Scleroderma

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D304q484tpMain Content

Scleroderma

Paul J. Frank,MD

Dermatology Online Journal 7(1): 16

Department of Dermatology, New York UniversityPATIENT: 46-year-old man

DURATION: Two and one-half years

DISTRIBUTION: Head, neck, and extremities

History

In 1997, the patient began to develop progressive loss of hair and pigment of the head, neck and extremities. The diagnoses vitiligo and alopecia areata were made. There had been complaints of painful joints a few years prior that were treated as bursitis. In time, he noticed swelling and tightening of his face and hands and difficulty swallowing. In addition, there were subjective temperature changes in his fingers associated with color changes. A diagnosis of scleroderma was made, and he was placed on colchicine 0.6 mg daily and nifedipine 30 mg daily.

After a skin biopsy and further evaluation in the Charles C. Harris Skin and Cancer Pavilion in June, 1998, colchicine was replaced with azathioprine 25 mg daily that was subsequently increased to 150 mg daily. In May, 1999, thalidomide 100 mg daily was added to his regimen. The symptoms stabilized and slowly improved over the last two years with decreased tightness and partial repigmentation of the skin. During his course of treatment, he developed blind-loop syndrome and was placed on long-term treatment with doxycycline.

Physical examination

On initial examination, large patches of depigmentation and alopecia were present on the head, neck and distal extremities with follicular repigmentation. There was sclerodactyly of the hands with ulcers on several fingertips.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

Laboratory data

A complete blood count, chemistry profile, liver and thyroid function panels, C3, C4, and C-reactive protein were normal. Anti-Scl-70, anti-Sm, and anti-dsDNA antibodies were negative. Anti-RNP antibody and rheumatoid factor were negative. Antinuclear antibody was positive with nucleolar (1:128) and speckled (1:320) patterns. A full-body computed tomography scan, echocardiogram, and gallium lung scan were normal.

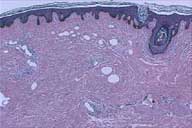

Histopathology

There was a square-shaped biopsy with thick collagen bundles in a hypocellular reticular dermis and a mild perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells at the dermal-subcutaneous junction.

Diagnosis

Scleroderma

Comment

Scleroderma is a chronic disease of the connective tissues and microvasculature. It is characterized by progressive fibrosis and obliteration of vessels in several organs, which include the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and heart.[1,2,3]

Clinical manifestations depend on the sites of involvement but often include Raynaud's phenomenon, chronic, nonpitting edema of the hands and fingers, and a migratory polyarthritis. Usually skin changes precede visceral involvement by several years.

Over time, skin findings progress toward sclerodactyly. Alopecia, anhidrosis, hyperpigmentation, and hypopigmentation may develop at involved sites and are thought to be postinflammatory responses. Long term complications of the skin include atrophy, recurrent painful ulcers of the fingertips, contractures, resorption of bone, and cutaneous calcification. Systemic complications include dysphagia and esophageal dysfunction, intestinal dysmotility and malabsorption, and the sequelae of pulmonary, cardiac, and renal fibrosis.[2]

Three main areas have been suspected in the pathogenesis of scleroderma: vascular endothelial damage, immunologic and inflammatory processes, and the dysregulation of extracellular matrix metabolism.[4,5,6] The consistent findings of autoimmune antibodies suggest their involvement in its pathogenesis and offer some value as prognostic indicators. Most consistently associated with systemic sclerosis is the Scl-70 autoantibody, which is directed against topoisomerase I.

Treatment of scleroderma remains unsatisfactory.[7] Immunosuppression with agents such as azathioprine, chlorambucil, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide has had limited success. Cyclophosphamide may be useful in the treatment of lung fibrosis. Colchicine, thalidomide, extracorporeal photophoresis, IFN-alpha, and D-penicillamine have shown some promise in the treatment of aggressive disease. Peripheral vasospasm may be alleviated with vasodilators such as diltiazem. Esophagitis and intestinal dysfunction may respond to H2 antihistamines, motility stimulants, and broad-spectrum antibiotics for bacterial overgrowth.

References

1.Briggs D, Black C, Welsh K. Genetic factors in scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1990;16:31-51. PubMed2.Sjogren RW. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum1994;37:1265-82,1994. PubMed

3.Mitchell H: Scleroderma and related conditions. Med Clin North Am 1997;81(1):129-49. PubMed

4.Sollberg S, Krieg T. New aspects in scleroderma research. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1996;111:330-336. PubMed

5.Casciola-Rosen L, Wigley F, Rosen A. Scleroderma autoantigens are uniquely fragmented by metal-catalyzed oxidation reactions: implication for pathogenesis. J Exp Med 1997;185(1):71-9. PubMed

6. Peng SL, Fatenejad S, Craft J. Scleroderma: a disease related to damaged proteins? [news] Nat Med 1997;3(3):276-8. PubMed

7. Denton CP, Black CM. Scleroderma and related disorders: therapeutic aspects. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2000;14(1):17-35. PubMed

© 2001 Dermatology Online Journal