Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: A case report and review of the literature

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D33h66199vMain Content

Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: A case report and review of the literature

Brian P Kelley MD, Dornechia E George MD, Todd M LeLeux MD, Sylvia Hsu MD

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (8): 5

Department of Dermatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas. shsu@bcm.eduAbstract

Sarcoidosis is a potentially life-threatening, multisystem, granulomatous disease that can present with cutaneous manifestations in patients. A rare cutaneous manifestation of this disease may resemble acquired ichthyosis. We report a 45-year-old woman with a several year history of dyspnea on exertion and panuveitis who presented to a county hospital with acquired lower extremity ichthyosis and a biopsy consistent with both acquired ichthyosis and noncaseating, granulomatous sarcoidosis. To our knowledge, this entity has been described in only 22 previous independent cases, with the present case being 1 of only 5 cases to rapidly progress to full systemic involvement. Furthermore, it is important to recognize the manifestations of sarcoidosis in the skin, because these may be the presenting signs of systemic illness.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease that commonly involves the lungs, liver, eyes, skin, and lymph nodes, especially in people of African descent. Cutaneous involvement has been reported in approximately 20 to 35 percent of sarcoidosis patients [1], with up to 25 percent of patients exhibiting symptoms only in the skin [2]. Recognition of cutaneous signs of sarcoidosis is critical, considering that 96 percent of patients with these signs may be appropriately diagnosed within 6 months compared with 69 percent of patients lacking cutaneous signs [3]. Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, plaques, patches, nodules, ulcers, pustules, or localized alopecia. These are most commonly localized in the head and neck area or on the extensor surfaces of extremities. However, the lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis may occur asymmetrically or symmetrically on any skin or mucosal body surface. These lesions can serve as diagnostic signs, especially when associated with noncaseating granulomas in the dermis. A rare cutaneous form of sarcoidosis can resemble acquired ichthyosis. Acquired ichthyosis is often a manifestation of underlying systemic disease and has been associated with malignancy, endocrine and metabolic disease, as well as infection, drugs, and immunologic disorders.

Case report

|

| Figure 1 |

|---|

| Figure 1. Dry, scaly patches on the shin |

A 45-year-old woman with a past medical history of asthma and recurrent panuveitis was admitted to the hospital after complaining subjectively of fever, night sweats, weight loss, worsening dyspnea on exertion, and cramping lower abdominal pain. Previous encounters with ophthalmology had not warranted further investigation into systemic disease; however, the patient’s history was significant for markedly decreased visual acuity and eye pain in the 2 months prior to admission. Dermatology was consulted for the finding of asymptomatic, dry, scaly patches on bilateral extensor surfaces of the shins (Figure 1) and forearms. No other cutaneous manifestations were noted. Further physical exam demonstrated bilateral conjunctival injection and bilateral parotid enlargement. Lung and cardiac exams were reviewed as normal.

The patient was found to have hilar lymphadenopathy on chest x-ray. The patient’s parathyroid hormone (PTH) level was depressed in the presence of hypercalcemia. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level was elevated to 176 U/L (normal=12-68 U/L) and a screen for antinuclear antibody (ANA) was incidentally positive. Blood, bronchial, and skin cultures for fungi and bacteria were negative. Additionally, multiple acid-fast stains and bronchial cultures were negative for mycobacterial organisms. Laboratory data showed a microcytic anemia (Hg=10.5 g/dL, MCV=79 fL) with normal serum iron and ferritin levels. The total iron binding capacity (TIBC) was decreased and liver function tests were normal.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest confirmed marked hilar and mediastinal adenopathy. Additionally, there was diffuse ground glass opacity in the lower lungs bilaterally. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed multiple, mildly prominent pericaval and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, the largest measuring approximately 14 mm. The radiological findings were deemed consistent with a clinical diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis.

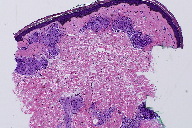

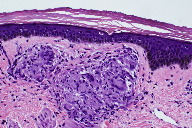

Skin biopsies were performed on the left shin and the right forearm. Histopathologic analysis of the left shin biopsy showed compact hyperorthokeratosis and patchy parakeratosis without epidermal spongiosis. Both the superficial and deep portions of the underlying dermis displayed non-necrotizing, well-formed granulomas with minimal lymphocytic infiltrates (Figures 2 and 3). Special cytochemical stains on both biopsies with Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Fite were negative for fungal and mycobacterial organisms, respectively. The pathologic findings of granulomatous dermatitis were considered to be consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Additionally, a transbronchial biopsy yielded noncaseating granulomas and a subcarinal fine needle aspiration (FNA) exhibited clusters of epithelioid histiocytes.

The diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis was made based upon the clinical, radiographic, and pathologic data. The patient was discharged home on 10 mg oral prednisone daily. She is being followed by the dermatology, rheumatology, pulmonology, and internal medicine services. At follow-up to 12 months, her cutaneous symptoms have mildly improved and her pulmonary function has not worsened. She continues to be maintained on 20 mg of oral prednisone.

Discussion

Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis is a rare cutaneous sign of systemic sarcoidosis. Only one previously described case did not eventually progress to multisystem involvement. Lesions have been described as large thin scales with adherent centers giving a “pasted on” appearance [4]. The first report of this condition was by Braverman in 1970 as an acquired ichthyosis preceding the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis. Cutaneous biopsy demonstrated noncaseating granulomas [5]. Since that time, there have been a total of 23 reported cases of so-called ichthyosiform sarcoidosis, including ours [4-20]. Ichthyosiform manifestations of sarcoidosis remain an excellent marker for systemic disease with 95 percent of reported cases demonstrating multisystem involvement [17].

The demographic composition of previous cases is similar to that of sarcoidosis in general. Sarcoidosis is seen most commonly in African-Americans (incidence of 35-80 per 100,000) followed by Northern Europeans (incidence of 15-20 per 100,000) with median age at onset in the 3rd to 4th decades. In all races there is a 10-30 percent increased risk for systemic sarcoidosis in women [21]. Ichthyosiform skin manifestations have a predilection for dark-skinned races. Of cases in which race was identified, 2 were East Indian and 15 were black, including our patient. There have been no reported cases in Caucasians. In cases in which age was reported, the median age of onset of ichthyosiform sarcoidosis was slightly younger among women (32 years, range 22-54) compared to men (48 years, range 21-68 years) [5, 7, 9-13, 16-19].

Including our patient, 4 previous cases have been described in which the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis occurred simultaneously with the diagnosis of cutaneous ichthyosis [5, 7, 11]. In 9 reported cases, the diagnosis of acquired ichthyosis preceded a diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis by a median of 3 months (n=11, range 2-48 months) [5-7, 9, 10, 12, 14, 17, 18]. Of cases that discussed the primary diagnosis of systemic disease, 15 of 17 patients (88%), including ours, had data that defined the onset of cutaneous ichthyosiform lesions at the time of or prior to diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis. Only 4 cases noted that the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis preceded any cutaneous ichthyosis; in these cases, systemic illness predated cutaneous manifestations by a median of 21 months (range 2 to 36 months) [8, 12, 13, 15].

Sarcoidosis remains, by nature, a disease with a poorly understood pathogenesis and epidemiology. It has been previously noted that both populations of West African ancestry and women have greater predisposition for the disorder. The most frequently identified genes associations involve human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles [20]. For instance, HLA-DRB1*0301/DQB1*0201 has been associated with good prognoses in patients with Lofgren syndrome [22]. According to the ACCESS study (A Case-Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis), African-Americans have a sibling recurrence-risk ratio of approximately 2.2 (CI 1.03 to 3.68) times higher than the disease risk amongst siblings in the general population. Further, patients were 5 times more likely to report an affected sibling or parent than in the general population [22].

The histopathology of ichthyosiform sarcoidosis shows the combined features of acquired ichthyosis and sarcoidosis. Biopsy usually demonstrates hyperkeratosis, thinning or absence of the stratum granulosum, and mild epidermal acanthosis. Additionally, the dermis will contain noncaseating granulomas of sarcoidosis [17]. The finding of granulomatous dermatitis is not specific for sarcoidosis and other etiologies should be eliminated, including infectious and autoimmune diseases, foreign body granulomas, neoplasms, immunodeficiency disorders, and drug eruptions [23].

Treatment modalities for cutaneous sarcoidosis are mixed because of the variable efficacy of standard therapies, associated toxicities, and presence of systemic symptoms. Standard therapy consists of topical corticosteroids, but can be advanced to intralesional and systemic steroids. Other therapeutic options for generalized cutaneous sarcoidosis include antimalarials, methotrexate, pentoxifylline, isotretinoin, leflunomide, thalidomide, infliximab, chlorambucil, melatonin, cyclosporine, allopurinol, and laser surgery [24]. Patients with ichthyosiform lesions of may require oral corticosteroid therapy [6, 10-13, 17].

Conclusion

Sarcoidosis is a multi-organ, systemic disease that may be diagnosed earlier, given characteristic dermatologic findings. Acquired ichthyosis presenting in a patient should prompt further exploration as this may be a sign of systemic disease. Further, patients carrying the combined diagnosis of sarcoidosis with acquired ichthyosis may progress rapidly, needing systemic therapy and involvement of a multi-disciplinary team.

References

1. Samtsov AV. “Cutaneous sarcoidosis.” Int J Dermatol 1992; 31:385-91. [PubMed]2. Hanno R, Needelman A, Eiferman RA, Callen JP. “Cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas and the development of systemic sarcoidosis.” Arch Dermatol 1981; 117:203-7. [PubMed]

3. Judson MA, Thompson BW, Rabin DL, et al. “The diagnostic pathway to sarcoidosis.” Chest 2003; 123:406-12. [PubMed]

4. Marchell, RM, Judson, MA. “Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis.” Clin Dermatol 2007; 25:295-302. [PubMed]

5. Braverman, IM. “Sarcoidosis.” Skin signs of systemic disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1970. p. 516-31.

6. Kelly AP. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis [letter].” Arch Dermatol 1978;114:1551-2.

7. Mountcastle EA, Lupton GP. “An ichthyosiform eruption of the legs: sarcoidosis.” Arch Dermatol 1989; 125:1415-20. [PubMed]

8. Matsuoka LY, LeVine M, Glasser S, Barsky S. “Ichthyosiform sarcoid.” Cutis 1980; 25:188-9. [PubMed]

9. Griffiths CEM, Leonard JN, Walker MM. “Acquired ichthyosis and sarcoidosis.” Clin Exp Dermatol 1986; 11:296-8. [PubMed]

10. Kauh YC, Goody HE, Luscombe HA. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis.” Arch Dermatol 1978; 114:100-1. [PubMed]

11. Mora R, Gullung WH. “Sarcoidosis: a case with unusual manifestations.” South Me J 1980; 73:1063-5. [PubMed]

12. Matarasso SL, Bruce S. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of a case.” Cutis 1991; 47:405-8. [PubMed]

13. Banse-Kupin L, Pelachyk JM. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of two cases and a review of the literature.” J Am Acad Dermatol 1987; 17:616-20. [PubMed]

14. Fred HL, Rapini RP, Jones SM. “A black man with simultaneous multisystem disease.” Houston Med 1990; 6:161-72.

15. Heng MCY, Chan C, Kloss SG. “Electron microscopic findings in ichthyosis secondary to sarcoidosis.” Australas J Dermatol 1986; 27:127-30. [PubMed]

16. Feind-Koopmans AG, Lucker GPH, van de Kerkhof PCM. “Acquired ichthyosiform erythroderma and sarcoidosis.” J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35:826-8. [PubMed]

17. Minus HR, Grimes PE. “Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis in blacks.” Cutis 1983; 32:361-63,372. [PubMed]

18. Cather J, Cohen PR. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis.” J Am Acad Dermatol 1999; 40:862-5. [PubMed]

19. Rosenberg, B. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis.” Dermatol Online J 2005; 11:15. [PubMed]

20. Gangopadhyay, AK. “Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis.” Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2001; 67:91-2. [PubMed]

21. Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi, MC. “Epidemiology of Sarcoidosis.” Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 28:22-35. [PubMed]

22. Iannuzzi, MC. “Genetics of Sarcoidosis.” Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 28:15-21.

23. Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol 2007; 25:276-287.

24. Badgwell C, Rosen T. Cutaneous sarcoidosis therapy updated. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 56: 69-83.

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal