Acroangiodermatitis of Mali in a patient with congenital myopathy

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D31nc4995fMain Content

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali in a patient with congenital myopathy

Rashmi Jindal MD1, Dipankar De MD1, Sunil Dogra MD1, Uma Nahar Saikia MD2, Amrinder J Kanwar MD FAMS1

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (7): 4

1. Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprology2. Department of Histopathology

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. ajkanwar1948@gmail.com

Abstract

Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma is a disease entity that encompasses acroangiodermatitis as well as Steward-Bluefarb syndrome. It has varied etiologies and clinical presentations. Most important distinction is from Kaposi sarcoma and this is mainly histopathological. Here we report a case of acroangiodermatitis in a patient with congenital myopathy and have also discussed its pathogenesis.

Introduction

The term acroangiodermatitis of Mali was introduced for the first time by Mali et al. in 1965 who described 18 patients having mauve colored macules and papules predominantly over the extensor surface of feet with underlying chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) [1]. In 1967, morphologically similar lesions were described independently by Stewart as well as by Bluefarb and Adams on the legs of patients with arterio-venous malformations (AVM) [2]. This was termed the Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome. The term, pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma, is generally used synonymously with acroangiodermatitis of Mali, but is a broader term and includes both acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome. Both of these are characterized by reactive vascular proliferation and fibrosis. This benign entity should be recognized and differentiated from Kaposi sarcoma in the era of HIV/AIDS. Here we report a case of acroangiodermatitis of Mali in a patient with congenital myopathy. To the best of our knowledge this is the first case report of such an association.

Case report

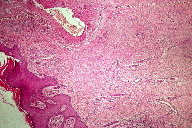

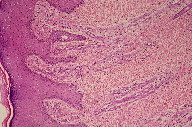

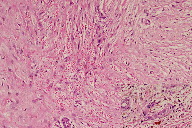

A 21-year-old wheelchair bound male, a known case of congenital myopathy-Nemaline type, attended presented with multiple coalescing violaceous plaques and nodules over the right foot that involved the dorsum and ankle region. There were surrounding pin-point to larger violaceous macules (Figure 1). Similar macules were present over the left ankle. There was no audible bruit or palpable thrill and no limb length discrepancy to suggest an AVM clinically. These plaques had started as small, flat, purple spots over both ankles six years previously; they extended to involve the dorsum of feet. Lesions over the right foot progressed in size and number, eventually attaining the present proportion. There were episodes of bleeding and ulceration following trauma that usually healed spontaneously in 3-4 months. Multiple treatment courses with topical antibiotics were of no use. Routine hematological and biochemical laboratory investigations were normal. Serology was negative for HIV. Doppler ultrasound showed no underlying AVM or CVI. A skin biopsy was sent for histopathological examination; the differential diagnosis of acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Kaposi sarcoma were considered. Histopathology revealed expansion of the capillary bed that showed reduplication and corkscrewing as well as erythrocyte extravasation, fibrosis, and hemosiderin deposit (Figures 2, 3, and 4). No atypical cells or vascular slits were present. Thus, the histopathology confirmed acroangiodermatitis of Mali.

Discussion

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome have similar clinical presentations and therefore are included under pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. The predominant cause of Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome is underlying congenital AVM. On the other hand acroangiodermatitis of Mali is reported in patients with CVI, paralyzed extremities, amputation stumps (especially with suction socket lower limb prosthesis), and iatrogenic A-V fistula [3]. A few cases have been described in association with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, homozygous activated protein C resistance, and carriage of a thrombophilic 20210A mutation in the prothrombin gene [4, 5, 6]. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome are both characterized by reactive vascular proliferation. In Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, the high perfusion pressure and oxygen saturation lead to neo-vascularization and fibroblast proliferation, whereas in acroangiodermatitis associated with CVI, endothelial cell proliferation results from tissue hypoxia and elevated venous pressure as a result of venous stasis [7]. Our patient was wheelchair bound because of a rare type of congenital myopathy known as Nemaline myopathy. This is characterized by stable or slowly progressive muscle weakness and hypotonia with or without respiratory insufficiency and cardiac involvement [8]. Our patient had progressive muscle weakness and hypotonia since birth but there was no respiratory or cardiac involvement. Severe chronic venous stasis and failure of the calf muscle pump could have resulted in the elevated capillary pressure causing reactive vascular proliferation and clinically presenting as lesions of acroangiodermatitis.

The clinical findings of pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma depend on the particular underlying etiology. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome presents in early life with unilateral purple blue macules and papules, which may ulcerate at times. The involved limb may show increase in length or girth and an audible bruit or a thrill may be felt. Acroangiodermatitis from CVI is usually bilateral and starts as purple colored macules, which enlarge to form soft, non-tender papules, nodules, and plaques with surrounding areas showing features of stasis dermatitis. Skin biopsy is required; Kaposi sarcoma is the most important item in the differential diagnosis. Histopathology in the Mali variant shows an increased number of thick walled vessels lined by plump endothelial cells, erythrocyte extravasation, and hemosiderin deposits predominantly in the upper half of the dermis. In Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome, the entire dermis gets involved and, in large specimens, an A-V shunt may also be seen. Late lesions in both forms show lobular proliferation of vessels separated by connective tissue septa, hemosiderin deposits, erythrocyte extravasation, and fibrosis. These vessels are round and regular, unlike Kaposi sarcoma, and also lack atypia. In Kaposi sarcoma, thin endothelial cell lined, irregular jagged blood vessels align pre-existing vessels. There are characteristic vascular slits and polymorphous hyper-chromatic spindle cells, which help in making the diagnosis. Further confirmation is with immune-histochemistry. In Kaposi sarcoma, both endothelial cells and perivascular spindle cells are CD34+, whereas in pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma perivascular cells completely lack CD34 expression. The proliferating fibroblasts in pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma are positive for antifactor XIIIa antibody. Apart from these, plethysmography, Doppler ultrasound, and arteriography may help in identifying underlying AVM [3].

Therapeutic options for pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma are limited and should be directed toward the primary disorder. External compression is thought to be the best method, which can be combined with topical antibiotics and corticosteroids [9]. Surgical excision of a shunt is curative in cases with AVM and patients with CVI may benefit from the use of compression stockings and vein sclerosis. The importance of identifying this disorder lies in differentiating it from true Kaposi sarcoma.

References

1. Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acroangiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol 1965 Nov;92(5):515-8. [PubMed]2. Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. Stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi's disease. Arch Dermatol 1967 Aug;96(2):176-81. [PubMed]

3. Trizna Z, Rapini RP. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma (Acroangiodermatitis) [online]. 2009 [cited 2009 Feb 19]

4. Lyle WG, Given KS. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma) associated with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Ann Plast Surg 1996 Dec;37(6):654-6. [PubMed]

5. Scholz S, Schuller-Petrovic S, Kerl H. Mali acroangiodermatitis in homozygous activated protein C resistance. Arch Dermatol 2005 Mar;141(3):396-7. [PubMed]

6. Martin L, Machet L, Michalak S, Delahousse B, Gruel Y, Vaillant L et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a carrier of the thrombophilic 20210A mutation in the prothrombin gene. Br J Dermatol. 1999 Oct;141(4):752. [PubMed]

7. Dogan S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: A challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatology Online Journal. 2007 Jul 13;13(3):22. [PubMed]

8. Sharma MC, Gulati S, Atri A, Seth R, Kalra V, Das TK et al. Nemaline rod myopathy: A rare form of myopathy. Neurol India 2007 Jan-Mar;55(1):70-4. [PubMed]

9. Lugovic L, Pusic J, Situm M, Buljan M, Bulat V, Sebetic K et al. Acroangiodermatitis (Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2007;15(3):152-7. [PubMed]

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal