Dowling-Degos Disease involving the vulva and back: Case report and review of the literature

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D38xq4s916Main Content

Dowling-Degos Disease involving the vulva and back: Case report and review of the literature

Mary E Horner MD1, Katherine E Parkinson MD2, Valda Kaye MD3, Peter J Lynch MD1

Dermatology Online Journal 17 (7): 1

1. University of California, Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, California2. Parkinson Dermatology, Spooner, Wisconsin

3. University of Minnesota Department of Dermatology, Plymouth, Minnesota

Abstract

Dowling-Degos disease is a rarely encountered pigmentary disorder in which small brown-to-black macules appear in a clustered or reticulated pattern primarily at flexural sites. It usually occurs as an autosomal dominant trait but sporadic cases have also been reported. Dowling-Degos disease is sometimes associated with other cutaneous abnormalities, many of which appear to occur as a result of abnormal follicular development. The histology is distinctive with marked, heavily pigmented, slender, and often branched, elongation of the rete ridges. Dowling-Degos disease is caused by one of several loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene. Similar mutations are found in patients with Galli-Galli disease and that disorder is now considered to be a subset of Dowling-Degos disease. Medical therapy is ineffective but two patients have responded well to ablative laser therapy. We report a patient with the sporadic form of the disease who developed pigmented macules in the rarely involved sites of the lower back and vulva. Her vulvar lesions were treated with Er:YAG laser ablation.

Introduction

Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) is an uncommon, benign disorder characterized by the presence of reticular pigmentation on flexural surfaces. The first description of the disease has generally been attributed to Dowling and Freudenthal when they differentiated what is now known as DDD from acanthosis nigricans in 1938 [1, 2]. However, depending on the definition used, even earlier reports may exist [1]. In 1974 Wilson Jones and Grice translated the French name for the disease “dermatose pigmentaire réticulée des plis” (as given earlier by Degos and Ossipowski) as “reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures” and thus this latter term is synonymous with that of DDD [2]. These same authors, in 1978, proposed the eponymous name of Dowling-Degos disease for the disorder [2]. Fewer than 50 cases had been reported by 1999 [3], but since then there have been approximately a dozen additional published reports. Our patient is quite unusual in having involvement of the vulva and lower back.

Report of a case

A 23-year-old light-skinned woman presented with dark brown vulvar macules that had first been noted at age 17. Subsequently she developed similar macules in the axillae, the popliteal fossae, and on the lower back. The lesions were asymptomatic. There was no family history for similar lesions. On examination, small (<5 mm) pigmented macules, occurring in clustered and somewhat reticulated patterns, were noted on the skin of the axillae, popliteal fossae, lower back, vulva, perineum, and perianal area. There was a tendency for confluence of the macules to occur toward the center of the clusters. The color of the lesions varied from light brown to brown-black. Very light scale was present over some of the lesions.

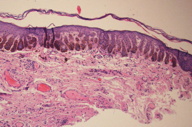

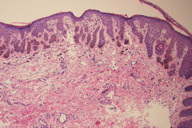

Biopsies were taken from the vulvar and perianal macules. The microscopic appearance was similar from both sites and showed overlying hyperkeratosis with elongation, branching, and deep pigmentation of the rete ridges. The pigmentation was appreciably denser in the lower third of the rete ridges. There was no apparent increase in melanocytes. A small keratin cyst was seen in one of the rete ridges. Mild dermal inflammation was accompanied by pigment in macrophages. Clinical pathological correlation led to a diagnosis of Dowling-Degos disease.

The patient was recalled for additional examination and at that point, no pigmented lesions were found on the buccal mucosa or on the dorsal hands and feet. In addition, there was no evidence of other cutaneous problems previously reported as occurring in patients with DDD. Specifically, there was no evidence of hidradenitis suppurativa, seborrheic keratoses, comedo-like lesions, hyperkeratotic follicular lesions, epidermoid cysts, pitted acne-like facial scars, or keratoacanthomas. She received Er:YAG laser therapy to the vulvar lesions; no follow-up is as yet available.

Discussion

1. Clinical presentation

Dowling-Degos disease may present in either a sporadic or an autosomal dominant manner [1, 2, 3]. Based on individual case reports and several case series it appears to be more common in women than in men [2, 3, 4, 5].

Initial lesions first appear in childhood or early adult life, although a few cases with onset at a later time have been reported. In most instances involvement at one site is followed by progression to other locations. The site most commonly involved is the axillae but frequently there is also involvement of the neck, popliteal fossae, and inframammary folds. Involvement of the antecubital fossae and the thighs is appreciably less common. Groin involvement is mentioned fairly frequently but specific description of genital involvement is very unusual. We found no previous reports of lesions on the lower back. In the vast majority of patients with DDD, the hyperpigmented macules are restricted to flexural sites but in a few instances, lesions have been noted on the dorsal surface of the hands, feet, and distal limbs. In even fewer cases, the lesions may be generalized [6].

Previous authors have stated that only a small number of patients with DDD involving the vulva had been identified. However, using Google Scholar in addition to Pub Med, we identified 16 published cases of DDD in which the vulva was involved [1, 5, 7-15]. In addition, we are aware of a Korean poster presentation regarding a patient with involvement of the vulva. Based on the fact that DDD seems to affect all other flexural regions it seems likely to us that vulvar involvement is more common than has previously been reported and that perhaps it is missed. The vulvar area may not have been examined by either the patient or her dermatologist.

The lesions of DDD are usually non-palpable macules 3 to 5 mm in diameter. The color may be light brown, dark brown, grey or black. Pigment intensity may increase as a patient ages. Rarely, the lesions are slightly elevated and, in unusual instances, the surface may have slight scale. Palpable lesions are more likely to be encountered in Galli-Galli disease, the acantholytic variant of DDD (see below). The pigmented macules of DDD are typically said to occur in a reticulated pattern. But perusal of the photos in previous reports indicates that for most patients the pattern is actually more clustered than reticulated. Confluence of macules, especially in the center of the patches, occurs in some patients. Once present, the pigmented lesions remain in place indefinitely. DDD is almost always asymptomatic, but pruritus has been reported in a few cases.

Associated findings in some patients have included facial (often perioral) acne-like pitted scars, hyperkeratotic follicular papules (usually on the neck and upper trunk), and large, dark comedones (face, neck, and upper back). Hidradenitis suppurativa has been reported in 16 patients, an association occurring frequently enough to suggest that a true relationship exists [16-20]. There are isolated reports of dappled hypopigmentation [6, 21], fingernail dystrophy [21], epidermoid cysts [2, 19], keratoacanthoma [22], and squamous cell carcinoma (arising in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa in two cases and in the dappled skin in one) [18, 21].

2. Histology

The microscopic findings in DD are distinctive and well documented. These are nicely summarized in two publications containing a total of 16 patients [2, 3]. The most notable feature is striking filiform elongation of the rete ridges (Figure 3). These narrow epithelial down growths are generally two to four cells wide. Branching of the rete ridges is common and, when marked, can result in an “antler-like” configuration (Figure 3). These epidermal changes primarily involve the surface epithelium but may also be found in the infundibular portion of adjacent hair follicles. Hyperpigmentation occurs mainly in the lower third of the elongated rete ridges where it is variable in density but is often quite intense (Figures 3 and 4). The number of melanocytes is not increased. Overlying mild hyperkeratosis is commonly present. Thinning of the suprapapillary epithelium is regularly present. The epidermis often contains small keratin-containing cysts, which may be numerous and mimic the appearance of an adenoid seborrheic keratosis (Figure 4). Sparse inflammatory cells and pigment-containing macrophages are found in the dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Follicular dilatation with or without follicular plugging may be present.

3. Pathogenesis

With rare exceptions [23, 24], DDD, in both familial and sporadic cases, is caused by at least three different loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene (KRT5) [25, 26]. In the few instances in which these mutations were not identified in the coding region of KRT5, it has been hypothesized that mutations either occurred in non-coding areas of KRT5 or that mutations in one or more other genes can cause DDD [24]. Interestingly, based on a limited number of cases, there may be a difference in the pattern and distribution of the pigmentation: mainly reticulated and flexural in those with the mutations and more widely distributed clustered macules in those without the mutation [24].

Because mutations in keratin 5 can cause epidermolysis bullosa of the simplex type (EBS), it is important to understand why there is no blistering in patients with DDD. In DDD the mutations occur in the ‘head’ region of one of the alleles of the KRT5 gene. This leads to inactivation of the gene (“null allele”) and the failure to produce an active gene product. This in turn leads to haplo-insufficiency. On the other hand, in EBS, the allelic mutations occur further downstream allowing for production of a gene product, but one that is dysfunctional. This dysfunctional product then adversely affects the product of the wild type allele. For polymeric molecules such as collagen, these “dominant negative” types of mutations are appreciably more deleterious than mutations leading to haplo-insufficiency. It is of appreciable interest that there is a rare type of EBS in which the patients develop both mottled pigmentation (somewhat similar to that which occurs in DDD) and the blisters that are characteristic of EBS. In these patients a KRT5 mutation in the head region on one allele accounts for the pigmentary change and a mutation further downstream in the other allele causes the blistering [27].

Electron photomicrographs of the keratinocytes in DDD show an abnormal distribution of the melanosomes that have been transferred from melanocytes. Specifically they are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm rather than, as in normal situations, lying tightly clustered as a “nuclear cap.” This suggests that keratin 5 likely plays a role in melanosome transport and localization in keratinocytes. This in turn, presumably accounts for the clinical presentation of hyperpigmentation [25, 26].

As was noted above, a variety of follicular abnormalities (pitted acne-like scars, hyperkeratotic follicular papules, large dark comedones, and hidradenitis suppurativa) occur in DDD. Based on this association we suspect that keratin 5 may also play a role in follicle development. This hypothesis is partially supported by the finding that a different mutation in the KRT5 gene leads to structural defects in hair follicles and sebaceous glands [28].

4. Differential diagnoses and relationship to other reticulated pigmentary disorders

Even though the clinical presentation of Galli-Galli disease is essentially identical to that of DDD, it has, until recently, been considered as a separate entity because of the presence of acantholysis on biopsy. However, a recent study found KRT5 mutations, identical to those identified in DDD, in five of seven unrelated patients with Galli-Galli disease [24]. Moreover, the authors carefully re-reviewed the histopathology of biopsies from six patients who had previously been diagnosed with DDD. They found evidence of acantholysis in all six patients and concluded that acantholysis is frequently missed in DDD [24]. Based on these data it seems appropriate to view these two diseases as identical [24, 29].

As reviewed by Wu and Lin, reticulated pigmentation on the dorsal hands and feet has been reported in a few patients with DDD and Galli-Galli disease [6]. Since this is the distribution pattern found in reticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura (RAPK), several authors have proposed that these are related disorders [30, 31, 32, 33]. The histopathology is very similar to that in DDD but clinically in RAPK palmar and plantar pits are present and there is slight depression of the pigmented lesions. Thus, whereas there is some overlap, the exact relationship between these two diseases will have to await mutational analysis of the KRT5 gene in RAPK.

Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (acropigmentation of Dohi, symmetrical dyschromatosis of the extremities) also presents with hyperpigmented macules on the dorsal hands and feet. In some cases there is facial involvement and proximal spread onto the limbs. Clinically, dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH) is distinguished from DDD and RAPK by earlier onset (infancy and early childhood) and the presence of intermingled hypopigmented macules [34]. Histologically, there is no elongation of the rete ridges similar to that characterizing DDD and the mutational defect occurs in an adenosine deaminase gene (ADAR1) rather than in a keratin gene. For this reason DSH and DDD are probably not related.

A very few cases of generalized DDD have been described [6, 35]. These patients may have intermingled hypopigmented macules and for this reason there is clinical overlap with dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria (DUH) [6, 35]. In the cases described by Wu and Lin, the histology at all sites was that of DDD, whereas, in the case biopsied by Sandhu, the trunkal lesions possessed the typical flattened epidermis typical of DUH [6, 35]. Moreover, at least for the recessive form of DUH, the mutational defect is on chromosome 12 in the region involving the ligand for the c-kit receptor rather than involving the KRT5 gene [36, 37]. What, if any, relationship exists between these two diseases remains controversial.

Other pigmentary disorders, such as acanthosis nigricans, Haber disease, and the various lentiginous syndromes that might be considered in the differential diagnosis of DDD overlap to a lesser degree and are fairly easy to differentiate on the basis of clinical and/or histological findings [1, 29]. See Table 1.

5. Treatment

No therapy has been established as effective. Previous reports indicate that topical steroids, hydroquinone, and oral retinoids are not effective. Topical retinoids have also not been effective for the most part but there is one report of improvement with adapalene [38]. Two patients appear to have been treated quite effectively with the erbiumYAG laser [39, 40].

References

1. Batycka-Baran, A., Baran W, Hryncewicz-Gwozdz A, Burgdorf W. Dowling-Degos disease: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology, 2010. 220(3): p. 254-8. [PubMed]2. Jones, E.W. and K. Grice, Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Dowing Degos disease, a new genodermatosis. Arch Dermatol, 1978. 114(8): p. 1150-7. [PubMed]

3. Kim, Y.C., Davis MD, Schanbacher CF, Su WP. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures): a clinical and histopathologic study of 6 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1999. 40(3): p. 462-7. [PubMed]

4. Crovato, F., G. Nazzari, and A. Rebora. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures) is an autosomal dominant condition. Br J Dermatol, 1983. 108(4): p. 473-6. [PubMed]

5. Mansur, A.T.G., Sevil; Uygur, Tulin; Akgun, Nilufer; Aker, Fugen. Dowling-degos disease: clinical and histopathological findings of 6 cases. Turkderm, 2004. 38(2): p. 126-133.

6. Wu, Y.H. and Y.C. Lin. Generalized Dowling-Degos disease. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2007. 57(2): p. 327-34. [PubMed]

7. Fernandez-Redondo, V., et al. [Dowling-Degos disease]. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am, 1990. 18(2): p. 96-100. [PubMed]

8. Jafari R, T.M., Vakilzadeh F. Morbus Dowling-Degos in Genitoperianal Localisation in a Mother and a Daughter. Aktyelle Dermatologie, 2003. 29(6): p. 240-242.

9. Korstanje, M.J.H., R-F.H.J.; van der Kley, A.M.J. Dowling-Degos disease associated with profuse lentigines. British Journal of Dermatology, 1989. 121: p. 529-530.

10. Massone, C. and R. Hofmann-Wellenhof. Dermoscopy of Dowling-Degos disease of the vulva. Arch Dermatol, 2008. 144(3): p. 417-8. [PubMed]

11. Milde, P., G. Goerz, and G. Plewig. [Dowling-Degos disease with exclusively genital manifestations]. Hautarzt, 1992. 43(6): p. 369-72. [PubMed]

12. O'Goshi, K., T. Terui, and H. Tagami. Dowling-Degos disease affecting the vulva. Acta Derm Venereol, 2001. 81(2): p. 148. [PubMed]

13. Punsoda, G.B., I.; Ribera, M.; Fernandiz, C. Enfermedad de Dowling-Degos: presentacion de tres casos conafeccion de la semimuscosa vulvar. Medicina cutanea ibero-lation-americana, 1995. 23(4): p. 187-190.

14. Sacerdoti, G., Amantea, A., Donati, P., Menaguale, G., Fazio, M. Dowling-Degos disease localized in the vulvar area. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 1996. 6(1): p. 62-64.

15. Schiller, M., Kutting B, Luger T, Metze D. [Localized reticulate hyperpigmentation]. Hautarzt, 1999. 50(8): p. 580-5. [PubMed]

16. Balus, L., Fazio M, Amantea A, Menaguale G. [Dowling-Degos disease and Verneuil disease]. Ann Dermatol Venereol, 1993. 120(10): p. 705-8. [PubMed]

17. Kleeman, D., R.M. Trueb, and P. Schmid-Grendelmeier. [Reticular pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Dowling-Degos disease of the intertrigo type in association with acne inversa]. Hautarzt, 2001. 52(7): p. 642-5. [PubMed]

18. Li, M., M.J. Hunt, and C.A. Commens. Hidradenitis suppurativa, Dowling Degos disease and perianal squamous cell carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol, 1997. 38(4): p. 209-11. [PubMed]

19. Loo, W.J., E. Rytina, and P.M. Todd. Hidradenitis suppurativa, Dowling-Degos and multiple epidermal cysts: a new follicular occlusion triad. Clin Exp Dermatol, 2004. 29(6): p. 622-4. [PubMed]

20. Dixit, R., George R, Jacob M, Sudarsanam TD, Danda D. Dowling-Degos disease, hidradenitis suppurativa and arthritis in mother and daughter. Clin Exp Dermatol, 2006. 31(3): p. 454-6. [PubMed]

21. Ujihara, M., Kamakura T, Ikeda M, Kodama H. Dowling-Degos disease associated with squamous cell carcinomas on the dappled pigmentation. Br J Dermatol, 2002. 147(3): p. 568-71. [PubMed]

22. Fenske, N.A., Groover CE, Lober CW, Espinoza CG. Dowling-Degos disease, hidradenitis suppurativa, and multiple keratoacanthomas. A disorder that may be caused by a single underlying defect in pilosebaceous epithelial proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1991. 24(5 Pt 2): p. 888-92. [PubMed]

23. Asahina, A., Ishii N, Kai H, Yamamoto M, Fujita H. Dowling-Degos disease with asymmetrical axillary distribution and no KRT 5 exon 1 mutation. Acta Derm Venereol, 2007. 87(6): p. 556-7. [PubMed]

24. Hanneken, S., Rutten A, Pasternack SM, et al. Systematic mutation screening of KRT5 supports the hypothesis that Galli-Galli disease is a variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol, 2010. 163(1): p. 197-200. [PubMed]

25. Betz, R.C., Planko L, Eigelshoven S, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene lead to Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet, 2006. 78(3): p. 510-9. [PubMed]

26. Liao, H., Zhao Y, Baty DU, McGrath JA, Mellerio JE, McLean WH. A heterozygous frameshift mutation in the V1 domain of keratin 5 in a family with Dowling-Degos disease. J Invest Dermatol, 2007. 127(2): p. 298-300. [PubMed]

27. Arin, M.J., Grimberg G, Schumann H, et al. Identification of novel and known KRT5 and KRT14 mutations in 53 patients with epidermolysis bullosa simplex: correlation between genotype and phenotype. Br J Dermatol, 2010. 162(6): p. 1365-9. [PubMed]

28. Sagelius, H., Rosengardten Y, Hanif M, et al. Targeted transgenic expression of the mutation causing Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome leads to proliferative and degenerative epidermal disease. J Cell Sci, 2008. 121(Pt 7): p. 969-78. [PubMed]

29. Muller, C.S., C. Pfohler, and W. Tilgen. Changing a concept--controversy on the confusing spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol, 2009. 36(1): p. 44-8. [PubMed]

30. Al Hawsawi, K., Al Aboud K, Alfadley A, Al Aboud D. Reticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura-Dowling Degos disease overlap: a case report. Int J Dermatol, 2002. 41(8): p. 518-20. [PubMed]

31. Cox, N.H. and E. Long. Dowling-Degos disease and Kitamura's reticulate acropigmentation: support for the concept of a single disease. Br J Dermatol, 1991. 125(2): p. 169-71. [PubMed]

32. Crovato, F. and A. Rebora. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures associating reticulate acropigmentation: one single entity. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1986. 14(2 Pt 2): p. 359-61. [PubMed]

33. Shen, Z., Chen L, Ye Q, et al. Coexistent Dowling-Degos disease and reticulate acropigmentation of kitamura with progressive seborrheic keratosis. Cutis, 2011. 87(2): p. 73-5. [PubMed]

34. Oyama, M., Shimizu H, Ohata Y, Tajima S, Nishikawa T. Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi): report of a Japanese family with the condition and a literature review of 185 cases. Br J Dermatol, 1999. 140(3): p. 491-6. [PubMed]

35. Sandhu, K., A. Saraswat, and A.J. Kanwar. Dowling-Degos disease with dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria-like pigmentation in a family. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2004. 18(6): p. 702-4. [PubMed]

36. Amyere, M., Vogt T, Hoo J, et al. KITLG Mutations Cause Familial Progressive Hyper- and Hypopigmentation. J Invest Dermatol, 2011. [PubMed]

37. Stuhrmann, M., Hennies HC, Bukhari IA, et al. Dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria: evidence for autosomal recessive inheritance and identification of a new locus on chromosome 12q21-q23. Clin Genet, 2008. 73(6): p. 566-72. [PubMed]

38. Altomare, G., Capella GL, Fracchiolla C, Frigerio E. Effectiveness of topical adapalene in Dowling-Degos disease. Dermatology, 1999. 198(2): p. 176-7. [PubMed]

39. Voth, H., Landsberg J, Reinhard G, et al. Efficacy of ablative laser treatment in galli-galli disease. Arch Dermatol, 2011. 147(3): p. 317-20. [PubMed]

40. Wenzel, G., Petrow W, Tappe K, Gerdsen R, Uerlich WP, Bieber T. Treatment of Dowling-Degos disease with Er:YAG-laser: results after 2.5 years. Dermatol Surg, 2003. 29(11): p. 1161-2. [PubMed]

© 2011 Dermatology Online Journal