Nasal septum perforation as the presenting sign of lupus erythematosus

Published Web Location

https://doi.org/10.5070/D38n61708jMain Content

Nasal septum perforation as the presenting sign of lupus erythematosus

R Mascarenhas, O Tellechea, H Oliveira, JP Reis, M Cordeiro , J Migueis

Dermatology Online Journal 11 (2): 12

Departments of Dermatology and Otorhinolaringology, Coimbra University Hospital, Coimbra, Portugal. dermopat@huc.min-saude.pt

Abstract

Nasal septum perforation is an uncommon and not well known feature of lupus erythematosus (LE). In general, it occurs during exacerbations and in a context of systemic vasculitis. Very rarely it can be a presenting sign, accompanying more usual manifestations of LE. We report the case of a 30-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of painful, slowly progressive nasal septum perforation. Laboratory study disclosed positive antinuclear antibodies, circulating immune complexes, hypocomplementemia, nuclear epidermal deposition of IgG in normal skin and transitory positive antiphospholipid antibodies. Symmetric peripheral joint arthritis, photosensitivity and diffuse alopecia subsequently developed. This case seems unique in that the nasal septum perforation occurred as an isolated presenting sign; it emphasizes the value of this feature in the diagnosis of LE.

Introduction

Oral ulcers, defined as oral or nasopharyngeal ulceration, is one of the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for lupus erythematosus (LE) [1, 2]. Although a recognized feature of LE, nasal septum perforation is uncommonly reported in this condition and rarely constitutes the presenting manifestation [3-11].

We report a case of LE where nasal septum perforation preceded the diagnosis and constituted the sole clinical feature during a period of two years.

Clinical synopsis

In May 2002 we observed a 30-year-old female with a slowly progressive nasal septum perforation first noticed 2 years before and heralded by minor epistaxis. A nasal septum mucosa biopsy performed 6 months before in another hospital disclosed a mild lymphomononuclear cell infiltrate of the corium and irregular acanthosis of the epithelium. Previous laboratory blood and urine tests performed in the same hospital disclosed no alterations except for the presence of antiphospholipid IgM antibodies.

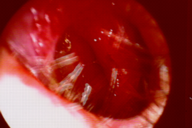

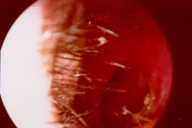

Examination showed an oval defect of the antero-inferior cartilaginous nasal septum with 2 cm of greater diameter (Fig. 1,2). The surrounding margin was erythematous, edematous, and tender (Fig. 1,2). The remaining ENT examination was normal. No other changes, including cutaneous, were observed. Besides tenderness, she complained of episodic epistaxis, and spontaneous, persistent pain.

|

|

| Figure 1 | Figure 2 |

|---|---|

| Fig. 1 Ð Nasal septum perforation on rhinoscopy (right). | |

| Fig. 2 Ð Nasal septum perforation on rhinoscopy (left) | |

Personal and familial antecedents were irrelevant. There was no history of previous local trauma, surgery, application of topical agents, or environmental exposure to metals. She did not smoke or take any medication or drugs.

Histological examination of a biopsy of nasal septum at the margin of the perforation showed a scarce interstitial and perivascular infiltrate of CD3 positive lymphocytes in the corium. There were no vasculopathy, vasculitis or granuloma formation. PAS and Fite-Faraco stains were negative.

|

| Figure 3 |

|---|

| Fig. 3 Ð Intranuclear epidermal deposition of IgG at direct immunofluorescence of normal skin of deltoid region |

Laboratory investigation disclosed positive (++++) antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), with positive Ro/SS-A, elevation of circulating immune complexes (6.66 µg/ml; N < 4,06µg/ml), hypocomplementemia (C4: 0,10 g/L; N: 0. 16-0.38 g/L) , positive antiphospholipid antibodies IgM (48 MPL: N< 15,5 MPL), but negative in subsequent evaluations (including anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-Β2 glycoprotein and lupus anticoagulant). VDRL, TPHA, HIV1, HIV2, as well as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (cANCA and pANCA) and cryoglobulins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence performed in normal skin from the deltoid region showed nuclear epidermal deposition of IgG (Fig 3 ).

Treatment with oral methylprednisolone (24 mg/day) was initiated. Subjective symptoms progressively subsided and a rhinoscopy performed three months later showed resolution of the inflammatory signs without change of the size septum defect. Oral steroids were tapered until their suspension in September 2003. A few weeks later she presented symmetric small joint arthritis (mainly affecting both hands and less severely the elbows and knees) and photosensitivity. These were controlled with non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials and sun protective measures. Diffuse alopecia, myalgias and worsening of the joint complaints have been subsequently noticed.

After 18 months of followup the nasal symptoms remain controlled; no progression of the nasal septum defect was seen and remaining clinical and laboratory data are similar to those described above.

Discussion

LE can present with protean manifestations, and criteria to assist diagnosis have been established by the American Rheumatism Association [1, 2]. Our patient fulfills four of these criteria: oral ulcers (nasal septum perforation), photosensitivity, arthritis and serological alterations (positive antinuclear antibodies, with positive Ro/SS-A).

A few cases of LE with nasal septum perforation have been reported [3-11]. In a study performed in the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic (UTLC) [3], among 885 SLE patients seen between 1970 and 1998, where nasal septum perforation was prospectively looked for, it was found in forty cases (4.6 %). In a MEDLINE search we found 22 additional cases [4-11]. The relatively high percentage of nasal septum perforation in the UTLC study could, in part, be attributed to its prospective nature, and suggests that this feature can be underestimated in LE. The average age of detection of nasal septum perforation in UTLC study was 42 years, and mean SLE duration 6.1 years. The lesion was solitary and, in all but one case, there was significant LE activity, often with evidence of systemic vasculitis. In the majority of cases, the patients had other mucosal ulcerations, mostly oral, preceding the nasal septum perforation. These data are similar to those reported in the additional described cases [4-11].

The defect is located at the anterior and inferior cartilaginous nasal septum [3-11]. Nasal mucosa may be diffusely erythematous, edematous, or atrophic. Epistaxis, crusting, foul smell and mucopurulent discharge often accompany the defect. Epistaxis, in general minor, are frequently an early symptom, as in the present case. As a rule the lesion is asymptomatic [4, 6-11], and often the patients are not aware of their nasal problem [11], which would contribute to the underdiagnosis of nasal perforation in LE. Less frequently, as in our patient, it can be painful and tender [5].

No association between nasal septum perforation and a particular symptom or laboratory alteration of LE could be found in the reported cases. It appears that the septum perforation, although generally accompanying disease activity, is not a pejorative sign in LE [3]. However, its significance in the disease remains to be established.

It is thought that the defect begins as a nasal mucosal ulceration, secondary to ischemia with subsequent chondrolysis [4, 7, 11]. The high prevalence of systemic vasculitis in LE patients showing nasal septum perforation led to the suggestion that vasculitis could be an important etiologic feature [3]. However, as in the present case, no histological evidence of vasculitis has been documented in the nasal mucosa of LE patients with nasal septum perforation. Although direct immunofluorescence of perilesional nasal mucosa was not performed in our case, no positive pattern was seen in the cases where it was done [7, 9, 11]. In our patient circulating immune complexes and hypocomplementemia were present, but no evidence of cutaneous or visceral vasculitis was found. Increased blood viscosity and Raynaud phenomenon have also been pointed as causes of the perforation [7, 9]. Primary chondrolysis is thought to be unlikely since in LE cartilage destruction is limited [7].

Therapy should be directed, as in our case, to control epistaxis or the inflammatory nasal symptoms [7, 11]. Oral corticosteroids are the treatment of choice [7, 11]. Antimalarials alone are also claimed to control the symptoms [7]. Thalidomide was not considered in our patient as she presented transitory elevation of anti-phospholipid antibodies, and in this context thrombosis may supervene [1, 2].

Although a recognized feature of LE, nasal septum perforation rarely constitutes the presenting sign. We found 2 cases of LE where this occurred [3]. In these, nasal septum perforation was accompanied by other, more classic, symptoms of L E [3]. The case we present seems peculiar in that the nasal septum perforation occurred as the sole manifestation of LE during a period of two years and emphasizes the importance of this not well known feature in the diagnosis of this disease.

References

1. Saurat JH, Musette P. Signes cutanés du lupus érythémateux. In: Saurat JH, Grosshans E, Laugier P, Lachapelle JM, (eds). Dermatologie et Maladies Sexuellement Transmissibles, 3e ed. Masson, Paris, 1999: 313-322.2. Sontheimer RD. Lupus Erythematosus. In: Freedberg IN, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Fitzpatrick TB, (eds). Dermatology in General Medicine, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill, USA, 1999: 1993-2009.

3. Rahmam P, Gladman D, Urowitz M. Nasal septum perforation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus - Time for a closer look. J. Rheumathol. 1999; 26: 1854-1855.

4. Alcala H, Segovia DA. Ulceration and perforation of the nasal septum in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med .1969; 281: 722-723.

5. Vachtenheim J, Grossmann J. Perforation of the nasal septum in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Br. Med. J. 1969; 2: 98.

6. Simpson J. Nasal-septum perforation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med .1974; 290: 859-860.

7. Snyder G, McCarthy R, Toomey J, Rothfield N. Nasal septum perforation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arch. Otolaryngol .1974; 99: 456-457.

8. Rothfield N. Nasal-septum perforation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1974; 291: 51.

9. Willkens R, Roth G, Novak A, Walike J. Perforation of nasal septum in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis. Rheum. 1976; 19: 119-121.

10. Lerner D. Nasal septum perforation and carotid cavernous aneurysm: unusual manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1996; 115: 163-166.

11. Reiter D., Myers A.R. Asymptomatic nasal septum perforation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Otol. 1980; 89: 78-80.

12. Flagueil B, Wallach D, Cavellier-Balloy B, Bachelez H, Carzsuzaa F, Dubertret L. Thalidomide et thromboses. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2000; 127: 171-174.

© 2005 Dermatology Online Journal