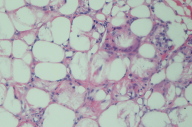

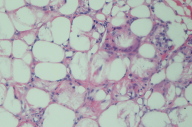

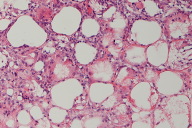

Figures 2 - 4. Biopsy of the right back

We report a case of subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn (SCFN), a rare disorder in term or post-term neonates. Although it is often associated with hematological abnormalities such as anemia and hypercalcemia, SCFN in this patient presented with hyperbilirubinemia. The course of SCFN is generally benign and self-limiting, though may be associated with complications secondary to hypercalcemia.

|

|

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

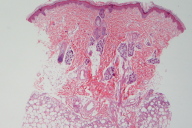

| Figure 1. Back of the newborn at 5 days of life Figures 2 - 4. Biopsy of the right back |

|

|

|

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|

A 5-day-old term newborn presented with a small, firm, erythematous plaque on her back and shoulders. Birth history was significant for simple vaginal delivery with Group B strep colonization treated at delivery and terminal meconium. On day 2 of life, the patient developed hyperbilirubinemia of 12.6 mg/dL, decreasing to normal levels over the next week without treatment. Biopsy taken from the right back (Figures 2 - 4) showed a lobular panniculitis with an infiltrate of mixed inflammatory cells. Needle shaped clefts, in radial array, are seen in adipocytes and giant cells.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis is a rare disorder that occurs in term or post-term neonates. Typical lesions include smooth, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules or plaques located on the cheeks, shoulders, back, buttocks, or thighs. Lesions usually develop within the first weeks of life and regress over the following weeks without treatment.

Although the etiology of SCFN is unclear, subcutaneous stress e.g. hypoxemia, leading to adipocyte necrosis may be a critical step in the pathogenesis. Maternal predisposing risk factors include gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, cocaine use, smoking, calcium channel blocker use during pregnancy, and thrombosis. Hypothermia, hypoxemia, infections and cutaneous trauma during delivery, as well as newborn anemia and tendency for thrombosis are also implicated [1].

Subcutaneous fat necrosis is generally benign. However, complications associated with it may cause long-term sequelae and even mortality. The most serious metabolic complication, hypercalcemia, may take up to 6 months to develop after the onset of skin lesions [2]. Common clinical presentation ranges from no symptoms, to lethargy, hypotonia, vomiting, polyuria, dehydration, and failure to thrive. In severe cases, metastatic calcification occurs in kidneys, myocardium, major vessels, liver, and brain, compromising these organs' function and even causing organ failure. Management includes i.v. normal saline, loop diuretics, and low calcium and vitamin D formula. Cases resistant to these measures can be treated with corticosteroids, bisphosphonate, and calcitonin. Serum calcium level needs to be monitored at least biweekly for up to 6 months or until resolution of fat necrosis.

Thrombocytopenia may present before or along with skin lesions. It lasts up to several weeks and resolves spontaneously, though platelet transfusion may be necessary [3]. Hypoglycemia may occur in SCFN infants born to diabetic and nondiabetic mothers. It precedes skin lesions and resolves spontaneously within several weeks [4]. Hypertriglyceridemia may develop after skin lesions and lasts until the lesions resolve [5]. In addition, lactic acidosis, anemia, and hyperferritinemia have all been described in SCFN infants [6, 7, 8].

Included in the differential diagnosis for SCFN is sclerema neonatum (SN), a panniculitis affecting ill preterm neonates in the first week of life. Unlike SCFN, which is local and self limiting, SN rapidly generalizes and carries a grave prognosis with 75 percent mortality. Newborns with SN may present with mask-like facies or “pseudotrismus” secondary to the thickening of the skin over the face, arms and hands [9].

On histology, the two entities differ in their level of inflammation. Sclerema neonatum typically shows minimal inflammation on biopsy, with normal epidermis and dermis and needle-shaped crystals arranged radially in adipocytes [10]. Subcutaneous fat necrosis characteristically has needle-like clefts in histiocytes, although they may be seen less commonly in adipocytes as well [11]. The crystals are formed from triglycerides of stearic and palmitic acids, which make up the panniculus of the neonate [12]. Some authors argue that the presence of crystals on histology should not be used to distinguish between SCFN and SN, suggesting that clinical presentation and level of inflammation on histology be used instead for diagnosis [10].

The case of SCFN we present cleared without scarring or other sequelae over the next six weeks. Since that time, the child has reached all age-appropriate developmental milestones and continues to develop normally on the growth curve.

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal