|

|

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

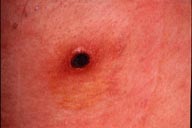

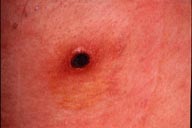

| Figure 1: Axillary eschar. Figure 2: View of the chest demonstrating the multiple erythematous macules.

Tsutsugamushi disease (scrub typhus) is an acute infectious disease caused by Rickettsia tsutsugamushi transmitted through the bite of larvae of certain trombiculid mites (chiggers). This disease has been recognized for more than a hundred years on the northern Honshu island of Japan as a serious endemic disease.(1) It is also seen in Southeast Asia, Indonesia, India, and Nepal. All age patients may be involved. Presumably, anyone bitten by a Rickettsia-infected mite may become infected. Key diagnostic features include the presence of an eschar, high fever, lymphadenopathy, and the rash. Patients may develop elevated liver function tests due to hepatic involvement. Differential diagnosis includes drug reactions and viral exanthem. Treatment is usually initiated with tetracycline 1 gm/day or doxycycline 200 mg/day for seven days. The response usually occurs within three to four days. Incomplete treatment is usually followed by a reappearance of the disease. Fatal cases appear to be rare and are probably due to inappropriate antibiotic treatment. Untreated patients may die of disseminated intravascular coagulation. The classic tsutsugamushi disease occurs during the summer, has a high mortality rate, and is transmitted by Leptotrombidium akamushi. The so-called new type of tsutsugamushi disease has been increasing in almost all parts of Japan since 1976, although this type of disease is milder than the classic one. Annual registered cases to the Ministry of Health and Welfare have reached 800 recently.(2) This new tsutsugamushi disease is seen from autumn to spring and is transmitted by L. pallidum or L. scutellare. One of the reasons that tsutsugamushi disease has increased recently in Japan is that the first choice of antibiotics has changed.(3) Tetracycline and chloramphenicol, which were highly effective against tsutsugamushi disease, have been generally replaced with penicillins and cephalosporins in the treatment of infectious disease. The banning of pesticides such as DDT and BHC has allowed an increase in vector mite colonies and may have contributed to this phenomenon.(2) After the bite of chigger larva, the primary lesion enlarges in size and undergoes central necrosis which becomes an eschar within one or two weeks. The illness begins suddenly with headaches and fever along with the maturation of an eschar. This is followed by a skin rash resembling roseola or rubella. If an eschar is found, tsutsugamushi disease is diagnosed easily. However, it resembles also drug reaction eruption. If the correct diagnosis and the proper treatment are not available, the prognosis is serious. Twenty fatal cases were reported from 1977 to 1989 in Japan.(4) The clinical diagnosis of tsutsugamushi disease can be confirmed by demonstrating an antibody elevation to R. tsutsugamushi antigens, including complement fixation test, indirect immunofluorescent antibody test, indirect immunoperoxidase test, and ELISA in which Karp, Gilliam, and Kato strains are usually used. Weil-Felix agglutination test is now thought to be neither very sensitive nor very specific.(5) Serodiagnosis usually takes time and late treatment may bring serious clinical outcome. When tsutsugamushi disease is suspected, empiric treatment with tetracycline or chloramphenicol should be considered. References1. Tamiya T: Recent advances in studies of tsutsugamushi disease in japan, Tokyo: Medical Culture Inc, 1962: 42.2. Kawamura A, Tanaka H: Rickettsiosis in Japan. Jpn J Exp Med 1988; 58:169-184. 3. Suto T: Recent tsutsugamushi disease and its rapid detecting method ( In Japanese). Jpn Med J 1982; 3034:43-49. 4. Takeshita T, Koga T: Tsutsugamushi disease in saga prefecture (English abstract). Nishinihon J Dermatol 1991; 53:60-64. 5. McDonald JC, MacLean JD, McDade JE: Imported rickettsial disease: clinical and epidemiologic features. Am J Med 1988; 85:799-805. |