Behçet syndrome

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D381f3k4djMain Content

Behçet syndrome

Ahmet Altiner MD, Rajni Mandal MD

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (11): 18

Department of Dermatology, New York University, New York, New YorkAbstract

We present a 34-year-old man with a two-year history of aphthous stomatitis, who later developed painful, erythematous nodules on his lower extremities. A pathergy test was positive, and the diagnosis of Behçet syndrome (BS) was made. It is important for the dermatologist to recognize the wide variety of cutaneous manifestations of this disorder. A pathergy test is a simple diagnostic tool that may assist in making a diagnosis. Case reports of other unusual skin manifestations in BS also are reviewed.

History

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

A 34-year-old man presented to Bellevue Hospital Center in 2006 with a five-month history of intermittent, recurrent, painful, oral ulcers. The diagnosis of a vitamin deficiency was made in the emergency room and multivitamins were given without improvement. The lesions on the tongue were painful but did not interfere with food intake. At the time of diagnosis, he denied other skin lesions, joint pains, headaches, gastrointestinal symptoms, or visual disturbances. A herpes simplex virus culture was negative. He was initially treated with topical glucocorticoids and silver nitrate sticks and later with colchicine without improvement.

In 2009, the patient presented with painful, erythematous nodules on the anterior aspects of the lower legs that were associated with subjective fevers. A biopsy specimen was obtained. A pathergy test was positive. Increasing doses of dapsone were initiated with a favorable response, but complete resolution had not been obtained.

Physical examination

On the tongue and buccal mucosae there were numerous ulcers. On the lower legs there were nodules with overlying hyperpigmented patches.

Laboratory data

A complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were normal. Negative serologies included anti-nuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-desmoglein antibodies, and syphilis antibody. Zinc levels were normal. A colonoscopy and esophogeogastroduodonoscopy were not consistent with Crohn disease.

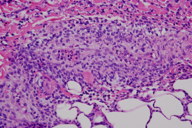

Histopathology

There is a dense infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes, which obscures the wall of a medium-sized vessel at the junction between the reticular dermis and subcutis.

Comment

Behçet syndrome (BS), which was named after the Turkish dermatologist Hulusi Behçet, is a multi-systemic, autoimmune disease that initially was described as the triple symptom complex of recurrent, oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, and sterile uveitis.

The diagnostic criteria have evolved considerably over the decades reflecting the complexity and diverse manifestations of this multiorgan systemic disease [1, 2]. In the United States, the International Guidelines for the Classification of Behçet Disease are generally accepted [3]. The criteria include recurrent oral aphthae (at least three episodes within 12 consecutive months plus two of the following: recurrent, genital ulcers; uveitis or retinal vasculitis; skin lesions that are classified as erythema nodosum (EN)-like lesions, acneiform lesions, pustulosis, or pseudofolliculitis; and a positive pathergy test. Increasing doses of dapsone were initiated with a favorable response, but complete resolution has not been obtained.

In addition to the diagnostic criteria, most patients with BS manifest disease in a variety of organ systems. Epidemiologic studies have shown that 8 to 20 percent of patients have vascular involvement, most notably venous occlusion [4]. Arthritis tends to present at an early age and the life-time risk of appreciable arthritis is 50 percent [5]. Neuro and pulmonary vasculitis, myocarditis, and hypopyon (a rare but almost pathognomonic manifestation of BS) also have been reported [6, 7].

Because there are no known serologic tests that are specific for BS, the diagnosis can be delayed. In the last decade, however, there has been an increased interest in searching for biomarkers that may assist in the recognition of BS and in monitoring the clinical response. Candidate markers include circulating endothelial cells (CEC) and antiendothelial cell antibodies [AECA] directed against them. In a study from China, sera from patients with BS showed that AECAs were found more commonly in patients with BS when compared to those with rheumatoid arthritis (p<0.01) but not with systemic lupus erythematosus [8]. In a study from Turkey, the presence of CECs in blood of patients with BS was higher in those with elevated disease activity [9].

Currently, the use of AECA and CEC is limited to research studies, so we still must depend on clinical presentation alone to accurately make a diagnosis. Particularly important to the dermatologist is the recognition of the diversity of skin manifestations. For example, in a study of 128 patients from Spain, nail-fold capillaroscopy was abnormal 40 percent of the time and enlarged capillaries often were linked to more severe vascular complications, which included hypertension and superficial phlebitis [10]. A case report from France highlighted the evolution of necrotizing folliculitis in a young man with BS. This observation emphasizes the diverse findings that comprise one of the minor diagnostic criteria [11].

Our patient’s most important manifestation was painful, aphthous ulcers. His features fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for BS (oral ulcers, EN-like lesions, and a positive pathergy test).

References

1. Misushima Y. [Revised diagnostic criteria for Behçet’s disease in 1987]. Ryumachi Feb 1988;28:66 [PubMed]2. Behcet H. Uber rezidivivierende, aphthose, durch ein Virus verusachte Geschwure am Mund, am Auge und and en Genitalien. Dermatol Wochenschr 1937;105:1152

3. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1990;335:1078 [PubMed]

4. Sechas MN, et al. Vascular manifestations of BeGmailhcet’s disease. Int Angiol 1989;8:145 [PubMed]

5. Kim NH, et al. Behçet’s arthritis. J Korean Orthop Surg 1993;8:145

6. Boe, J, et al. Mucocutaneous-ocular syndrome with intestinal involvement: a clinical and pathological study of four fatal cases. Am J Med 1958;25:857 [PubMed]

7. Kim DK, et al. Clinical analysis of 40 cases of childhood-onset Behçet’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol 1994;11:95 [PubMed]

8. Zheng, WJ, et al. A study of anti-endothelial cell antibodies in Behçet’s disease. Chinese Intern Med 2005;44:910 [PubMed]

9. Kutlay, S, et al. Circulating endothelial cells: a disease activity marker in Behçet’s vasculitis? Rheumatol Int 2008;29:159 [PubMed]

10. Movasat A, et al. Nailfold capillaroscopy in Behçet’s disease, analysis of 128 patients. Clin Rehumatol 2009;28:603 [PubMed]

11. Trad S., et al. Necrotizing folliculitis in Behçet’s disease. Rev Med Interne 2009;30:268 [PubMed]

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal