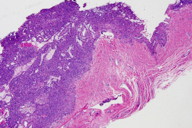

Figure 2. Well-circumscribed tumor composed of small vascular spaces surrounded by uniform round cells, glomus cells.

Glomus tumors (GT) are rare, soft-tissue tumors commonly found on the extremities. Because these tumors occur most often in the subungual region, they can be confused with other subungual pathologies including melanoma. Subungual GTs have a unique presentation and history but biopsy is diagnostic. Various imaging techniques are useful in diagnosis and management. We describe a classical case of subungual GT and discuss its presentation, diagnosis, management, as well as “atypical” or “malignant” variants.

|

|

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|---|

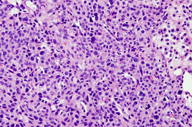

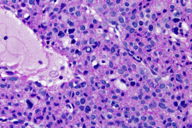

| Figures 3 and 4. Numerous round glomus cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclear pleomorphism surrounding vascular spaces. | |

A 63-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 1-year history of a painful growth on his right index finger (Figure 1). The patient stated that he first noticed a dark spot under his nail that progressively enlarged causing pain and overlying deformity. The patient denied any trauma to the finger but stated that there was severe pain precipitated by cold water and touch. Physical examination of the right index finger revealed a 1.8 cm x 0.8 cm flesh-colored tumor extruding through the proximal nail plate and extending subungually to the distal nail with associated longitudinal groove of the nail plate. The tumor was exquisitely tender to palpation. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any weight loss, night sweats, or lymphadenopathy. An excisional biopsy was performed and revealed a well-circumscribed tumor (Figure 2) composed of small vascular spaces surrounded by uniform round cells with striking nuclear pleomorphism and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figures 3 and 4).

Subungual glomus tumor is an exquisitely painful, rare neoplasm derived from the glomus body. The normal glomerular apparatus, first described by Hoyer in 1877, is a neuromyoarterial structure that functions in temperature homeostasis. GTs are composed of smooth muscle cells, vasculature structures, and glomus cells – specialized smooth muscle cells derived from pericytes [1-10]. They are categorized into 2 clinical forms: solitary and multiple. Solitary GTs, which account for 90 percent, are sporadic, occur during adulthood, are more common in women, and are usually found in the upper extremities. On the other hand, multiple GTs are autosomal dominant, occur in younger patients, are more common in men, and are non-painful. GTs are further subcategorized into 3 histological variants: solid glomus (most common), glomangiomas, or glomangiomyomas depending on the predominant tumor component [10]. Atypical or malignant forms, although extremely rare, do exist.

Glomus tumors are uncommon, comprising 1.6 percent of 500 consecutive soft-tissue tumors reported from the Mayo Clinic and represent approximately 1 percent to 5 percent of hand tumors [1, 10]. Clinically described in 1924 by Masson, GTs present with a subungual violaceous papule or nodule and resultant dystrophic nail. Patients commonly exhibit a triad of symptoms including excruciating paroxysmal pain, sensitivity to cold, and severe point tenderness [10]. Whereas they have been described in all age groups, subungual GTs are usually diagnosed during young adulthood. They are typically solitary and are found predominantly in the subungual region, where there is the highest concentration of glomus bodies. The pain produced by these neoplasms is often well out of proportion to their size. The mechanism of pain in GTs has not been fully established, but it may be related to contraction of myofilaments in response to temperature changes, leading to an increase in intracapsular pressure [2, 10]. Although the exact pathogenesis of GTs is unknown, it is proposed that they either represent harmatomas or reactive hypertrophy secondary to trauma [10].

Clinical examination, history, and imaging aid in the diagnosis of GTs, but biopsy is definitive in distinguishing it from common entites in the differential diagnosis, which include subungual exostosis, neuroma, ganglion, eccrine spiradenoma, melanoma, and leiomyoma [10, 11]. In the absence of classical symptoms, clinical tests with sensitivities and specificities over 90 percent including the Love (probing tumor with instrument reproduces pain), Hildreth (tourniquet applied to the arm reduces pain), cold-sensitivity, and transillumination tests can be performed [10]. In addition, radiographs may be helpful if they reveal a small scalloped osteolytic defect with a sclerotic border in the terminal phalanx, which is a highly characteristic finding of GTs and epidermal inclusion cysts in this location [3]. Depending on the histological variant, glomus cells (solid glomus), vascular structures (glomangiomas), or vascular structures and smooth muscle cells (glomangiomyomas) may be predominant. In addition, an increase in nerve and mast cells may be observed. Cytological pleomorphism is usually inconspicuous. Immunohistochemically, neoplastic glomus cells are positive for CD34, smooth-muscle actin (SMA) and muscle-specific actin, and may also be focally positive for desmin [10]. Vimentin staining, though neither specific nor sensitive, is commonly positive in malignant counterparts [11].

Because the surgical field is small, surgical management of GTs is challenging. However, it is the gold standard of treatment and is curative when the tumor is completely excised. Medical treatment is indicated for symptomatic pain relief only. Conservative excision utilizing transungual or lateral approaches is often attempted to preserve the nail matrix to avoid permanent nail deformity [4, 5]. Postoperative scars, paresthesia, and nail dystrophy are potential complications [4, 5]. If the presentation is unusual, a biopsy may be required to make the diagnosis prior to formal excision. If not completely excised, these tumors are likely to recur [6]. In a retrospective study of 75 GTs with clinical follow-up ranging from 1 to 20 years, GTs located below the nail matrix were found to be at substantial risk for recurrence (17%). To reduce the risk of recurrence, imaging modalities including standard X-rays, arteriograms, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound, may be employed to delineate the extent of the tumor before surgery [7, 8].

Occasionally GTs may display unusual features, such as large size, deep location, infiltrative growth, mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, and necrosis. In 2001, Folpe et al. [9] reviewed 52 “atypical” or “malignant” GTs and evaluated tumor size, depth, growth pattern, cellularity, nuclear grade, number of mitotic figures per 50 high-power fields (HPF), atypical mitotic figures, vascular space involvement, and necrosis to define criteria for malignancy. Follow-up revealed 7 recurrences, 8 metastases, and 7 related mortalities. Five-year cumulative metastatic risk increased significantly for tumors with a deep location, a size of more than 2 cm, and atypical mitotic figures. Mitotic activity of more than 5 mitoses/50 HPF, high cellularity, the presence of necrosis, and moderate to high nuclear grade approached but did not reach significance. High nuclear grade alone, infiltrative growth, and vascular space involvement were not associated with metastasis [9]. In our patient, other than for the striking nuclear pleomorphism, no other atypical feature was identified; there was only one mitotic figure (not atypical) identified in the entire lesion and necrosis was not seen. In addition, the tumor was superficial and its size was less than 2 cm in greatest dimension. The tumor was excised without incident or recurrence at 2-year follow-up.

© 2011 Dermatology Online Journal