000 patients with dermatitis herpetiformis found that almost 11 percent of patients had an affected first-degree relative affected with either dermatitis herpetiformis or celiac disease in the same proportion.[3] Research to elucidate the relationship between skin and gastrointestinal disease is in progress. Recent studies have noted an upregulation of metalloelastase in both intestinal and lesional skin.[4] Investigators suggest that these findings are associated with T-cell-mediated immune responses with modulation of macrophage migration and degradation of proteoglycans or basement-membrane components in the subepithelial mucosa.

References

1. Dietrich W. et al. Antibodies to tissue transglutaminase as serologic markers in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol 1999;113:133.2. Spurkland A, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac disease are both primarily associated with the HLA-DQ (A1*0501, B*02) or the HLA-DQ (A1*03, B2*0302) heterodimers. Tissue Antigens 1997;49:29.

3. Reunala T. Incidence of familial dermatitis herpetiformis. Br J Dermatol 1996;134:394.

4. Salmela MT, et al. Parallel expression of macrophage metalloelastase (MMP-12) in duodenal and skin lesions of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. Gut 2001;48:496.

© 2003 Dermatology Online Journal