Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (Schamberg's purpura) in an infant.

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D33qg9c0p1Main Content

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (Schamberg's purpura) in an infant.

A. Zvulunov,1 I Avinoach,2 L.Hatskelzon,3 S. Halevy.4

Dermatology Online Journal 5(1): 2

From the Department of Pediatrics, 1 Yoseftal Medical Center, Eilat, the Units of Dermatopathology2 and Hematology-Oncology3

and the Department of Dermatology, 4 Soroka Medical Center, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva,

Israel.Abstract

Purpura in an infant is usually an alarming sign of a systemic (infectious, hematologic-oncologic or immunologic) disease. Chronic purpuric dermatoses have not been reported in infants and, therefore, are not considered in the differential diagnosis of purpuras in this age. We report on a female infant with progressive purpura who underwent extensive laboratory investigations to rule out a systemic disease. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical course, the diagnosis of Schamberg's purpura was established.

Case Report

A 20 month old female infant was referred to us because of a purpuric rash that had started on the extremities 5 months prior to presentation. Gradually, the rash involved other skin areas. Fading of the purpuric rash was followed by residual hyperpigmentation. The parents were particularly concerned with facial involvement that had followed an ordinary episode of crying. There was no history of epistaxis or serious bleeding. The patient's past medical history was unremarkable, except for occasional episodes of acute otitis media. The infant was never exposed to steroidal or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and, except for occasional antibiotic treatments, did not receive any other medications. She was born at term after an uneventful pregnancy and was the first child to unrelated healthy parents. She had one 4 month old healthy brother. There was no family history of purpura.

On physical examination the patient appeared as a well-developed healthy infant. She had a patchy, poorly demarcated light-brown to reddish hyperpigmentation over the trunk and the extremities (Fig 1). On the thighs there were prominent purpuric macules (Fig 2). Tourniquet test was positive. On ophthalmologic examination the retinal blood vessels were normal and there were no retinal hemorrhages.

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Widespread reddish-brown macules on the trunk of the infant. | Cayenne-pepper-like purpura intermingled with hyperpigmented macules on the thighs. |

Routine laboratory tests that included ESR, CBC and SMA were all normal. Peripheral blood smear revealed normal platelets, few target-shaped and tear-drop-shaped erythrocytes, as well as anisocytosis with hypochromia. Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time were normal. Bleeding time (Ivy's method) was 4.5 seconds (normal). Platelet aggregation induced by adenosine-diphosphate, adrenaline, collagen and ristocetin were normal in the patient and both of her parents.

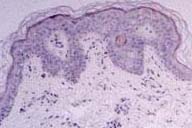

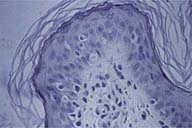

Punch skin biopsy, obtained from a recent purpuric macule on the left buttock, revealed perivascular mononuclear infiltrates with extravasated erythrocytes and few hemosiderin deposits in the upper dermis without apparent damage to vessel walls (Fig 3,4). Prussian Blue staining confirmed the deposition of hemosiderin. PAS staining revealed preserved vessel walls and basement membrane. No abnormality was observed with elastic fiber staining. On direct immunofluorescence there was no deposition of immunoglobulins, complement or fibrinogen in vessel walls. Electron microscopy showed normal ultrastructure of the skin.

The clinical and laboratory findings in our patient suggested the diagnosis of chronic pigmented purpuric dermatosis (Schamberg's purpura). Except for assurance and guidance of the parents, no specific therapeutic measures were advised. Currently, at the age of 5 years, new purpuric lesions continue to appear, mostly on the lower extremities, with subsequent widespread, yet uneven, hyperpigmentation of the skin.

Discussion

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses have been traditionally divided into 5 clinical entities: Schamberg's purpura (typically presenting as "cayenne pepper" spots on lower extremities), Majocchi's purpura (described as purpura annularis telangiectoides), lichen aureus (characterized by a solitary golden-colored patch with purpura), Gougerot-Blum purpura (typically presenting as lichenoid papules with purpura on lower extremities) and eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis (characterized by itching and orange-colored pigmentation).[1] These clinical entities are histologically indistinguishable and, probably, represent a spectrum of one disease.[2] The purpuric dermatoses are infrequently reported in preadolescent children and adolescents.[3-5] Until this report, the youngest patient with Schamberg's purpura was an 8-year-old girl.[5]

| Table 1. Differential diagnosis of purpura in infants. |

|---|

|

The clinical features in our patient fall within a group of pigmented purpuric dermatoses. Although the clinical manifestations do not perfectly fit any particular form of the pigmented purpuras, they conform most closely with Schamberg's purpura.

The differential diagnosis of chronic purpura in infancy is detailed in Table 1. The patient's history and routine laboratory tests allow exclusion of most of the listed entities. As a rule, laboratory investigations are unremarkable in the pigmented purpuras. The positive tourniquet test implies an increased capillary fragility that is attributed to capillary wall damage by perivascular inflammatory infiltrates. However, overt vasculitis is not usually observed.[6] Direct immunofluorescence is positive in about 700f cases, showing deposition of fibrinogen, IgM and/or C3 in superficial dermal vessels.[6]

The etiology of chronic pigmented purpuras is unknown although there are indications that immune mechanisms are involved. These include the deposition of immunoglobulins and/or complement around dermal vessels,[6] and modulation of cellular adhesion molecules in dermal endothelial cells and in lymphocytes in lesional skin.[7]

No effective therapy has been established for the chronic pigmented purpuras. Recently, successful treatment with griseofulvin,[8] pentoxifylline,[9,10] and with PUVA[11] have been reported in few patients. However, in view of the benign nature of the pigmented purpuras, the use of these therapies in infants and children is not justified.

In summary, the presented case demonstrates a rare cause of purpura in infancy. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of purpura in infants.

References

1. Champion R.H. Capillaritis of unknown cause. In: "Textbook of Dermatology", 5th edition R.H. Champion, J.L. Burton and F.J.G. Ebling, editors, Blackwell Scientific Publications (London) 1992; pp. 1888-1891.2. Smoller BR, Kamel OW. Pigmented purpuric eruptions: immunopathologic studies supportive of a common immunophenotype. J Cutan Pathol 1991;18:423-427.

3. Kahana M, Levy A, Schewach-Millet M et al. Lichen aureus occurring in childhood. Int J Dermatol 1985;24:666-667.

4. Kerem E, Branski D, Gross-Kieselstein E, et al. Chronic pigmented purpura: a case report of Schamberg's disease. Clin Pediatr-Phila 1987;26:657-658.

5. Draelos ZK, Hansen RC. Schamberg's purpura in children: case study and literature review. Clin Pediatr Phila 1987:659-661.

6. Ratnam KV, Su WPD, Peters MS. Purpura simples (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): A clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatl 1991;25:642-647.

7. Driesch P, Simon M. Cellular adhesion antigen modulation in purpura pigmentosa chronica. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:193-200.

8. Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol 1995;132:159-160.

9. Wahba-Yahav AV. Schamberg's purpura: association with persistent hepatitis B surface antigenemia and treatment with pentoxifylline. Cutis 1994;54:205-206.

10. Kano T, Hirayama K, Orihara M, Shiohara T. Successful treatment of Schamberg's disease with pentoxifylline. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:827-830.

11. Wong WK, Ratnam RV. A report of two cases of pigmented purpuric dermatoses treated with PUVA therapy. Acta Derm Venereol 1991;71:68-70.