Fissure leishmaniasis: A new variant of cutaneous leishmaniasis

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D30cf6q723Main Content

Fissure leishmaniasis: A new variant of cutaneous leishmaniasis

Arfan u Bari MBBS MCPS FCPS, Arfan ul Bari MBBS MCPS FCPS, Amer Ejaz MBBS MCPS FCPS

Dermatology Online Journal 15 (10): 13

CMH, Peshawar, Peshawar, NWFP PakistanAbstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) may appear at unusual sites or present with atypical morphologies. The lip is considered one of the unusual sites and a fissure of the lower lip is an atypical morphology that has not been described in CL. We report two cases of CL who presented as cutaneous fissures (on lower lip in one patient and dorsum of finger in another). They were diagnosed by demonstrating leishmania parasites in skin smear preparations and were treated accordingly.

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a parasitic disease caused by different species of Leishmania and is transmitted by sand fly bites [1]. The disease, once thought to be endemic in some regions of Pakistan, has now grown into an epidemic in the country [2, 3]. It usually affects the unclothed parts of the body at the site of a sandfly bite. After an incubation period of less than two months in L. major and more than two months in L. tropica, a red furuncle-like papule appears that gradually enlarges in size over a period of several weeks and assumes a more dusky violaceous hue. It eventually becomes crusted with a shallow underlying ulcer and indurated borders. Healing usually takes place in 2-6 months in L. major infection and 8-12 months in L. tropica, with a scar that is typically atrophic, hyperpigmented, and irregular [1, 3, 4]. The host's immune responses are important for protection against or elimination of parasites. On one end of the spectrum of CL is the classical oriental sore in which spontaneous cure and immunity to reinfection is the result of an effective parasiticidal mechanism. On the other end of the spectrum is diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis in which metastatic cutaneous lesions develop and the patient rarely, if at all, spontaneously develops immunity to the parasite [5, 6].

In recent times, there has been an increase in the number of reports for new and rare variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis both in the Old and the New World [7, 8]. In atypical forms of the disease, lesions either appear at unusual sites or present with atypical morphology. The lip is one of the atypical sites for CL and lesions primarily or solely involving lips are occasionally reported in adults [8, 9].

We report here one patient with lip leishmaniasis who presented with s fissure on the lower lip. A similar fissure morphology was seen on the dorsum of a finger in another case. Both were treated satisfactorily with intralesional injections of meglumine antimonite.

Case reports

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

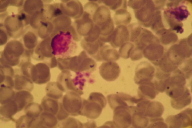

Case 1. A young soldier (28 years of age) presented with a 10-week history of a painless wound on his lower lip. It started as small ulcer in the center of the lip that gradually extended vertically and assumed the shape of a fissure (Fig. 1). It was not painful and all he could feel was a little discomfort because of overlying dried crust. There was no history of bleeding or purulent discharge from the lesion; submental lymph nodes were not palpable. He was otherwise in a good state of health. Microbial culture of the lesional tissue did not reveal any growth. Laboratory examination including complete blood count, blood chemistries, and urine examination were within normal limits. Because the patient originated in an endemic area of cutaneous leishmaniasis, he was suspected to have the disease in an unusual form and was subjected to cytodiagnostic tests for CL. From the edge of the lesion, a skin impression (touch) smear was made and fine needle aspiration for cytological examination (FNAC) was done. The impression smear was negative for leishmania parasites but the FNAC was able to demonstrate LT (Leishmania trophozoite) bodies (Fig. 2). Hence no further confirmation by skin biopsy or parasite culture was needed and he was on started weekly intralesional injections of meglumine antimonite, 300 mg/ml for a total of 0.5 ml at each treatment. Both edges of the fissure were infiltrated until blanched. After 8 weekly injections the fissure healed completely and there was no recurrence in the following six months (Fig. 3).

|  |

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|

|

| Figure 5 |

|---|

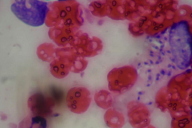

Case 2. A 23-year-old female presented with an 8-week history of swelling of the proximal phalanx of her middle finger along with a horizontal slit wound. It started as a small erythematous papule on the dorsum of the middle finger and developed a transverse fissure within. A plaque gradually enlarged in size and the fissure persisted (Fig. 4). The lesion was neither painful nor discharging. There was no history of any similar lesions over the hand or forearm. She was in a good state of health and routine laboratory examinations were with in normal limits. Skin slit smear (SSS) and FNAC were performed and this time SSS demonstrated LT bodies (Fig. 5). She was started on weekly local infiltration with intralesional injections of meglumine antimonite, 300 mg/ml for a total of 0.5 ml at each treatment. Both edges of the fissure were infiltrated until blanched. After 8 weekly injections the fissure healed completely.

Discussion

The clinical picture in leishmaniasis depends not only on the infecting Leishmania species, but also on the host immune response, which is largely mediated through cellular immunity. Other factors that affect the clinical picture include the number of parasites inoculated, site of inoculation and nutritional status of the host [3, 5, 6]. Cutaneous leishmaniasis may appear at unusual sites or present with atypical morphologies. Lesions at unusual sites are considered to be due to chance bites of sandflies at these sites, whereas disease at expected sites but having atypical morphology are probably due to altered host immune responses.

In recent times, there has been an increase in the number of reports for new and rare variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis both in Old and the New World [7, 8]. The lip is not considered to be one of the common sites for CL. In the medical literature, involvement of the lip is mostly described as part of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and lesions primarily affecting lips have not been mentioned frequently. Morphologically, lip lesions can be furuncle-like, nodular, chancriform, or psoriasiform plaques [8, 9].

Fissures of the lower lip have been described as a manifestation of staphylococcal infection [10], but in our patient (Case 1) microbial culture did not reveal growth of staphylococci nor was there any response to an anti-staphylococcal antibiotic (cloxacillin). Slit skin smear was positive for Leishmania trophozoite (LT) bodies and the patient responded satisfactorily to intralesional treatment with meglumine antimonite.

The precise pathogenesis of preferential lip involvement and subsequent appearance of the fissure morphology could possibly be due to a chance bite of the sandfly exactly at center point of lower lip. The horizontal fissure caused by CL in our second patient can be explained on the basis of the structural anatomy of skin on the dorsum of the fingers; the fissured configuration of the cutaneous lesions may relate to the presence of horizontal dorsal skin lines.

To the best of our knowledge, these are the first cases of CL presenting as fissures, giving rise to a new morphological variant of CL that may be named as "Fissure Leishmaniasis." Considering the increasing spectrum of CL in endemic areas, a high clinical suspicion should always be observed to make the diagnosis while lesions are small and institute an early and effective treatment.

References

1. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med 2003; 49:50-4. [PubMed]2. Bari AU. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2006; 16: 156-62.

3. Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, Saravia NG. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet 2005; 366(9496): 1561-77. [PubMed]

4. Ghosn SH, Kurban AK. Leishmaniasis and Other Protozoan Infections. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA. Paller AS, Leffell DJ. Eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol. 11, 7th ed. Mcgraw Hill Inc. 2008: 2001-9.

5. Rahman SB, Bari AU. Cellular immune host response in acute cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Col Phys Surg Pak 2005; 15: 463-6. [PubMed]

6. Bari AU, Rahman SB. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview of parasitology and hosp-parasite-vector interrelationship. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2008; 18: 42-8.

7. Calvopina M, Gomez EA, Uezato H, Kato H, Nonaka S, Hashiguchi Y. Atypical clinical variants in New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: Disseminated, Erysipeloid and Recidivia cutis due to Leishmania panamensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73: 281-4. [PubMed]

8. Bari AU, Rahman SB. Many faces of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74: 23-7. [PubMed]

9. Veraldi S, Rigoni C, Gianotti R. Leishmaniasis of the lip. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002; 82: 469-70. [PubMed]

10. Evans CD, Highet AS. Staphylococcal infection in median fissure of the lower lip. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 1986; 11: 289-91. [PubMed]

© 2009 Dermatology Online Journal