S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A negative primary melanoma

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D31f36f917Main Content

S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A negative primary melanoma

Michi Shinohara MD1, Heike Deubner MD2, Zsolt B Argenyi MD3

Dermatology Online Journal 15 (9): 7

1. University of Washington Division of Dermatology2. Harborview Medical Center and University of Washington Department of Pathology

3. Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. mshinoha@u.washington.edu

Abstract

The diagnosis of malignant melanoma can be challenging given the wide variation in morphologic features and immunohistochemical stains are often used to confirm the diagnosis. We report a case of melanoma with loss of staining for S100 protein, HMB-45, and Melan-A, with retained expression of tyrosinase. Regional lymph node metastases showed positive S100 protein staining. Although the loss of phenotypic markers including S100 protein has been reported in metastatic melanoma, loss of S100 in primary melanoma is rare. Discordant staining between primary and metastatic lesions further emphasizes the protean nature of melanoma.

Introduction

Melanoma has a diverse range of morphologic presentations, and can demonstrate features of tumors from other lineages, ranging from smooth muscle to epithelial origin [1, 2]. Immunohistochemistry has been long applied as an adjunct tool that can aid in the diagnosis of difficult cases. Useful markers include S100 protein, which is highly sensitive, as well as HMB-45, MART-1/Melan-A, tyrosinase, and MITF, which are generally more specific [3].

Melanoma may differentially express detectable antigens at various phases of growth [4]; observing a loss of antigens in the transition from primary to metastatic lesions is not uncommon. The loss of S100 protein expression is less frequent compared to the more specific antigens (HMB-45, Melan-A), but occurs in up to 4 percent of metastatic melanomas, as well as in exceptional cases of primary melanoma [5]. Conversely, some tumors may gain expression of aberrant antigens [6]. We report a case of melanoma with retention of tyrosinase but loss of expression of S100 protein, HMB-45, and Melan-A, further complicated by differential staining of melanocyte specific antigens in local regional lymph node metastases.

Case report

A 62-year-old man presented with an enlarging, painful, 7 cm ulcerated tumor of the right temple. According to his history, a pigmented skin lesion had been present in this location since childhood, which had been enlarging for the past 7 years and intermittently bleeding. The patient reported that the lesion had initially been similar in appearance to two other irregular brown patches on his shoulders that had been present for 20 years. He had delayed seeking medical care for the growing mass due to a general avoidance of physicians.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Large ulcerated tumor of the right temple Figure 2. Atypical pigmented lesions of the left (A) and right (B) shoulders | |

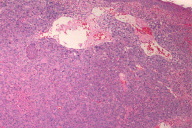

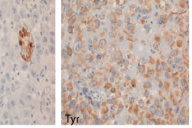

Initial biopsies of the large tumor showed no epidermal involvement, but replacement of the dermis with sheets of atypical epithelioid cells with pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and high mitotic activity. The morphologic features were not specific and a poorly-differentiated carcinoma, melanoma, or other epithelioid neoplasm were considered. Given the undifferentiated nature of the neoplastic cell population, a broad immunohistochemical panel was applied. Melanocytic markers including S100 protein, HMB-45, Melan-A, and MITF were negative; however, tyrosinase was positive with appropriate internal and external controls. Markers for carcinoma, vascular, and hematopoetic neoplasms (cytokeratins/epithelial membrane antigen, CD31, and CD30/45 respectively) were negative. CD68 was diffusely and weakly positive. The diagnosis based on the history, morphology, and immunohistochemical stains was most consistent with malignant melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 5 mm and Clark's level >IV (assuming a primary tumor).

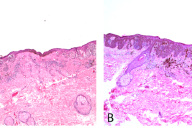

Excisional biopsies of the two pigmented lesions on his shoulders showed proliferation of atypical melanocytes predominantly along the dermal-epidermal junction and occasional nests in the dermis in both specimens, consistent with invasive melanoma arising in nevi. Breslow depths measured 0.57 mm (left shoulder) and 0.65 mm (right shoulder). HMB-45 and Melan-A performed on the left shoulder lesion were strongly positive (not shown).

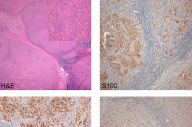

The patient underwent excision of the remaining large tumor mass as well as right selective lymph node dissection of levels 2, 3, and 5. The large tumor excision specimen showed sheets of atypical epithelioid cells replacing the dermis, again with no epidermal involvement and no apparent satellitosis. Nodules of tumor cells nearly replacing the normal lymph node architecture were found in 2 out of 14 regional lymph nodes and the region of the right parotid gland. Immunohistochemical analysis of the metastatic tumor population showed diffuse, strong S100 protein, HMB45, MITF, and tyrosinase staining. Melan-A was negative. PET scanning showed multiple bony and pulmonary lesions, consistent with metastases. The patient underwent palliative radiation and chemotherapy, and died within 6 months of diagnosis. No autopsy was performed.

Discussion

This case presented unique difficulties in diagnosis, with an unusually large tumor showing an aberrant immunophenotype. The loss of individual melanoma antigens including the differentiation antigens MART-1/Melan-A, HMB-45, and tyrosinase is relatively common, particularly in metastatic lesions [3, 7]. In contrast, the loss of multiple concordant antigens is rare, but has been reported in metastatic lesions [8]. Primary melanomas can lose expression of melanoma specific antigens, with the absence of HMB-45 in the majority of desmoplastic melanomas a prime example [1].

Although loss of staining for S100 protein in melanoma can occur in areas of extensive necrosis [9], S-100 remains the most sensitive marker for tumors of melanocytic origin, with reported sensitivities of 97-100 percent [3]. Loss of S100 expression in viable tumor cells, when it does occur, is much more common in metastatic lesions [10] but has been observed in rare cases of primary melanoma [5]. S-100 is highly sensitive but has lower specificity (75-87%) compared to the differentiation antigens MART-1/Melan-A and tyrosinase [3]. The reported specificity of tyrosinase antibody in particular is very high at 97-100 percent [3].

Our case is also distinctive due to the differential expression of melanoma antigens in the large tumor and lymph node metastases, with apparent "gain" of expression of several antigens including S-100 protein and HMB-45. Due to the advanced presentation, there was no absolute way to establish with certainty an epidermal component of the large ulcerated tumor. Despite this, it reasonable to assume that it was indeed a primary melanoma rather than a metastatic lesion because of the clinical history of a preceding long standing pigmented lesion (spanning decades). Metastatic lesions to the adjacent parotid gland and lymph nodes with identical cellular morphology further corroborate this argument. Although loss of antigen expression in metastases is common, there are no well-documented cases reported that have demonstrated absence of multiple melanoma antigens in a primary melanoma with preservation of these antigens in the lymph node metastases. One possible explanation is that the tumor cell population in the lymph nodes was established early, before the majority of the primary tumor lost antigen expression. Because of the unusually large size of the primary tumor specimen (9 cm), it was technically difficult to stain the entire lesion and there remains the possibility of tumor cells expressing the other melanoma markers in regions that were not tested.

In addition to the loss of S100 protein staining, an aspect of our case that deserves brief discussion is the presence of CD68 immunostaining in both the large tumor mass and the lymph node metastases. CD68 is a glycoprotein characteristically present in cells of macrocyte/macrophage lineage. The specificity of CD68 has been called into question, as it can be detected in some lymphomas, renal cell carcinoma, and up to 70 percent of melanomas reported in one series [11].

In summary, we report an unusual case of melanoma demonstrating loss of several melanoma antigens including S100 protein, HMB-45, MART-1/Melan-A and MITF with retention only of tyrosinase. Although tyrosinase is reported to be less sensitive than S100 protein for the identification of cells of melanocyte lineage, it is one of the most specific immunostains, that in the right morphologic setting remains an integral tool to aid in the diagnosis of melanoma. The possibility of aberrant immunophenotypic expression should always be considered when the clinical and morphologic manifestations are discrepant.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Marcia Usui for her excellent technical help with generation of the figures.

References

1. Magro CM, Crowson AN, Mihm MC. Unusual variants of malignant melanoma. Modern Pathology. 2006 Feb;19 Suppl 2:S41-70. [PubMed]2. Banerjee SS, Eyden B. Divergent differentiation in malignant melanomas: a review. Histopathology. 2008 Jan;52(2):119-29. [PubMed]

3. Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, Binder SW. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008 May;35(5):433-44. [PubMed]

4. Trefzer U, Hofmann M, Reinke S, Guo YJ, Audring H, Spagnoli G, Sterry W. Concordant loss of melanoma differentiation antigens in synchronous and asynchronous melanoma metastases: implications for immunotherapy. Melanoma Res. 2006 Apr;16(2):137-45. [PubMed]

5. Argenyi ZB, Cain C, Bromley C, Nguyen AV, Abraham AA, Kerschmann et al. S-100 protein-negative malignant melanoma: fact or fiction? A light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994 Jun;16(3):233-40. [PubMed]

6. Banerjee SS, Harris M. Morphologic and immunophenotypic variations in malignant melanoma. Histopathology. 2000 May;36(5):387-402. [PubMed]

7. Zubovits J, Buzney E, Yu L, Duncan LM. HMB-45, S-100, NK1/C3, and MART-1 in metastatic melanoma. Hum Pathol. 2004 Feb;35(2):217-23. [PubMed]

8. Gao Z, Stanek A, Chen S. A metastatic melanoma with an unusual immunophenotypic profile. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007 Apr;29(2):169-71. [PubMed]

9. Nonaka D, Laser J, Tucker R, Melamed J. Immunohistochemical evaluation of necrotic malignant melanomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007 May;127(5):787-91. [PubMed]

10. Aisner DL, Maker A, Rosenberg SA, Berman DM. Loss of S100 antigenicity in metastatic melanoma. Hum Pathol. 2005 Sep;36(9):1016-9. [PubMed]

11. Gloghini A, Rizzo A, Zanette I, Canal B, Rupolo G, Bassi P, Carbone A. KP1/CD68 expression in malignant neoplasms including lymphomas, sarcomas, and carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995 Apr;103(4):425-31. [PubMed]

© 2009 Dermatology Online Journal