Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis.

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D330x073xrMain Content

Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption in a case of short bowel syndrome following jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis.

N Suchithra, P Sreejith, Joseph M Pappachan, Josemon George, P K Rajakumari, George Cheriyan

Dermatology Online Journal 13 (3): 20

Department of Medicine, Kottayam Medical College, South IndiaAbstract

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of zinc deficiency. Zinc is an essential trace element in human metabolism and acquired zinc deficiency may manifest with skin eruptions simulating acrodermatitis enteropathica. We report an unusual case of acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption due to deficiency of zinc and other nutritional factors in a patient who has undergone extensive small bowel resection and jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis for mesenteric ischemia.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of zinc deficiency [1] and is characterized by a triad of dermatitis, diarrhea, and alopecia [1, 2]. It is attributed to the inability to absorb zinc from the gastrointestinal tract [2]. The genetic defect has been mapped to chromosome 8 and the defective gene encodes the zinc transporter [1].

Acquired zinc deficiency can occur with inadequate supply, malabsorption, and low zinc stores. Short bowel syndrome [3], Crohn's disease [4], intestinal parasitic infestations [5], food allergy [6], eating disorders [7], and a rare inborn error of metabolism known as non-ketotic hyperglycemia [2] are some of the other causes of acquired zinc deficiency. We report a case of acquired zinc deficiency that presented with acrodermatitis enteropathica-like skin eruption following extensive bowel resection and jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis in a patient with superior mesenteric artery thrombosis.

Clinical synopsis

A 19-year old female was admitted for evaluation of hyperpigmentation of the lips and pruritic skin lesions over the extremities and the low back for 2 weeks. She also had episodic diarrhea without the passage of blood and mucous. She had undergone resection of the major portion small bowel and the right half of the colon 6 months earlier for thrombosis of the superior mesenteric artery, while she was in her eighth month of gestation. A jejuno-transverse colon anastomosis also had been performed at that time.

Evaluation for thrombophilic states as a cause for superior mesenteric artery thrombosis did not reveal any abnormality. After a period of treatment with total parenteral nutrition, the patient was slowly switched over to enteral feeding and was discharged from the hospital with proper nutritional counseling. She had defaulted from follow up and presented with the skin lesions later. Her menstrual cycles were normal.

|  |

| Figure 1A | Figure 1B |

|---|---|

| Figure 1A. Psoriasiform dermatitis of the hands. 1B. Disappearance of the skin lesions after one month of treatment with zinc. | |

|  |

| Figure 2A | Figure 2B |

|---|---|

| Figure 2A. Dermatitis of the legs. 2B. Disappearance of the rash after zinc treatment. | |

Physical examination revealed lip hyperpigmentation, cheilitis and stomatitis. She was emaciated. Hyperpigmented and scaly skin lesions were noticed on the dorsum of the hands (Fig. 1A), the lower extremities (Fig. 2A) and the sacral area. The hairs were thin and she reported that she had significant loss of hair in the past few months. The remainder of the systemic examination was normal.

The laboratory investigations revealed: hemoglobin 13.5 gm/dL, total leukocyte count 10500/cmm, polymorphs 64 percent lymphocytes 36 percent, platelet count 180 x103/cmm and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 2 mm/hour. Alkaline phosphatase level was 28 U/L (normal 30-120 U/L). Blood sugar, urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function tests and electrolytes were in the reference range and the urine and stool analysis did not show any abnormality. The plasma zinc level was 62 micrograms/dL (normal laboratory reference range was reported to be 72 to 115 micrograms/dL).

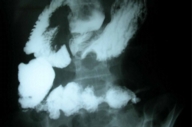

A barium-meal follow through examination revealed normally functioning jejuno-colic anastomosis (Fig. 3). Gastroduodenoscopy and biopsy of the 2nd part of duodenum did not reveal any abnormality.

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

| Figure 3. Barium-meal follow through examination showing normally functioning jejuno-colic anastomosis. |

The diagnosis acrodermatitis enteropathica associated with acquired zinc deficiency was made. The patient was treated with oral supplementation of elemental zinc 50 mg daily. Thorough nutritional counseling was given and a diet rich in essential fatty acids and other macro and micronutrients were prescribed because of the high likelihood of coexistent deficiencies from the patient's short bowel syndrome (SBS). She showed marked improvement within the first week of therapy and all the skin eruptions disappeared in a period of one month (Figs. 1B and 2B).

Discussion

Zinc is an essential trace element that is an integral component of many metallo-enzymes in the body. Zinc stabilizes the membranous structures of the cells and protects their integrity by reducing the formation of free radicals and by the prevention of lipid peroxidation. Zinc also has a fundamental role in gene replication, activation, and repression [8]. It is involved in the synthesis and the stabilization of protein, DNA, and RNA. It plays structural role in ribosomes and their membranes. It is necessary for the binding of steroid hormone receptors and several other transcription factors for DNA. Zinc is also required for normal spermatogenesis, embryogenesis and fetal growth.

Zinc is known to play a central role in the immune system, and zinc-deficient persons experience increased susceptibility to a variety of pathogens [8]. Host resistance to infections is altered by zinc deficiency. Treatment with zinc was found to lower the rates of child morbidity and mortality from diarrheal diseases [9]. Recent epidemiological and clinical evidence has shown that in most developing countries deficiencies of specific micronutrients are partly responsible for the severity of infectious disease morbidity and mortality in malnourished children. Zinc supplementation may reduce the duration of malaria, and the severity of diarrhea and respiratory infections. It may improve immunocompetence in susceptible children.

Clinical zinc deficiency in humans was first described in 1961 when the consumption of diets with low zinc bio-availability attributed to high phytic acid content that was associated with adolescent nutritional-dwarfism in the Middle East. Zinc deficiency has been recognized as an important public health issue in developing countries.

Hereditary zinc deficiency occurs as an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by periorificial and acral dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea and is termed acrodermatitis enteropathica [1, 2]. The disorder is thought to result from an abnormality in the zinc transporter; the genetic defect has been mapped recently on chromosome 8 [1].

Zinc absorption occurs mainly in the jejunum; acquired deficiency of zinc occurs in a large number of disorders affecting the gastrointestinal tract [3, 4, 5, 6]. Various dietary factors reduce zinc absorption (high phytate diet). In addition, several problems contribute to poor zinc intake or excessive loss such as alcoholism, eating disorders[7], total parenteral nutrition, trauma (burns and surgery), malignancy, renal disease, pregnancy, and lactation.

The manifestations of both the hereditary and the acquired forms of zinc deficiency are similar. The dermatitis presents as dry, scaly, erythematous, plaques on the face, scalp, extremities and anogenital areas [1, 2]. Chronic lesions may be more psoriasiform. Cheilitis and angular stomatitis are commonly seen. Nail dystrophy may be present. Generalized alopecia is characteristic and gradually worsens with time. Diarrhea is the most variable manifestation and it may be intermittent or totally absent. Other manifestations are growth failure, dwarfism, delayed puberty, hypogonadism, mental and emotional disturbances, photophobia, frequent infections, and delayed healing of wounds [1].

The diagnosis is based on the clinical picture and estimation of plasma zinc concentration. Most patients have plasma levels below 50 micrograms/dL. Circulating and tissue levels of zinc do not necessarily reflect the zinc status of the body. Hair levels may also be measured. Low levels of serum alkaline phosphatase may support a diagnosis of zinc deficiency. A skin or intestinal mucosal biopsy also may aid the diagnosis. Improvement of the dermatitis with zinc supplementation is another good indicator of deficiency.

The management of a patient with the clinical picture suggestive of acquired zinc deficiency is by zinc supplementation at a daily dosage of 30-55 mg of elemental zinc (1-2 mg per kg per day). Response to treatment may take days to weeks, depending on the degree of zinc depletion. The patient should be maintained on lifelong oral zinc supplementation after the diagnosis unless the underlying problem is remediable.

Reduction of absorptive area from resection of a large portion of bowel including the major portion of jejunum has resulted in zinc and probably other deficiencies in this patient. Short bowel syndrome following bowel resection is an important cause of malabsorption and deficiency of multiple nutrients [3, 10, 11]. Thorough nutritional management is the key factor in achieving an optimal outcome in SBS [3, 11]. Following bowel resection, the remaining bowel undergoes a process called adaptation, which may replace the lost intestinal function and the administration of various factors stimulating intestinal adaptation is the cornerstone of management. Surgical methods may be required for treatment including intestinal transplantation, as a last resort for the treatment of end-stage intestinal failure [1].

Deficiencies of branched-chain amino acids and essential fatty acids also may mimic a clinical picture of acrodermatitis enteropathica [12, 13, 14]. Patients with SBS may develop these deficiencies as well and nutritional supplementation of these factors also should be an integral part of management of patients with SBS. The low levels of zinc and alkaline phosphatase in the patient described suggests that our patient's dermatitis was related to zinc deficiency even though other nutritional factors also could have contributed to the severe clinical picture.

References

1. Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, Draznin M, Michael DJ, Ruben B, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Jan;56(1):116-24. PubMed2. Samady JA, Schwartz RA, Shih LY, Piela Z, Lambert WC, Janniger CK. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption in an infant with nonketotic hyperglycinemia. J Dermatol. 2000 Sep;27(9):604-8. PubMed

3. Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian CM. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002 Mar;34(3):207-20. PubMed

4. Griffin IJ, Kim SC, Hicks PD, Liang LK, Abrams SA. Zinc metabolism in adolescents with Crohn's disease. Pediatr Res. 2004 Aug;56(2):235-9. PubMed

5. Olivares JL, Fernandez R, Fleta J, Rodriguez G, Clavel A. Serum mineral levels in children with intestinal parasitic infection. Dig Dis. 2003;21(3):258-61. PubMed

6. Martin DP, Tangsinmankong N, Sleasman JW, Day-Good NK, Wongchantara DR. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption and food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005 Mar;94(3):398-401. PubMed

7. Strumia R. Dermatologic signs in patients with eating disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):165-73. PubMed

8. Shankar AH, Prasad AS. Zinc and immune function: the biological basis of altered resistance to infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Aug;68(2 Suppl):447S-463S. PubMed

9. Baqui AH, Black RE, El Arifeen S, Yunus M, Chakraborty J, Ahmed S, et al. Effect of zinc supplementation started during diarrhoea on morbidity and mortality in Bangladeshi children: community randomised trial. BMJ. 2002 Nov 9;325(7372):1059. PubMed

10. Vanderhoof JA, Langnas AN. Short-bowel syndrome in children and adults. Gastroenterology. 1997 Nov;113(5):1767-78. PubMed

11. Misiakos EP, Macheras A, Kapetanakis T, Liakakos T. Short bowel syndrome: current medical and surgical trends. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan;41(1):5-18. PubMed

12. Goskowicz M, Eichenfield LF. Cutaneous findings of nutritional deficiencies in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1993 Aug;5(4):441-5. PubMed

13. Kim YJ, Kim MY, Kim HO, Lee MD, Park YM. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruption associated with combined nutritional deficiency. J Korean Med Sci. 2005 Oct;20(5):908-11. PubMed

14. Templier I, Reymond JL, Nguyen MA, Boujet C, Lantuejoul S, Beani JC, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like syndrome secondary to branched-chain amino acid deficiency during treatment of maple syrup urine disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006 Apr;133(4):375-9. [French.] PubMed

© 2007 Dermatology Online Journal