Oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Underdiagnosed oral precursor lesion that requires retrospective clinicopathological correlation

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D32tp4f7kxMain Content

Oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Underdiagnosed oral precursor lesion that requires retrospective clinicopathological

correlation

Ozgur Mete1, Yaren Keskin2, Gunter Hafiz3, Kivanc Bektas Kayhan2, Meral Unur2

Dermatology Online Journal 16 (5): 6

1. Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pathology. ozgurmete77@gmail.com2. Istanbul University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Oral Medicine and Surgery

3. Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Department of ENT Surgery

Abstract

We present herein a case of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (OPVL) and discuss this relatively rare entity in light of current information. A 59-year-old woman, non-smoker, presented with a verrucous plaque at the left ventral and dorsal surfaces of the tongue that she had first noticed in 2001. At that time, the plaque was excised and revealed benign hyperkeratosis. The growth recurred and was again excised. Histologically it was characterized by a verrucous epithelial hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and mild epithelial dysplasia. Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA typing for low, intermediate, and high-risk groups was also performed and no etiological link between HPV and this lesion was found. The overall progressive clinical and histopathological findings were considered diagnostic for OPVL. Because of the lack of specific histological features and the progressive proliferative characteristic of OPVL, the recognition of this underdiagnosed entity is critical because apparently innocent looking oral verrucous lesions, irrespective of the presence of dysplasia, may progress into carcinoma. On the other hand, it is of interest that the early phase of these lesions usually exhibits an interface lymphocytic infiltrate that may mimic an oral lichenoid stomatitis such as lichen planus. It is therefore important to follow-up closely any patient with oral leukoplakia and those diagnosed with non-specific lichenoid stomatitis.

Introduction

Oral leukoplakia (OL) is characterized by adherent white plaques or patches on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, including the tongue [1, 2]. The clinical appearance is highly variable and OL is not a specific disease entity, but is a diagnosis of exclusion [1, 2]. It is therefore not a histologically appropriate diagnostic term for any one pathological entity. However, epithelial dysplasia is a microscopically defined change that may occur in clinically identifiable lesions including erythroplakia, leukoplakia, and erythroleukoplakia [2, 3, 4]. Oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (OPVL) is a rare clinicopathological entity, but is a distinctive high-risk clinical form of oral precursor lesion [4, 5, 6, 7]. Women are more commonly afflicted (ratio, 4:1) and the mean age at the time of diagnosis is slightly over 60 years [4, 5, 6, 7]. The buccal mucosa and tongue are the most common sites associated with OPVL; palatinal mucosa, alveolar mucosa, gingiva, floor of mouth, and lip show a lower incidence [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Typically, multiple oral sites can be also affected [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. It is characterized by high recurrence rate and histological progression to typical squamous cell carcinoma or verrucous carcinoma [4-9]. Because of the lack of specific histological criteria, the diagnosis of OPVL is based on combined clinical and histopathologic evidence of progression [4]. We discuss the clinical, histopathological, pathogenic, and cellular characteristics of this rare entity in light of information from the literature.

Case report

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

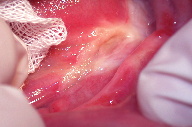

| Figure 1. Whitish-pink elevated irregular plaques that exhibit verrucous projections Figure 2. Skin graft is placed at the site of excision. | |

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

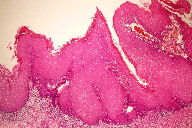

| Figure 3. Sections from areas of plaque revealed irregular epithelial hyperplasia, variable hyperkeratosis, mild dysplastic change, and mild subepithelial lymphocytic infiltrate (H&E, x20) |

A 59-year-old non-smoking, woman presented with a slowly progressive plaque at the left ventral and dorsal surfaces of the tongue. It had first been noticed in 2001 as a 0.5 cm flat whitish-grey homogenous lesion. At that time, the lesion was excised outside of our hospital and was diagnosed as benign hyperkeratosis; further treatment was not planned. Her past medical history, including her family history, was unremarkable. There was no history of frank trauma to the relevant side of the tongue. When she was referred to our hospital in 2008, the lesion was about 6 cm in size, whitish-pink, with irregular verrucous areas (Figure 1). In addition to this, poor oral hygiene and severe periodontitis was noted. An incisional biopsy was performed and histopathological examination revealed areas of acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis. Subsequently, the patient underwent surgical excision followed by skin graft placement. The surgical specimen revealed verrucous epithelial hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, and mild epithelial dysplasia suggestive of OPVL (Figures 2-5). Human papillomavirus DNA for low, intermediate, and high-risk groups was not detected in the specimen using two different kits (digene HPV HC2 DNA test and DNA chip-Papillocheck HPV Screening). The overall clinical and histopathological findings were considered diagnostic for OPVL. The postoperative course has been satisfactory and the patient is still under periodic follow-up once every three months.

Discussion

Precancerous lesions of the squamous epithelium of oral mucosa are clinically characterized mainly by leukoplakia, erythroplakia and mixed leukoerythroplakia [1, 2, 3, 4]. OPVL is a very high-risk premalignant growth with a high mortality rate [4-10]. The presented case highlights the typical slow-growing, progressive, and persistent clinical course of this rare entity. As presented in our case, the initial finding can be a solitary, flat homogeneous whitish-grey lesion that tends to recur and proliferate, often over a protracted period of time, to result in a diffuse and widespread exophytic, verrucous intraoral plaque that may be also erythematous and erosive [5, 6, 7]. Although the verrucous nature is classically observed in the late progressive stage of OPVL, this can be rarely present at the time of the initial lesion [5, 6, 7].

Although there is usually a time lag between the appearances of new tumors in the same patient, OPVL might have an infectious etiology, possibly a viral infection. However, the etiology of OPVL remains still unclear [4, 5, 6, 7]. To date, several studies in relatively small cohorts have investigated the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in OPVL. Between 0 percent and 89 percent of OPVL are reported to be HPV positive, especially for HPV types 16 and 18 [10-13]. On the other hand, one of the largest studies evaluating HPV in verrucous and conventional leukoplakias reported HPV DNA rates of 24.1 percent and 25.5 percent, respectively [13]. Apparently, there is no unequivocal pathogenetic link between HPV and OPVL. In this context, OPVL has been reported also in association with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). However, the method used in that study cannot distinguish the possible presence of EBV in epithelium from EBV in infiltrating B-lymphocytes [14].

Kresty et al. reported for the first time, that there is a notable difference in the mode and incidence of INK4a/ARF inactivation events in OPVL compared with non-OPVL high-risk premalignant lesions. The authors hypothesized that significant rates of concomitant alterations in the INK4a/ARF locus, as well as increases in p14-ARF and p16-INK4a homozygous deletion rates, contribute to the extremely aggressive nature of OPVL [10]. In addition to that, transforming growth factor-alpha expression (TGF-α), up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), DNA ploidy, p53 mutation, and tumor suppressor loci for loss of heterozygosity (LOH) have been studied in OPVL. However, none of these studies have produced a clear insight in the etiopathogenesis of OPVL [6, 7, 15-20].

Histopathologic features of OPVL vary from entirely benign hyperkeratosis to frankly malignant features, with areas of squamous cell carcinoma [4, 6, 7]. Proposed staging for OPVL includes four clinicopathological phases: clinically flat leukoplakia without dysplasia, verrucous hyperplasia with or without dysplasia, verrucous carcinoma, and conventional or papillary squamous cell carcinoma [4, 6, 7]. Papillomatosis per se is not a sign of dysplasia, but dysplasia is seen in biopsies from patients with OPVL. For some authors, verrucous hyperplasia represents an irreversible precursor stage of verrucous carcinoma. It is of interest that the early phase of these lesions usually exhibits an interface lymphocytic infiltrate that may have a pronounced lichenoid pattern characterized by basal vacuolar degeneration containing apoptotic cells and eosinophilic bodies, similar to types of oral lichenoid stomatitis such as lichen planus [6]. Enhanced acanthosis and basilar hyperplasia with or without dysplasia may be identified. However, one histological pitfall for OPVL, when present, is an abrupt transition from hyperparakeratosis to hyperorthokeratosis, associated with a corrugated or verruciform surface [6].

It is known that approximately 80 percent of OPVLs progress to oral carcinoma over a period of time in spite of a variety of interventions [6]. This feature contrasts with conventional OL in which approximately 5-10 percent will transform into a carcinoma [2, 4, 6]. Clearly, OPVL is resistant to the presently available treatment modalities, including cold knife surgery, CO2 laser surgery, chemotherapy, and irradiation [6, 7]. Therefore, total excision with free surgical margins is critical combined with a lifelong follow-up.

Conclusion

Because of the lack of specific histological features and the progressive proliferative characteristics of OPVL, this entity is histologically underdiagnosed. In fact, in most of the cases, OPVL is a retrospective clinicopathological diagnosis for OL that encompasses a spectrum of clinical and histological stages prone to exhibit recurrence. At times it may demonstrate clinical and microscopic features of malignancy. Dentists, dermatologists, ENT specialists, or physicians in primary care may confront asymptomatic initial and progressive lesions of OPVL in the routine clinical examination. The recognition of this underdiagnosed entity and total excision of this lesion is critical. Apparently innocent looking oral verrucous lesions, irrespective of the presence of dysplasia, may progress into carcinoma. It is therefore important to follow-up closely any patient with recurrent OL and non-specific lichenoid stomatitis.

References

1. Silverman S Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563–8. [PubMed]2. Scully C. Oral Leukoplakia. [eMedicine web site]. October 2008. Accessed October 30, 2009.

3. Eversole LR. Dysplasia of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract Squamous Epithelium. Head and Neck Pathol. 2009;3:63–8. [DOI: 10.1007/s12105-009-0103-8, ISSN: 1936-055X (Print), 1936-0568 (Online)]

4. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (Eds): World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press. Lyon 2005.

5. Hansen LS, Olson JA, Silverman S Jr. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:285-98. [PubMed]

6. Morton TH, Cabay RJ, Epstein JB. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its progression to oral carcinoma: report of three cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:315-8. [PubMed]

7. van der Waal I, Reichart PA. Oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia revisited. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:719-21. [PubMed]

8. Fettig A, Pogrel MA, Silverman S Jr, Bramanti TE, Da Costa M, Regezi JA. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:723-30. [PubMed]

9. Navarro CM, Sposto MR, Sgavioli-Massucato EM, Onofre MA. Transformation of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia to oral carcinoma: a ten years follow-up. Med Oral. 2004;9:229-33. [PubMed]

10. Kresty LA, Mallery SR, Knobloch TJ, Li J, Lloyd M, Casto BC, Weghorst CM. Frequent alterations of p16INK4a and p14ARF in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3179-87. [PubMed]

11. Palefsky JM, Silverman S,Jr., Abdel-Salaam M, Daniels TE, Green-span JS. Association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and infection with human papillomavirus type 16. J Oral Pathol Med.1995;24:193–7. [PubMed]

12. Bagan JV, Jimenez Y, Murillo J, Gavaldá C, Poveda R, Scully C, Alberola TM, Torres-Puente M, Pérez-Alonso M. Lack of association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and human papillomavirus infection. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:46-9. [PubMed]

13. Campisi G, Giovannelli L, Ammatuna P, Capra G, Colella G, Di Liberto C, Gandolfo S, Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Serpico R, D'Angelo M. Proliferative verrucous vs conventional leukoplakia: no significantly increased risk of HPV infection. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:835-40. [PubMed]

14. Bagan JV, Jiménez Y, Murillo J, Poveda R, Díaz JM, Gavaldá C, Margaix M, Scully C, Alberola TM, Torres Puente M, Pérez Alonso M. Epstein-Barr virus in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma: A preliminary study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E110-3. [PubMed]

15. Kannan R, Bijur GN, Mallery SR, Beck FM, Sabourin CL, Jewell SD, Schuller DE, Stoner GD. Transforming growth factor-alpha overexpression in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:69-74. [PubMed]

16. Mohan S, Epstein JB. Carcinogenesis and cyclooxygenase: the potential role of COX-2 inhibition in upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oral Oncol. 2003; 39:537–46. [PubMed]

17. Sudbø J, Ristimäki A, Sondresen JE, Kildal W, Boysen M, Koppang HS, Reith A, Risberg B, Nesland JM, Bryne M. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in high-risk premalignant oral lesions. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:497-505. [PubMed]

18. Klanrit P, Sperandio M, Brown AL, Shirlaw PJ, Challacombe SJ, Morgan PR, Odell EW. DNA ploidy in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:310-6. [PubMed]

19. Gopalakrishnan R, Weghorst CM, Lehman TA, Calvert RJ, Bijur G, Sabourin CL, Mallery SR, Schuller DE, Stoner GD. Mutated and wild-type p53 expression and HPV integration in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:471-7. [PubMed]

20. Epstein JB, Zhang L, Poh C, Nakamura H, Berean K, Rosin M. Increased allelic loss in toluidine blue-positive oral premalignant lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:45–50. [PubMed]

© 2010 Dermatology Online Journal