Blueberry muffin baby: A pictoral differential diagnosis

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D353q852ncMain Content

Blueberry muffin baby: A pictoral differential diagnosis

Vandana Mehta, C Balachandran, Vrushali Lonikar

Dermatology Online Journal 14 (2): 8

Department of Skin and STD, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, India. vandanamht@yahoo.comThe term blueberry muffin baby was initially coined by pediatricians to describe cutaneous manifestations observed in newborns infected with rubella during the American epidemic of the 1960s [1]. These children had generalized hemorrhagic purpuric eruptions that on histopathology showed dermal erythropoiesis. Since then, congenital infections comprising the TORCH syndrome (toxoplasmosis, other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes) and hematologic dyscrasias have classically been associated with blueberry muffin-like lesions.

Etiopathogenesis

Hematopoiesis in the newborn dermis was first documented in 1925 by Dietrich and since then it has nearly always has been associated with some pathologic process beginning in-utero [2]. Although the exact cause of prolonged dermal erythropoiesis is unknown, during normal embryologic development extramedullary hematopoiesis occurs in a number of organs, including the dermis; this activity persists until the fifth month of gestation. Normally, leukocytes phagocytize the erythroblastic elements by 34-38 weeks gestation. The presence of blueberry muffin lesions at birth represents postnatal expression of this normal fetal extramedullary hematopoiesis [3].

Clinical Features

|  |

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Magenta coloured papulonodular lesions suggestive of dermal hematopoiesis Figure 2. Close-up of the lesions | |

Characteristically, the blueberry muffin morphology presents as non-blanching, blue-red macules or firm, dome-shaped papules (2-8 mm in diameter). The eruption is often generalized but favors the trunk, head, and neck (Figs. 1 & 2). The macules and papules are present at birth and generally begin to resolve soon after to leave light brown macules. Clearing usually occurs by 3-6 weeks after birth. Known conditions that cause extramedullary hematopoiesis include intrauterine infections and hematologic dyscrasias. However, we agree that the colorful and descriptive term, blueberry muffin baby should be expanded beyond infectious and reactive hematologic causes [4] to include several neoplastic and vascular processes as outlined in Table 1.

|  |

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

|---|---|

| Figure 3. Purpuric lesions on the trunk in a case of congenital CMV infection Figure 4. Rash in a child with congenital CMV infection | |

|

| Figure 5 |

|---|

| Figure 5. Purpuric lesions on the leg in a child with congenital CMV |

Among the TORCH group of infections, Cytomegalovirus(CMV) is the most common viral agent; the incidence of congenital CMV infection is 0.3 percent to 2.2 percent. A related cutaneous eruption is present in less than 5 percent of cases. Rubella and CMV are the only TORCH viruses that have been documented by skin biopsies to cause dermal erythropoiesis. The affected neonates are premature and small for gestational age. Clinically, deafness, chorioretinitis, and psychomotor retardation are often associated. On physical and laboratory examination, hepatosplenomegaly, direct hyperbilirubinemia, high anti-cytomegalovirus specific IgM titer, positive cytomegalovirus urine culture, and thrombocytopenia are commonly found [5] (Figs. 3, 4 & 5).

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (ABO or Rh incompatibility) and hereditary spherocytosis are also known causes for a blueberry muffin appearance. The presence of generalized edema of varying degrees, Coombs' positive hemolytic anemia, and laboratory documentation of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia distinguish them from congenital infections and malignancies [6].

|  |

| Figure 6 | Figure 7 |

|---|---|

| Figure 6. Racoon eyes in neuroblastoma with CT scan showing the tumor Figure 7. Bluish nodules in a child with Neuroblastoma | |

The twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome can occur in any monochorionic twin pregnancy when some placental cotyledons receive blood from one fetus (donor) and drain it to the other fetus (recipient). Usually the syndrome is benign, but when severe, the donor twin exhibits low birth weight, anemia, and high output cardiac failure. The recipient is plethoric with a hemoglobin concentration of at least 5gm/dl higher than that of the donor [7].

Neuroblastoma is the most common malignancy of infants and children with most cases presenting during the first five years of life. The cutaneous eruption resembles a blueberry muffin appearance, but demonstrates a characteristic blanch response on palpation that leaves a surrounding rim of erythema. Ocular signs such as "racoon eyes" or periorbital ecchymosis and heterochromia irides may be present. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry along with increased urinary excretion of catecholamines confirm the diagnosis [8] (Figs. 6 & 7).

|  |

| Figure 8 | Figure 9 |

|---|---|

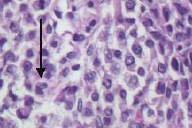

| Figure 8. Purpuric lesions resembling a blue berry muffin in a leukemic child Figure 9. Histopathology showing abnormal lymphocytes in the dermis | |

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the second most common malignancy of infancy and represents 3 percent of all childhood leukemias. Infiltration of the skin with leukemic cells (leukemia cutis), usually occurs concomitantly with the development of systemic leukemia, but may precede the latter by weeks to months and heralds a poor prognosis. Chloroma has been the term historically used to describe the myelogenous infiltrates in the skin of patients with AML. The green color is attributed to the presence of myeloperoxidase. Other features such as pallor, lethargy, leukocytosis, hepatosplenolegaly, fever, and CNS involvement in a neonate further suggest the diagnosis of congenital leukemia [9, 10] (Figs. 8 & 9).

|  |

| Figure 10 | Figure 11 |

|---|---|

| Figure 10. Papules with central ulceration in LCH Figure 11. Purpuric lesions on the hand in LCH | |

|

| Figure 12 |

|---|

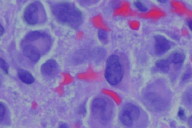

| Figure 12. High power photomicrograph showing large moonuclear cells with reniform nucleus in the epidermis with eosinophilic cytoplasm in LCH |

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) represents clonal proliferation of the Langerhans cell and is of enigmatic etiology. This condition may affect single or multiple organ systems. Skin involvement in LCH has been reported to occur in more than half of the patients. The characteristic cutaneous findings are small 2-10mm yellow- brown papules or nodules that may be pseudovesicular and often develop central ulceration. Although not often confused with blueberry muffin infants, another characteristic presentation of LCH that should be acknowledged is the seborrheic dermatitis-like presentation with multiple petechiae. The characteristic histopathology shows a dense dermal infiltrate of histiocytes with kidney shaped nuclei, typical immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy that reveals Birbeck's granules [11] (Figs. 10, 11, 12).

|  |

| Figure 13 | Figure 14 |

|---|---|

| Figure 13. Multiple hemangiomas on the face Figure 14. Close-up of hemangioma | |

|

| Figure 15 |

|---|

| Figure 15. Glomangioma |

Apart from the conditions mentioned above many congenital vascular lesions may impart a blueberry muffin appearance. However, relatively few of these are multifocal in nature. Multiple hemangiomas of infancy, multifocal lymphangioendotheliomatosis, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome and multiple glomangiomas are four such conditions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an infant with a blueberry muffin appearance [4] (Figs. 13, 14, 15, 16, 17).

|  |

| Figure 16 | Figure 17 |

|---|---|

| Figure 16. Glomovenous malformation on the leg Figure 17. Multiple glomus tumors on the soles | |

Neonatal lupus erythematosus commonly occurs in babies due to transplacental passage of maternal autoantibodies to ribonucleoproteins (Ro-SSA,La-SSB). Certain presentations of this condition have also been included as one of the differential diagnoses for the blueberry muffin baby (Fig 18).

|

| Figure 18 |

|---|

| Figure 18. Erythematous sclay plaques in a spectacle frame like distribution suggestive of Neonatal lupus erythematosus |

Diagnosis and investigations

The blueberry muffin rash in a neonate signifies a potentially live-threatening condition with severe sequelae. The primary laboratory investigations that are useful in establishing a diagnosis are outlined in Table 2.

Conclusion

The blueberry muffin baby has been associated historically with congenital viral infections and hematologic dyscrasias. However, the differential diagnosis of neonatal violaceous skin lesions should be expanded to include several neoplastic and vascular disorders as well. Such lesions in a neonate may have serious systemic implications and require diagnosis by means of skin biopsy and laboratory evaluation.

References

1. Barnett HL, Einhorn AH. Paediatrics. 14th ed. New York: Appleton- Century- Crofts,1968: 742.2. Dietrich H. Studien uber extramedullare Blutbildung bei Chirugichen Erkrankungen. Arch Klin Chirug 1925;134:166

3. Argyle JC, Zone JJ. Dermal erythropoiesis in a neonate. Arch Dermatol 1981;117:492-4. PubMed

4. Holland KE, Galbraith SS, Drolet BA. Neonatal violaceous skin lesions: expanding the differential of the "blueberry muffin baby". Adv Dermatol 2005;21:153-92. PubMed

5. Fine JD, Arndt KA. The TORCH syndrome: a clinical review. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;12:697-706. PubMed

6. Hebert AA, Esterly NB, Gerdner TH. Dermal erythropoiesis in Rh haemolytic disease of the newborn. J Pediatr 1985;107:799-801. PubMed

7. Schwartz JL, Maniscalco WM, Lane AT, Currano WJ. Twin transfusion syndrome causing cutaneous erythropoiesis. Pediatrics 1984;74:527-9. PubMed

8. Mopett J, Haddadin I, Foot ABM. Neonatal neuroblastoma. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999;81:134-337.

9. Dasgupta MK, Nayak K. Congenital leukaemia cutis. Indian Pediatr 2001;38:1315. PubMed

10. Sauter C, Jacky E. Chloroma in acute myelogenous leukaemia. N Eng J Med 1998;338:969. PubMed

11. Schaffer MP, Walling HW, Stone MS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as a blueberry muffin baby. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:S143-6. PubMed

© 2008 Dermatology Online Journal